Preparing for the CFA Exam requires a thorough understanding of Fixed-Income Instrument Features, a core component of the Fixed-Income syllabus. Mastery of bond structures, interest payments, and embedded options is essential. This knowledge provides insights into bond valuation, risk assessment, and market dynamics, critical for achieving a high CFA score.

Learning Objective

In studying "Fixed-Income Instrument Features" for the CFA Exam, you should develop a comprehensive understanding of the key characteristics of various fixed-income securities, including bonds, notes, and asset-backed securities. Examine the structural features such as coupon rates, maturities, and yield conventions, and understand how embedded options like call and put provisions impact investor returns and risks. Evaluate the role of credit ratings, seniority, and collateral in influencing a security’s risk profile. Additionally, explore how these features contribute to pricing and market demand in different economic conditions, and apply this understanding to analyze bond portfolios and investment strategies in CFA exam scenarios.

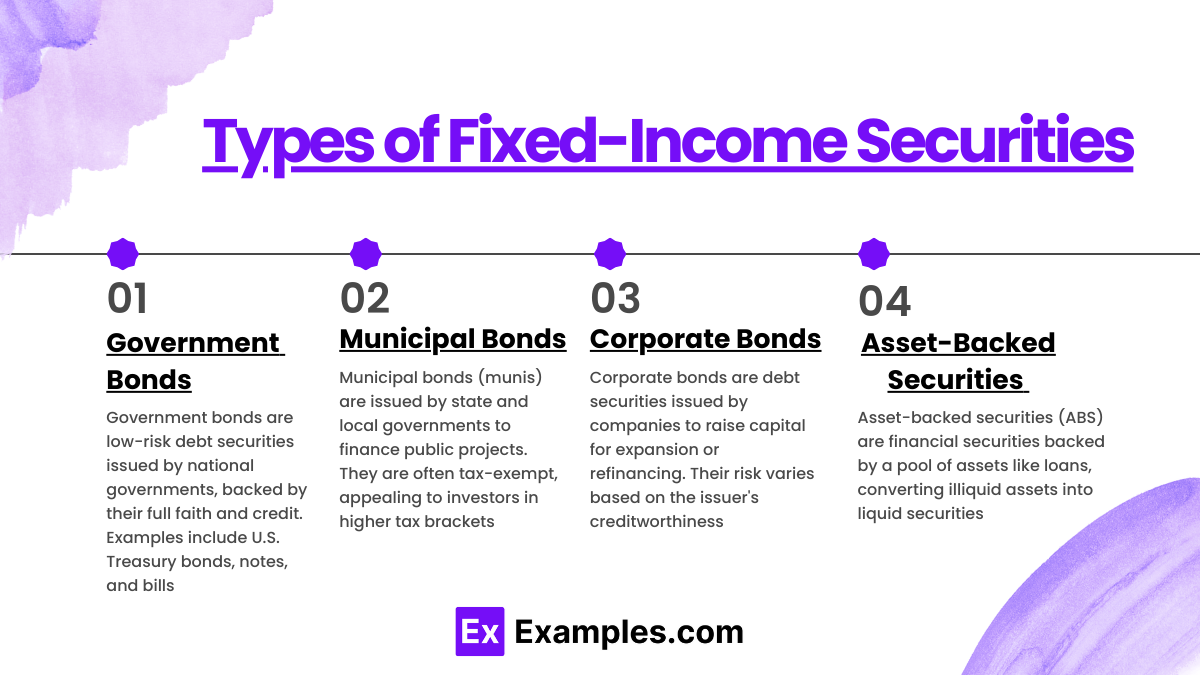

Types of Fixed-Income Securities

Fixed-income securities represent a class of investments that provide returns in the form of regular, fixed payments and the eventual return of principal at maturity. Understanding the various types of fixed-income securities is essential for CFA candidates as these instruments play a crucial role in investment portfolios and market dynamics. Below are the primary categories of fixed-income securities:

1. Government Bonds

Government bonds are debt securities issued by national governments. They are typically seen as low-risk investments because they are backed by the full faith and credit of the issuing government. In the U.S., Treasury bonds, notes, and bills are common examples.

Treasury Bonds: Long-term securities with maturities ranging from 10 to 30 years, offering fixed interest payments (coupons) every six months.

Treasury Notes: Medium-term securities with maturities ranging from 2 to 10 years, also offering semi-annual coupon payments.

Treasury Bills: Short-term securities maturing in one year or less, sold at a discount to face value, with no coupon payments; the return is the difference between the purchase price and the face value at maturity.

2. Municipal Bonds

Municipal bonds (or "munis") are issued by state and local governments to finance public projects like schools, highways, and hospitals. They are often tax-exempt at the federal level and sometimes at the state and local levels, making them attractive to investors in higher tax brackets.

General Obligation Bonds: These bonds are secured by the full faith and credit of the issuing municipality, relying on the government's taxing power to pay bondholders.

Revenue Bonds: These are backed by specific revenue sources, such as tolls from a toll road or fees from a public utility, rather than the issuer’s general taxing power.

3. Corporate Bonds

Corporate bonds are debt securities issued by companies to raise capital for various purposes, including expanding operations or refinancing existing debt. The risk associated with corporate bonds varies significantly based on the issuing company's creditworthiness.

Investment-Grade Bonds: These bonds are rated BBB or higher by credit rating agencies and are considered to have a lower risk of default.

High-Yield Bonds (Junk Bonds): Bonds rated below BBB are categorized as high-yield, reflecting a higher risk of default but offering higher potential returns to compensate for that risk.

4. Asset-Backed Securities (ABS)

Asset-backed securities are financial securities backed by a pool of underlying assets, such as loans, leases, credit card debt, or receivables. ABS allow issuers to convert illiquid assets into liquid securities, providing investors with diversified cash flows.

Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS): A specific type of ABS backed by mortgage loans. MBS can be further classified into agency MBS (backed by government-sponsored enterprises) and non-agency MBS (backed by private entities).

Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs): These are complex securities backed by a diversified pool of loans, including corporate bonds, mortgages, and other ABS. CDOs are structured in tranches, allowing for different risk and return profiles.

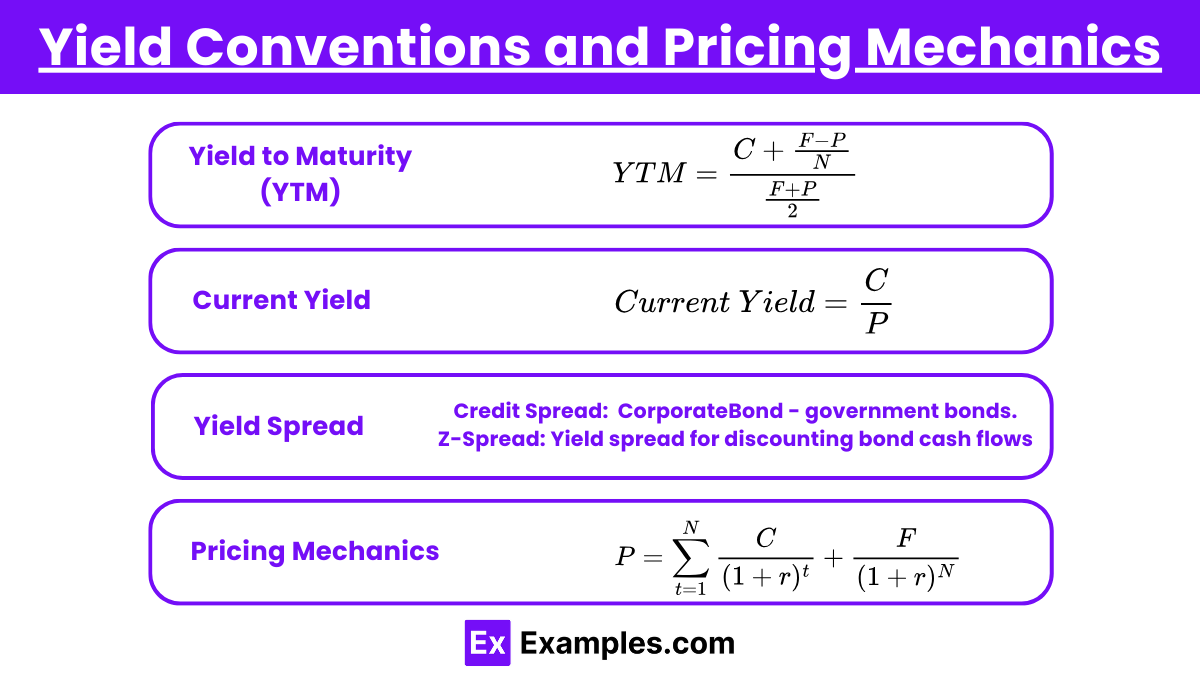

Yield Conventions and Pricing Mechanics

In the fixed-income market, understanding yield conventions and pricing mechanics is essential for evaluating bond investments and making informed decisions. Yield measures reflect the returns an investor can expect from a bond, while pricing mechanics help determine the current market value of these securities.

Yield to Maturity (YTM)

Yield to maturity is the most comprehensive measure of a bond's return, representing the total return an investor can expect if the bond is held until maturity. YTM considers all future cash flows, including:

Coupon Payments: Regular interest payments received by the investor.

Face Value: The principal amount returned at maturity.

Purchase Price: The price paid for the bond, which may differ from its face value.

The YTM is calculated using the following formula:

Where:

C = annual coupon payment

F = face value of the bond

P = current market price of the bond

N = number of years to maturity

Current Yield

Current yield is a simpler measure of a bond's income return, calculated by dividing the annual coupon payment by the bond's current market price. This metric provides a snapshot of the income generated by the bond relative to its market value:

Where:

C = annual coupon payment

P = current market price of the bond

Current yield is useful for investors seeking immediate income but does not account for capital gains or losses from holding the bond until maturity.

Yield Spread

Yield spread refers to the difference between the yields of two different fixed-income securities, often used to compare the risk and return profiles of bonds with similar maturities but different credit qualities. Common types of yield spreads include:

Credit Spread: The difference in yield between a corporate bond and a government bond of similar maturity, reflecting the additional risk associated with corporate bonds.

Z-Spread: A measure of the yield spread that accounts for the entire yield curve, representing the constant spread that would need to be added to the risk-free rate to discount a bond's cash flows to its current market price.

Pricing Mechanics

Bond pricing is influenced by several factors, including interest rates, credit quality, and market conditions. The relationship between a bond's price and its yield is inverse: when interest rates rise, bond prices fall, and vice versa. Key pricing concepts include:

Present Value of Cash Flows: The price of a bond is the present value of its expected future cash flows, which includes all coupon payments and the face value at maturity. Investors discount these cash flows at the prevailing market interest rate to determine the bond's price.

Discounting Cash Flows: The formula for calculating the present value of a bond's cash flows is:

Where:

P = current market price of the bond

C = annual coupon payment

F = face value of the bond

r = market interest rate (yield to maturity)

N = number of years to maturity

Clean Price vs. Dirty Price: The clean price of a bond excludes accrued interest, while the dirty price includes it. The dirty price reflects the total amount an investor pays for a bond, including any interest that has accrued since the last coupon payment.

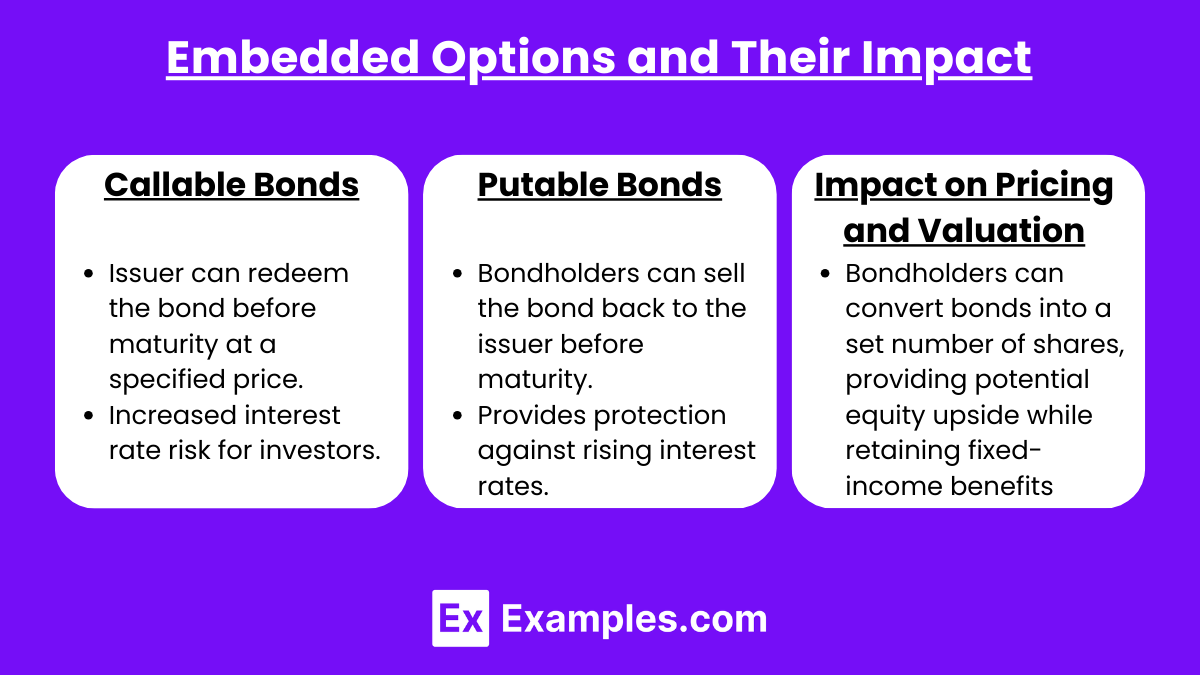

Embedded Options and Their Impact

Callable Bonds

Issuer can redeem the bond before maturity at a specified price.

Increased interest rate risk for investors.

Putable Bonds

Bondholders can sell the bond back to the issuer before maturity.

Provides protection against rising interest rates.

Impact on Pricing and Valuation

Bondholders can convert bonds into a predetermined number of shares.

Offers potential equity upside alongside fixed-income characteristics.

Credit Ratings and Credit Risk

Credit Ratings

Assess the creditworthiness of bond issuers, indicating their ability to meet financial obligations.

Ratings are assigned by credit rating agencies (e.g., Moody's, Standard & Poor's, Fitch).

Ratings scale:

Investment-Grade Ratings: BBB- or higher, indicating low credit risk.

High-Yield Ratings (Junk Bonds): BB+ or lower, indicating higher credit risk and potential for default.

Credit Risk

The risk that a bond issuer will default on its payments of interest or principal.

Influences the yield offered on a bond; higher credit risk typically results in higher yields.

Factors affecting credit risk include:

Issuer Financial Health: Analysis of income statements, balance sheets, and cash flow statements.

Industry and Economic Conditions: Economic downturns can impact issuer performance and creditworthiness.

Debt Levels: Higher levels of debt relative to equity can increase credit risk.

Impact on Investment Decisions

Investors use credit ratings to assess risk and make informed investment choices.

Portfolio management strategies may adjust based on the credit quality of bonds.

Diversification can mitigate credit risk by spreading investments across different issuers and sectors.

Monitoring Credit Risk

Continuous assessment of issuer creditworthiness through financial news, earnings reports, and changes in credit ratings.

Use of credit default swaps (CDS) to hedge against potential defaults.

Market Demand and Economic Sensitivity

Market Demand

The demand for fixed-income securities is influenced by interest rates, economic conditions, and investor sentiment.

Interest Rate Impact: As interest rates rise, the demand for existing bonds typically falls since new bonds are issued at higher rates.

Flight to Quality: During economic uncertainty, investors may shift their preferences towards safer fixed-income securities, such as government bonds, increasing their demand.

Economic Sensitivity

Fixed-income securities are sensitive to changes in economic conditions, including inflation, unemployment rates, and overall economic growth.

Interest Rate Risk: Bonds are particularly sensitive to interest rate changes; rising rates can decrease bond prices, impacting investor returns.

Credit Risk During Recession: Economic downturns can lead to increased default rates, particularly for lower-rated bonds, affecting their demand and pricing.

Yield Curve Dynamics: The shape of the yield curve (normal, inverted, or flat) reflects investor expectations about future economic conditions and influences demand for different maturities of bonds

Examples

Example 1: Treasury Bonds

Treasury bonds are long-term fixed-income securities issued by the U.S. government with maturities ranging from 10 to 30 years. They offer fixed coupon payments every six months and are considered one of the safest investments due to being backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government. Their predictable cash flows and low credit risk make them attractive to conservative investors.

Example 2: Corporate Bonds

Corporate bonds are issued by companies to raise capital for various purposes. They typically offer higher yields than government bonds due to increased credit risk. Corporate bonds can be categorized as investment-grade (lower risk) or high-yield (higher risk), impacting their pricing, yield, and demand in the market. Investors assess a company’s financial health to determine the risk associated with these bonds.

Example 3: Municipal Bonds

Municipal bonds are debt securities issued by state and local governments to finance public projects. They are often exempt from federal taxes and sometimes state and local taxes, making them particularly attractive to investors in higher tax brackets. There are two main types: general obligation bonds, which are backed by the issuer's credit and taxing power, and revenue bonds, which are backed by specific revenue sources.

Example 4: Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS)

Mortgage-backed securities are a type of asset-backed security secured by a pool of mortgage loans. Investors receive periodic payments derived from the mortgage payments made by homeowners. MBS can offer attractive yields, but they also carry risks associated with prepayment (when borrowers pay off their loans early) and changes in interest rates, which can affect the cash flows to investors.

Example 5: Convertible Bonds

Convertible bonds are hybrid securities that allow bondholders to convert their bonds into a predetermined number of shares of the issuing company's stock. This feature provides potential for equity upside if the company performs well. Convertible bonds typically have lower coupon rates than traditional bonds due to the added value of the conversion option, appealing to investors seeking both fixed income and equity exposure

Practice Questions

Question 1

What is the primary advantage of investing in callable bonds for issuers?

A) They provide investors with guaranteed returns.

B) They allow issuers to refinance debt if interest rates decline.

C) They increase the overall credit rating of the issuer.

D) They require higher interest payments than non-callable bonds.

Correct Answer: B

Explanation: Callable bonds give issuers the option to redeem the bonds before maturity, typically when interest rates decline. This allows issuers to refinance their debt at lower rates, reducing interest expenses.

Question 2

Which of the following statements accurately describes municipal bonds?

A) They are issued exclusively by the federal government.

B) Interest earned is typically subject to federal income tax.

C) They can provide tax-exempt income to investors in certain cases.

D) They generally have higher yields than corporate bonds.

Correct Answer: C

Explanation: Municipal bonds are often exempt from federal income tax and sometimes state and local taxes, making them attractive to investors in higher tax brackets. This tax-exempt status can provide significant savings compared to taxable bonds.

Question 3

In the context of fixed-income securities, what does the term "seniority" refer to?

A) The maturity date of the bond.

B) The interest rate paid on the bond.

C) The order of claims on a company's assets in the event of liquidation.

D) The tax treatment of the bond’s interest payments.

Correct Answer: C

Explanation: Seniority in fixed-income securities refers to the hierarchy of claims on a company's assets during liquidation. Senior debt holders have the first claim on assets, followed by subordinated debt holders, impacting their risk and potential recovery in the event of default.