Portfolio Risk and Performance Attribution focuses on identifying and quantifying the sources of risk and return within a portfolio, allowing managers to understand the impact of their investment decisions. This analysis involves measuring both systematic and unsystematic risks, as well as examining the contributions from asset allocation, security selection, and other factors. By assessing these elements, portfolio managers can enhance decision-making, optimize performance, and communicate results effectively to clients, ensuring alignment with investment objectives and improving risk-adjusted returns for consistent portfolio growth.

Learning Objectives

In studying "Portfolio Risk and Performance Attribution" for the CMT Exam, you should learn to understand the techniques for measuring and analyzing risk within a portfolio, including systematic and unsystematic risk, beta, Value at Risk (VaR), and tracking error. Evaluate methods for performance attribution, such as asset allocation, security selection, and interaction effects, to identify factors driving portfolio returns. Analyze tools like the Brinson model and multi-factor models for attributing performance to specific decisions. Additionally, explore how these risk assessment and attribution techniques support strategic portfolio adjustments, enhance client communication, and improve risk management across various market conditions.

Portfolio risk and performance attribution involve identifying and quantifying sources of risk and return in a portfolio. By understanding how specific factors contribute to overall performance, portfolio managers can better adjust their strategies, align portfolios with investment objectives, and enhance performance. Risk assessment tools and performance attribution models are used to analyze both systematic and idiosyncratic risks, which helps in refining portfolio construction and improving decision-making.

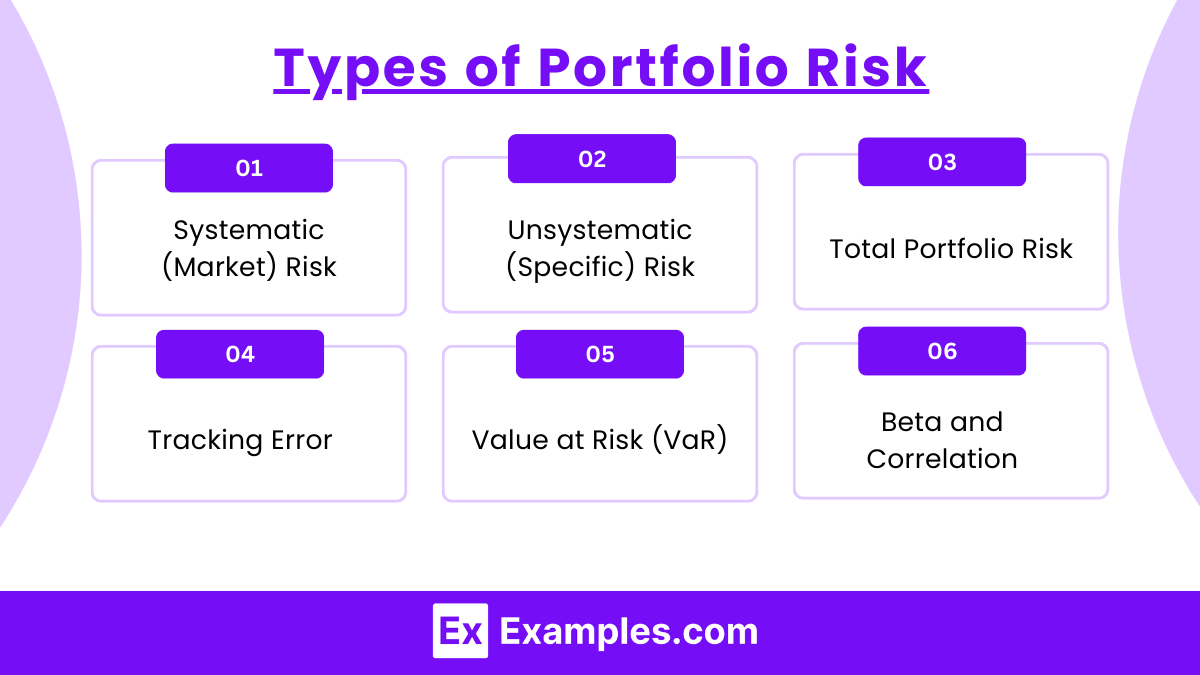

Types of Portfolio Risk

Systematic (Market) Risk:

Systematic risk is the inherent risk associated with the entire market or a particular market segment. Factors such as economic recessions, political instability, inflation, or global events drive systematic risk.

Since systematic risk affects all assets in the market, it cannot be eliminated through diversification. Examples include interest rate risk, inflation risk, and market volatility.

Unsystematic (Specific) Risk:

Unsystematic risk is associated with individual assets or sectors, influenced by company-specific or industry-specific factors. Examples include business risk, financial risk, or operational issues.

Diversification can reduce unsystematic risk by spreading investments across different assets, sectors, or geographies.

Total Portfolio Risk:

Total risk in a portfolio includes both systematic and unsystematic risk. It is typically measured using standard deviation, which captures the overall variability of portfolio returns.

Tracking Error:

Tracking error measures the deviation of a portfolio’s returns from its benchmark. It is especially important for active managers who seek to outperform a benchmark.

High tracking error may indicate a more aggressive approach, while low tracking error implies closer alignment with the benchmark.

Value at Risk (VaR):

VaR estimates the potential loss in a portfolio over a specified time frame, given normal market conditions and a confidence interval.

It is widely used for risk management, providing a threshold of potential loss that helps managers determine the risk exposure of their portfolio.

Beta and Correlation:

Beta measures the portfolio’s sensitivity to market movements, indicating its volatility relative to the market. A high-beta portfolio is more volatile, while a low-beta portfolio is more stable.

Correlation measures the relationship between assets in a portfolio, essential for diversification. Low or negative correlation between assets can reduce overall portfolio risk.

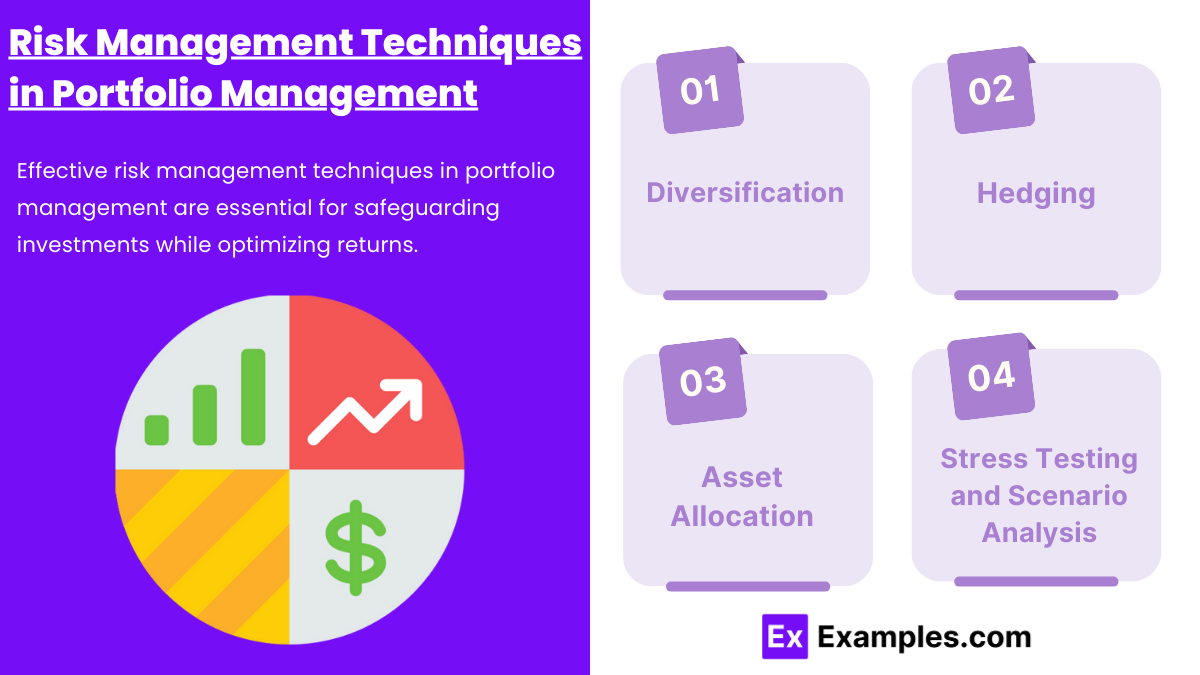

Risk Management Techniques in Portfolio Management

Diversification:

Diversifying across different asset classes, sectors, or geographies can reduce unsystematic risk and lower overall portfolio volatility.

Strategic and tactical diversification allow managers to spread risk while potentially enhancing returns.

Hedging:

Hedging strategies, including options, futures, and other derivatives, protect against downside risk. These instruments can help manage exposure to currency, interest rate, and commodity risks.

Portfolio managers may use long/short positions, protective puts, or covered calls to limit potential losses.

Asset Allocation:

Asset allocation decisions are fundamental to risk management. By determining the proportion of various asset classes (equities, bonds, cash, alternatives), managers align portfolios with risk tolerance and investment goals.

Adjusting asset allocation based on market conditions can help balance risk and reward over time.

Stress Testing and Scenario Analysis:

Stress testing evaluates how a portfolio would perform under adverse market conditions, such as economic downturns or financial crises.

Scenario analysis allows managers to assess the impact of hypothetical events, such as interest rate changes or geopolitical crises, on portfolio performance.

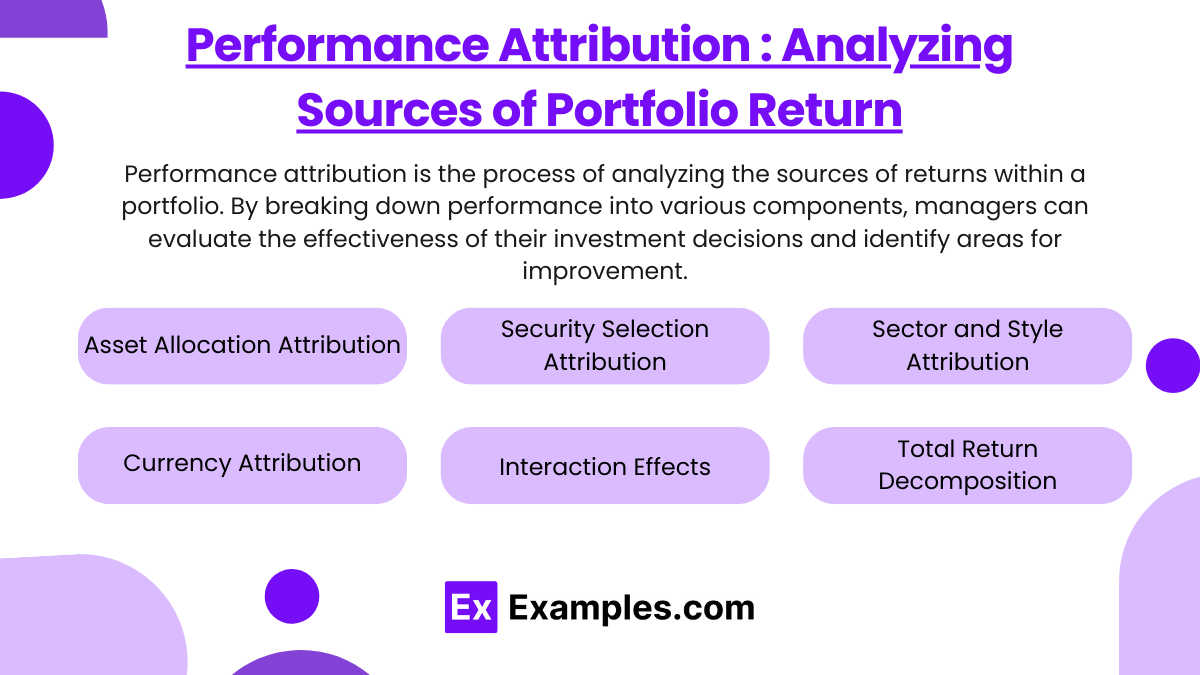

Analyzing Sources of Portfolio Return

Performance attribution is the process of analyzing the sources of returns within a portfolio. By breaking down performance into various components, managers can evaluate the effectiveness of their investment decisions and identify areas for improvement.

Asset Allocation Attribution:

This assesses the contribution of asset allocation decisions to the portfolio’s overall return. For example, a manager’s decision to overweight equities in a bull market may positively contribute to performance.

Asset allocation attribution examines how well managers’ allocations align with the market environment.

Security Selection Attribution:

Security selection attribution evaluates the impact of individual security choices on portfolio performance, separate from asset allocation.

For instance, selecting high-performing stocks within an underperforming sector can reflect the manager’s skill in identifying superior investments.

Sector and Style Attribution:

Sector attribution isolates the performance contributions of different sectors within the portfolio, enabling analysis of specific industry exposure.

Style attribution examines the performance impact of investment style choices, such as growth vs. value or small-cap vs. large-cap stocks.

Currency Attribution:

For global portfolios, currency fluctuations can significantly impact performance. Currency attribution analyzes the gains or losses resulting from changes in foreign exchange rates.

Managers may use currency hedging to minimize currency risk in international portfolios.

Interaction Effects:

Interaction effects reflect the combined impact of asset allocation and security selection decisions. This effect is often a residual component in attribution analysis, highlighting the complex interplay between different factors in the portfolio.

Total Return Decomposition:

The total return decomposition separates a portfolio’s return into key components, including benchmark return, active return, and alpha (the portion of return attributed to active management).

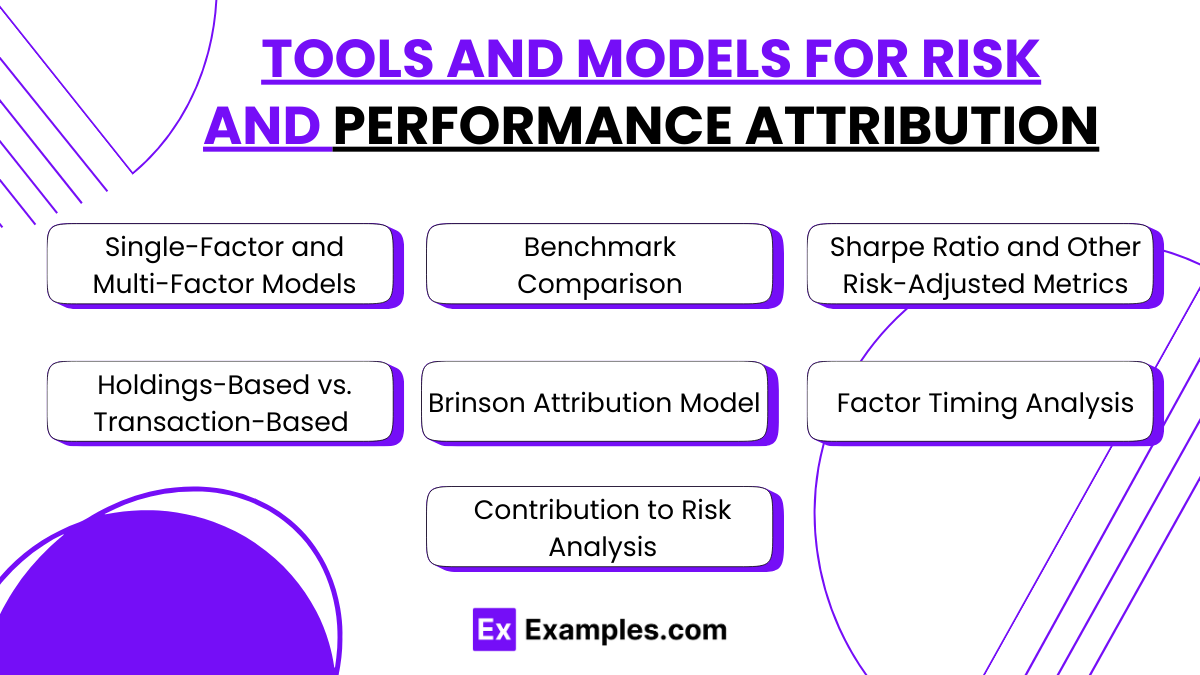

Tools and Models for Risk and Performance Attribution

Single-Factor and Multi-Factor Models:

Single-factor models, such as the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), focus on market risk (beta) as the primary driver of returns.

Multi-factor models, such as the Fama-French Three-Factor Model, incorporate additional risk factors like size and value, providing a more comprehensive attribution analysis.

Benchmark Comparison:

Comparing portfolio returns to a relevant benchmark provides a baseline for attribution. Performance relative to the benchmark reveals whether active management has added value.

Active return (portfolio return minus benchmark return) quantifies the effectiveness of the manager’s investment decisions.

Sharpe Ratio and Other Risk-Adjusted Metrics:

Risk-adjusted metrics such as the Sharpe Ratio, Information Ratio, and Sortino Ratio evaluate returns relative to the level of risk taken.

These metrics help in comparing portfolios with different risk profiles and determining if a manager’s strategy has generated excess returns.

Holdings-Based vs. Transaction-Based :

Holdings-based attribution uses the portfolio’s positions at the beginning of a period to assess performance, focusing on long-term allocations.

Transaction-based attribution considers the impact of specific trades, providing insights into the timing and effect of active decisions.

Brinson Attribution Model:

The Brinson model separates total return into allocation and selection effects. It evaluates the impact of decisions to overweight or underweight asset classes relative to the benchmark.

This model is widely used in equity attribution, offering a clear breakdown of asset allocation and selection contributions.

Factor Timing Analysis:

Factor timing analysis evaluates the impact of timing exposure to specific factors, such as market, size, value, or momentum, based on changing economic or market conditions.

By assessing how well a portfolio manager adjusts factor exposure over time, this analysis provides insight into the manager’s skill in capturing opportunities tied to economic cycles and market trends, offering an added dimension to attribution analysis.

Contribution to Risk Analysis:

Contribution to risk analysis identifies which assets or factors contribute most significantly to a portfolio’s overall risk. By decomposing total risk into individual components, managers can understand which positions drive volatility and potential losses.

This approach helps in refining portfolio structure and managing concentration risk, enhancing the portfolio’s risk-return profile.

Examples

Example 1: Evaluating Sector Allocation Impact on Performance

Suppose a portfolio manager overweights the technology sector in an equity portfolio during a period of strong tech sector performance. After reviewing the portfolio's performance attribution, the manager finds that this sector allocation decision contributed significantly to the portfolio’s excess return relative to the benchmark. This example illustrates the importance of sector allocation decisions, as choosing to overweight certain sectors in favorable conditions can enhance portfolio returns, while a different sector allocation could have led to underperformance.

Example 2: Measuring Security Selection Effectiveness in Fixed Income

A portfolio manager of a bond fund selects bonds with slightly lower credit ratings but higher yields, anticipating improved creditworthiness for these issuers. Over the performance period, attribution analysis reveals that these bond selections contributed to a higher return than the benchmark, thanks to both favorable credit upgrades and yield gains. This example demonstrates the importance of security selection attribution, where bond choice (rather than overall bond market performance) was a key factor driving excess return.

Example 3: Impact of Currency Attribution in a Global Portfolio

In an international equity portfolio, the manager decides not to hedge currency risk for investments in European markets. During a period of U.S. dollar depreciation relative to the Euro, the portfolio benefits from currency gains as the value of Euro-denominated assets increases when converted back to U.S. dollars. Currency attribution analysis shows that currency movements accounted for a significant portion of the portfolio’s outperformance. This example highlights how currency decisions can meaningfully impact portfolio returns in a global portfolio, where foreign exchange risk can be a source of both risk and return.

Example 4: Using Tracking Error to Assess Active Management

\A manager runs an actively managed fund with a stated goal of outperforming a benchmark index. By analyzing the portfolio’s tracking error (the difference in return volatility between the portfolio and the benchmark), the manager finds a higher-than-expected tracking error, indicating substantial deviations from the benchmark holdings. This analysis helps the manager understand that the portfolio’s active management strategy is resulting in greater risk, which may or may not be compensated by higher returns. This example shows how tracking error serves as an essential tool for managers to monitor the degree of active risk and assess the alignment with investment objectives.

Example 5: Stress Testing for Downside Risk Management

A portfolio manager anticipates potential market volatility due to upcoming economic announcements and conducts stress testing to gauge how a portfolio of high-yield corporate bonds would perform in a hypothetical recession scenario. The stress test reveals that the portfolio would experience significant drawdowns due to higher credit risk in economic downturns. Based on this insight, the manager adjusts the asset allocation, reducing exposure to high-yield bonds and reallocating to investment-grade bonds to mitigate potential losses. This example illustrates the value of stress testing as a risk management tool, allowing managers to proactively identify vulnerabilities and adjust portfolios to reduce downside risk.

Practice Questions

Question 1

Which of the following best describes systematic risk in a portfolio?

A) Risk associated with individual asset choices within the portfolio

B) Risk that can be eliminated through diversification

C) Risk affecting the entire market or a specific market segment

D) Risk related to the portfolio manager’s security selection decisions

Answer: C) Risk affecting the entire market or a specific market segment

Explanation: Systematic risk, also known as market risk, refers to the risk that impacts the entire market or a broad segment of the market. This type of risk arises from macroeconomic factors such as economic recessions, political instability, inflation, or interest rate changes. Because it affects the whole market, systematic risk cannot be mitigated through diversification; instead, it’s inherent to all assets in a given market. Therefore, options like A and D, which refer to risks specific to individual assets or selection decisions, are incorrect. Option B is also incorrect because systematic risk cannot be diversified away—it’s the unsystematic risk that can be mitigated through diversification.

Question 2

Performance attribution is used in portfolio management to:

A) Measure the overall risk level in a portfolio

B) Quantify the impact of individual asset selection and allocation decisions on portfolio returns

C) Determine the potential losses in a portfolio over a specific period

D) Reduce both systematic and unsystematic risks

Answer: B) Quantify the impact of individual asset selection and allocation decisions on portfolio returns

Explanation: Performance attribution analyzes the sources of returns within a portfolio, allowing portfolio managers to identify the impact of their asset allocation and security selection decisions. By breaking down returns into components, such as asset allocation effects and security selection effects, performance attribution enables managers to assess how each decision contributed to overall performance. This is a key tool in evaluating whether active management decisions added value relative to a benchmark. Option A is incorrect, as performance attribution focuses on returns, not risk levels. Option C refers to risk management (such as through VaR), and option D does not accurately describe the purpose of performance attribution, which is about return analysis, not risk reduction.

Question 3

In the Brinson attribution model, what are the two primary components of performance attribution?

A) Allocation and beta

B) Selection and interaction

C) Allocation and selection

D) Risk and return

Answer: C) Allocation and selection

Explanation: The Brinson attribution model breaks down a portfolio’s performance relative to a benchmark into two primary components: allocation effect and selection effect. The allocation effect measures the impact of the manager’s decision to overweight or underweight specific asset classes or sectors compared to the benchmark, while the selection effect measures the impact of choosing individual securities within those classes or sectors. Together, these components allow portfolio managers to see whether their strategic and tactical decisions in asset allocation and security selection contributed positively or negatively to performance. Options A and B include terms not directly associated with the Brinson model in this context. Option D is too general, as risk and return are broader concepts not specific to the Brinson attribution model.