Preparing for the MBE Exam requires a thorough understanding of contract content and meaning, a core component of contract law. Mastery of contract terms, interpretation principles, conditions, and covenants is essential. This knowledge clarifies the rights, duties, and obligations of parties, critical for resolving disputes and achieving a high MBE score.

Learning Objective

In studying “Contract Content and Meaning” for the MBE Exam, you should learn to interpret the terms and provisions that define contract obligations and rights. Analyze the principles of contract interpretation, including the plain meaning rule, contextual interpretation, and usage of trade. Evaluate conditions precedent, subsequent, and concurrent, as well as the impact of warranties, representations, and covenants. Understand how ambiguity is resolved through rules of construction and the role of parol evidence. Additionally, explore how courts enforce, modify, or interpret these terms in disputes, and apply your understanding to MBE practice questions for effective legal analysis.

Principles of Contract Interpretation

The principles of contract interpretation guide courts in determining the meaning and intent behind the language and terms of a contract. Understanding these principles is essential for interpreting and enforcing agreements accurately. The goal of contract interpretation is to discern the parties’ intent and uphold the terms they agreed to in a fair and consistent manner. Below are key principles used in the interpretation of contracts.

1. Plain Meaning Rule

The plain meaning rule requires courts to interpret the words of a contract according to their ordinary and commonly understood meanings. This rule assumes that the parties have chosen their words deliberately and that the language of the contract accurately reflects their intentions. Courts generally refrain from altering or creating terms that do not appear within the contract unless ambiguity exists.

- Application: If a term is unambiguous, the court will enforce it as written without considering extrinsic evidence.

- Exceptions: If the contract’s language is unclear or ambiguous, courts may examine extrinsic evidence to determine the parties’ intent. Ambiguities are often resolved against the drafter of the contract (a principle known as “contra proferentem”).

2. Contextual Interpretation

Contextual interpretation considers the broader context of the contract to clarify ambiguous terms. This approach allows courts to look at factors surrounding the formation and execution of the contract, such as:

- Circumstances of the Contract: Courts may examine the context in which the contract was created, including the parties’ backgrounds, industry norms, and any relevant communications.

- Entire Contract Interpretation: Contracts are typically interpreted as a whole, with preference given to consistency and avoiding interpretations that render provisions contradictory or meaningless.

- Custom and Trade Usage: In some cases, courts consider the customs and practices within a particular trade or industry to resolve ambiguities in contract terms.

3. Usage of Trade, Course of Dealing, and Course of Performance

These concepts are commonly used in contract interpretation, particularly under the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC).

- Usage of Trade: This refers to practices or methods regularly observed in a particular industry. If a term in the contract has a customary meaning within the industry, courts may interpret it accordingly.

- Course of Dealing: Past conduct between the parties that establishes a common basis of understanding can clarify the meaning of contract terms. Courts may use prior dealings to interpret unclear provisions.

- Course of Performance: If a contract involves repeated performance and one party has consistently acted a certain way with the other party’s knowledge and without objection, this conduct may be used to interpret ambiguous terms.

4. Parol Evidence Rule and Ambiguities

- Parol Evidence Rule: This rule limits the use of external evidence to interpret or alter the terms of a written contract. When a written agreement is considered a complete and final expression of the parties’ agreement, evidence outside the contract (oral or written statements made prior to or contemporaneously with the contract) is generally inadmissible to contradict, vary, or add to its terms.

- Exceptions: There are important exceptions to the parol evidence rule. Courts may admit external evidence to clarify ambiguities, show that a term was omitted due to fraud or mistake, or address a partially integrated agreement (where the writing does not encompass the entire agreement).

- Resolving Ambiguities: When faced with ambiguous terms, courts apply rules of construction to determine the intent of the parties. For example, ambiguities may be interpreted against the drafter, handwritten terms may take precedence over preprinted terms, and specific terms may override general ones.

5. Rules of Construction

Courts use various rules of construction to interpret and give effect to contract terms:

- Interpret Contracts as a Whole: Courts aim to give effect to all provisions and avoid interpretations that render any part meaningless.

- Preference for Specific Over General: When specific terms conflict with general terms, the specific terms typically take precedence.

- Handwritten vs. Printed Terms: Handwritten terms may override conflicting preprinted or typed terms because they are presumed to reflect the parties’ most recent intentions.

- Contra Proferentem (Ambiguities Against the Drafter): Ambiguities in a contract are often interpreted against the party that drafted the agreement, especially when the drafting party is in a stronger bargaining position.

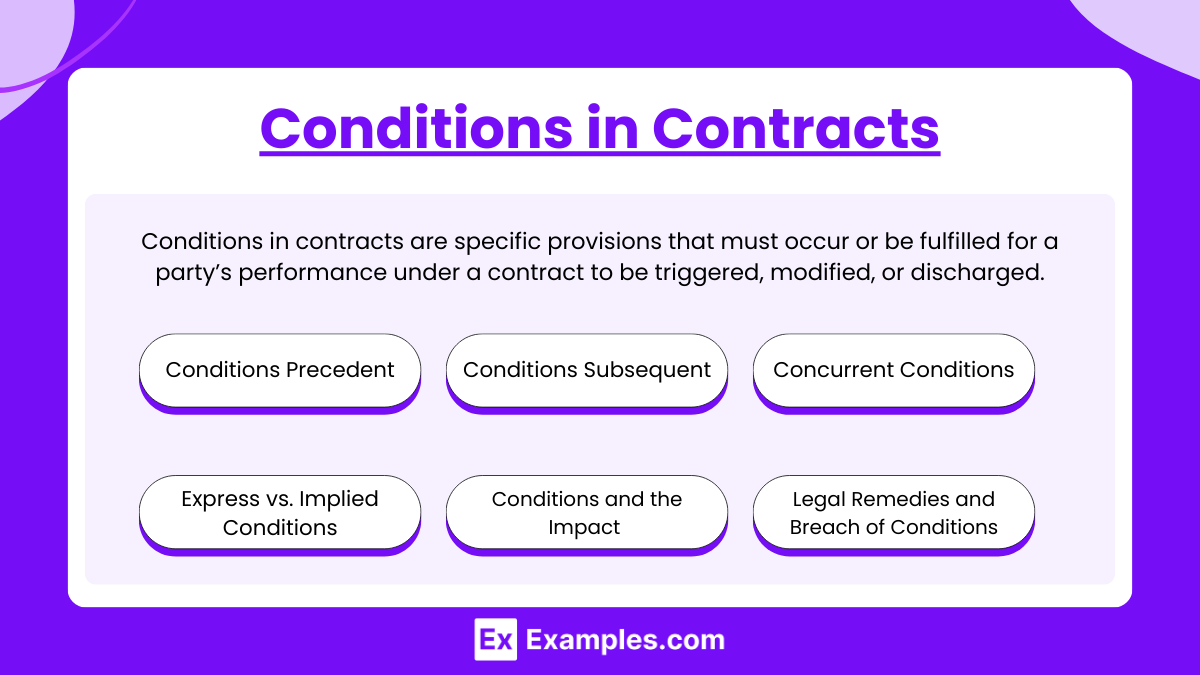

Conditions in Contracts

Conditions in contracts are specific provisions that must occur or be fulfilled for a party’s performance under a contract to be triggered, modified, or discharged. Conditions help define the rights and obligations of the parties, making them critical for determining the enforceability and execution of contractual duties. Understanding the different types of conditions is essential for interpreting and performing contracts. Below is a detailed explanation of key types of conditions and their significance.

1. Conditions Precedent

A condition precedent is an event or action that must occur before a party’s obligation to perform a contract arises. Essentially, it acts as a “trigger” for performance.

- Example: A seller may agree to sell goods to a buyer only if the buyer secures financing by a specific date. The seller’s obligation to deliver the goods is contingent on the buyer meeting this condition.

- Legal Significance: If a condition precedent is not met, the obligated party does not have to perform. Courts typically enforce such conditions strictly, provided they are clearly stated in the contract.

2. Conditions Subsequent

A condition subsequent is an event or action that, if it occurs, can terminate an existing contractual obligation. Unlike a condition precedent, which must occur for a duty to arise, a condition subsequent operates to end a duty that is already in effect.

- Example: An employee may continue receiving benefits under a contract unless a condition, such as failing to maintain a specific license, occurs. If the employee fails to meet the condition, the employer’s obligation to provide benefits ends.

- Legal Significance: When a condition subsequent is triggered, the party’s duty to perform is discharged. Courts may require clear language to establish that a condition subsequent applies to avoid unjust termination of duties.

3. Concurrent Conditions

Concurrent conditions are obligations that both parties must perform simultaneously for the contract to be executed. The duties of each party are dependent on the performance of the other, meaning that neither party is obligated to perform until the other party is ready, willing, and able to do so.

- Example: In a real estate transaction, the buyer’s obligation to pay and the seller’s obligation to transfer title typically occur at the same time. Each party’s performance is contingent on the other’s.

- Legal Significance: If one party fails to perform their obligation, the other party is typically relieved of their duty to perform. Courts may examine whether both parties acted in good faith to fulfill their obligations.

4. Express vs. Implied Conditions

- Express Conditions: These are explicitly stated in the contract, often using clear language such as “if,” “provided that,” “on condition that,” or “unless.” Express conditions must be strictly met for the related contractual duty to arise or be discharged.

- Example: A contract may state that payment is due “provided that” the contractor completes the work by a certain date.

- Implied Conditions: These are not expressly stated but are inferred from the nature of the contract, the parties’ intentions, or by law. Implied conditions are often necessary to achieve the contract’s purpose and ensure fairness.

- Example: In a service contract, there is often an implied condition that the service will be performed in a competent and workmanlike manner.

5. Conditions and the Impact on Contractual Obligations

- Strict Compliance: In most cases, conditions must be strictly complied with for the related obligation to arise or be terminated. A failure to meet a condition may result in the non-performance of contractual duties.

- Waiver of Conditions: Parties may waive certain conditions, either expressly or through their conduct, indicating a willingness to proceed without the condition being fulfilled. Once waived, the condition cannot typically be used to avoid performance.

- Excuse of Conditions: Courts may excuse the non-occurrence of a condition if it would lead to unjust outcomes or if one party wrongfully prevents the condition from being fulfilled.

6. Legal Remedies and Breach of Conditions

The breach of a condition in a contract can have serious consequences. If a condition precedent is not met, the contract may never become enforceable. Conversely, if a condition subsequent occurs, an existing obligation may be terminated. Courts may provide remedies such as rescission, damages, or other relief based on the nature of the breached condition.

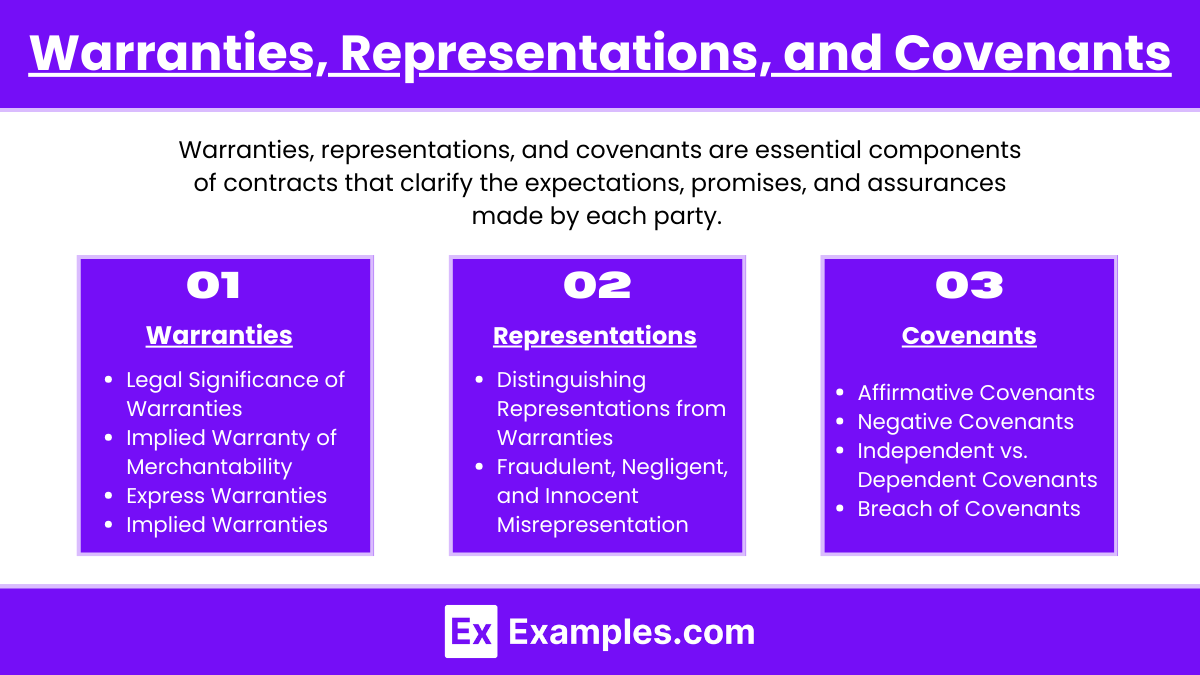

Warranties, Representations, and Covenants

Warranties, representations, and covenants are essential components of contracts that clarify the expectations, promises, and assurances made by each party. Each term serves a different function within the contract and can impact the rights, obligations, and remedies available to the parties. Understanding these terms helps ensure that parties accurately understand their commitments and can enforce them if necessary.

1. Warranties

A warranty is a promise or guarantee about certain facts or conditions related to the contract’s subject matter. Warranties are assurances by one party that certain statements or facts are true or that specific conditions will be met. If a warranty is breached, the other party may have the right to seek damages or other remedies.

- Express Warranties: These are specific promises explicitly stated within the contract. Express warranties can include guarantees about the quality, condition, or performance of goods or services.

- Example: In a sales contract, a seller may warrant that a car is free from defects and has never been in an accident. This express warranty provides the buyer with recourse if the car turns out to have hidden issues.

- Implied Warranties: These are not explicitly stated but are implied by law based on the nature of the transaction. Common implied warranties include:

- Implied Warranty of Merchantability: This warranty guarantees that goods sold by a merchant are fit for ordinary use.

- Implied Warranty of Fitness for a Particular Purpose: This warranty applies when a buyer relies on the seller’s expertise to select goods for a specific purpose, and the seller knows of that purpose.

- Legal Significance of Warranties: If a warranty is breached, the party relying on it may seek remedies such as damages or contract rescission. In some cases, the breach of a significant warranty can allow the buyer to reject the goods or cancel the contract entirely.

2. Representations

A representation is a factual statement made by one party to induce the other party to enter into the contract. Representations are typically statements about past or present facts, and if found to be false, they may result in remedies such as damages or rescission of the contract.

- Distinguishing Representations from Warranties: While a warranty is a promise that certain facts are true or will be true in the future, a representation is an assertion about a fact, often used to persuade the other party to agree to the contract. Representations do not guarantee performance or future events.

- Example: In a real estate transaction, the seller may represent that the property has no liens or encumbrances. If this representation is false, the buyer may have grounds to rescind the contract or seek damages.

- Fraudulent, Negligent, and Innocent Misrepresentation: If a representation is false, remedies depend on the nature of the misrepresentation:

- Fraudulent Misrepresentation: If a party knowingly makes a false representation with intent to deceive, the other party may have a claim for fraud and may seek damages or rescind the contract.

- Negligent Misrepresentation: If a party makes a false representation due to a lack of reasonable care, the harmed party may seek damages based on the negligence.

- Innocent Misrepresentation: If a false statement was made without knowledge of its falsity and without negligence, the remedy may be limited to rescission of the contract.

3. Covenants

A covenant is a promise within a contract that obligates one party to perform or refrain from performing a specific action. Covenants can be either affirmative (requiring action) or negative (requiring abstention). They define ongoing duties and responsibilities between the parties.

- Affirmative Covenants: These are promises to perform specific actions.

- Example: In a loan agreement, a borrower may covenant to maintain a certain debt-to-equity ratio to assure the lender of their financial stability.

- Negative Covenants: These are promises to refrain from certain actions.

- Example: A company may covenant not to take on additional debt without the lender’s consent. This covenant protects the lender’s interest by limiting the borrower’s financial risk-taking.

- Independent vs. Dependent Covenants: Independent covenants are standalone promises that do not rely on the performance of other promises. Dependent covenants are linked to other promises in the contract; failure to perform one may relieve the other party from performing.

- Breach of Covenants: If a party breaches a covenant, the non-breaching party may seek remedies, including damages or specific performance, depending on the nature and importance of the breached covenant. For material breaches, the non-breaching party may be able to terminate the contract.

4. Legal Implications and Remedies for Breach

- Remedies for Breach of Warranty: If a warranty is breached, the injured party may seek damages or rescind the contract if the breach significantly affects the contract’s purpose. For example, a buyer may seek repair, replacement, or compensation if goods fail to meet warranty standards.

- Remedies for False Representations: False representations, especially fraudulent ones, may entitle the aggrieved party to rescind the contract or seek damages. Courts take misrepresentation seriously, particularly when it leads to a party entering a contract based on inaccurate or misleading information.

- Remedies for Breach of Covenant: The non-breaching party may seek damages, injunctive relief, or specific performance if a covenant is breached. If a material covenant is breached, the contract may be terminated.

Examples

Example 1: Plain Meaning Rule in Contract Interpretation

Scenario: A contractor agrees to complete a building project “within 90 days” of the start date. The client argues that the contract implied flexibility, but the contractor insists the deadline is strictly 90 days.

Legal Point: The plain meaning rule applies here. Courts would interpret “within 90 days” according to its clear, ordinary meaning, requiring strict compliance. Unless ambiguities exist, external evidence would not be admitted to alter this term.

Example 2: Usage of Trade in Clarifying Ambiguous Terms

Scenario: A contract for the sale of “Grade A” coffee beans is disputed because the seller delivered beans that do not meet the buyer’s expectations. The term “Grade A” is not defined in the contract.

Legal Point: The court may consider usage of trade to determine the meaning of “Grade A” based on industry standards and practices. If the trade custom clarifies what constitutes “Grade A” beans, it will be used to resolve the ambiguity.

Example 3: Conditions Precedent in a Contract

Scenario: A real estate contract states that the buyer’s obligation to purchase the property is contingent upon obtaining financing approval within 30 days. The buyer fails to secure financing in that timeframe.

Legal Point: This is an example of a condition precedent. The buyer’s obligation to perform (purchase the property) does not arise unless and until financing is approved. Failure to satisfy the condition relieves the buyer of their obligation to complete the purchase.

Example 4: Parol Evidence Rule and Integration Clause

Scenario: Two parties sign a written agreement for the sale of goods, which contains an integration clause stating it is the “complete and final” agreement. The buyer claims there was an oral agreement for additional warranty terms not included in the written contract.

Legal Point: The Parol Evidence Rule generally prohibits the introduction of prior or contemporaneous oral agreements to modify the terms of a fully integrated written contract. The integration clause supports the exclusion of the oral terms unless an exception applies (e.g., fraud).

Example 5: Express Warranty vs. Representation

Scenario: A seller states that a machine is “capable of operating at 100 units per hour” in both a promotional brochure and the sales contract. The machine only operates at 70 units per hour.

Legal Point: The statement in the sales contract constitutes an express warranty, creating a binding obligation regarding the machine’s performance. The buyer may seek remedies for breach of warranty if the promise is not fulfilled. If the statement only appeared in marketing materials, it could be treated as a representation, subject to different remedies if false.

Practice Questions

Question 1

What is the primary purpose of the Parol Evidence Rule in contract law?

A) To ensure all terms of a contract are written in plain language

B) To prohibit the modification of a written contract by oral agreements made prior to or at the same time as the written contract

C) To require that all contracts must be in writing to be enforceable

D) To allow courts to consider any relevant evidence to interpret ambiguous terms

Answer: B) To prohibit the modification of a written contract by oral agreements made prior to or at the same time as the written contract

Explanation: The Parol Evidence Rule prevents parties from using external oral or written statements made before or at the time of the contract’s execution to alter, contradict, or add to the terms of a fully integrated written contract. This rule helps maintain the integrity of written agreements by treating them as the final expression of the parties’ intentions. However, there are exceptions, such as clarifying ambiguities, addressing fraud, or showing post-contract modifications.

Question 2

Which of the following best describes an express warranty in a contract?

A) It only applies if it is made orally and not in writing

B) It must be implied from industry standards or trade usage

C) It is a specific promise made by one party about the quality or performance of a product or service

D) It cannot be enforced unless a condition precedent is satisfied

Answer: C) It is a specific promise made by one party about the quality or performance of a product or service

Explanation: An express warranty is a clear, specific promise about the quality, condition, or performance of a product or service, made by one party, typically in the contract or during negotiations. This warranty gives the other party a basis for recourse if the promised standards are not met. Unlike implied warranties, which are not explicitly stated, express warranties are directly communicated to the other party.

Question 3

When resolving ambiguities in a contract, which principle would a court most likely apply?

A) Automatically voiding the contract

B) Preferring handwritten terms over preprinted terms

C) Relying solely on oral agreements made prior to the contract

D) Enforcing the terms strictly according to industry usage without considering other factors

Answer: B) Preferring handwritten terms over preprinted terms

Explanation: Courts often give precedence to handwritten or typed terms over preprinted ones because handwritten or typed additions are viewed as more recent and specific representations of the parties’ intentions. This principle helps resolve ambiguities by focusing on terms that are more tailored to the unique circumstances of the agreement rather than standardized language.