Negligence is a foundational concept in tort law, focusing on the duty of care individuals owe to each other and the consequences of breaching that duty. This topic examines the essential elements of negligence, including duty, breach, causation, and damages, and how these elements interact in various factual scenarios. It emphasizes the standards used to assess reasonable care, foreseeability, and proximate cause, as well as defenses such as contributory and comparative negligence. Mastery of these principles is vital for analyzing liability and understanding the responsibilities imposed by law to prevent harm to others.

Learning Objectives

In studying “Negligence” for the MBE, you should learn to understand the elements required to establish a negligence claim: duty, breach, causation, and damages. Analyze how duty of care is determined based on the relationship between parties and the foreseeability of harm. Study the concept of breach of duty and how it is evaluated against the standard of a reasonable person in similar circumstances. Understand both actual and proximate causation, focusing on how each element contributes to liability. Evaluate defenses to negligence, including contributory negligence, comparative negligence, and assumption of risk. Additionally, apply these principles to hypothetical scenarios to identify potential negligence claims and defenses, ensuring thorough preparation for MBE-style questions.

Elements Required to Establish a Negligence Claim

To establish a negligence claim, a plaintiff must prove four essential elements: duty of care, breach of duty, causation, and damages. These elements create the foundation of negligence law, ensuring that a defendant can only be held liable if they owed a duty to the plaintiff, failed to meet that duty, and directly caused harm as a result. Here’s an in-depth look at each element required to establish a negligence claim:

1. Duty of Care

- Definition: Duty of care refers to the legal obligation one party owes to another to act reasonably and avoid causing harm. In negligence claims, the plaintiff must first establish that the defendant owed them a duty of care.

- Application: Courts determine whether a duty exists based on the relationship between the parties and the foreseeability of harm. Generally, a duty of care is owed to others when a reasonable person in the same situation would foresee that their actions might cause harm.

- Example: A driver has a duty of care to follow traffic laws and drive safely to protect other road users from foreseeable harm.

- Types of Duty:

- General Duty: In many situations, everyone owes a duty to avoid causing harm to others through reasonable actions (e.g., driving safely).

- Special Duty: Certain relationships, such as doctor-patient or employer-employee, impose specific duties of care due to the trust and reliance inherent in those relationships.

- Challenges: Establishing duty can be complex if the relationship between the parties is unclear or if the harm was not easily foreseeable.

2. Breach of Duty

- Definition: Breach of duty occurs when the defendant fails to meet the standard of care expected under the circumstances, effectively violating their duty of care. This failure to act as a reasonable person would in the same situation constitutes a breach.

- Standard of Care: The standard of care is typically based on what a “reasonable person” would do in similar circumstances. In specialized situations (e.g., medical or legal contexts), the standard of care may be based on what a competent professional in the same field would do.

- Example: A driver breaches their duty of care by running a red light, an action that falls below the standard of care expected of a reasonable driver.

- Challenges: Proving a breach of duty requires evidence that the defendant’s actions were unreasonable and failed to meet the required standard of care. Expert testimony may be needed in professional negligence cases to establish the appropriate standard and determine if it was breached.

3. Causation

- Definition: Causation requires a direct link between the defendant’s breach of duty and the plaintiff’s harm. The plaintiff must demonstrate that the defendant’s actions were the actual and proximate cause of their injury.

- Types of Causation:

- Actual Cause (Cause-in-Fact): The plaintiff must prove that the harm would not have occurred “but for” the defendant’s actions. This is a straightforward, factual connection between the defendant’s conduct and the injury.

- Proximate Cause (Legal Cause): The harm must also be closely related to the defendant’s actions in a way that is legally reasonable. Proximate cause limits liability to harms that were a foreseeable result of the defendant’s actions.

- Example: If a driver runs a red light and hits a pedestrian, causing an injury, the driver’s action is the actual cause of the injury. The harm (injury to the pedestrian) was also a foreseeable result of the action, satisfying proximate cause.

- Challenges: Causation can be difficult to prove when multiple factors contributed to the injury, especially if intervening events (known as superseding causes) break the causal chain.

4. Damages

- Definition: Damages refer to the actual harm, loss, or injury suffered by the plaintiff as a result of the defendant’s breach of duty. Without damages, there is no valid claim for negligence, as the law requires a tangible injury for compensation.

- Types of Damages:

- Compensatory Damages: Intended to make the plaintiff “whole” by covering medical expenses, lost wages, pain and suffering, and property damage directly resulting from the injury.

- Punitive Damages: Awarded in cases of gross negligence or malicious behavior, punitive damages are intended to punish the defendant and deter similar conduct. However, punitive damages are rare in negligence cases and are typically reserved for cases involving intentional misconduct.

- Example: In a slip-and-fall case, damages might include medical expenses for treating injuries, compensation for time off work, and payment for any ongoing physical therapy required.

- Challenges: Proving damages requires evidence of both the injury and its financial impact on the plaintiff. Calculating damages, particularly for non-economic losses like pain and suffering, can be complex and often requires supporting documentation or expert testimony.

Duty of Care: Determination Based on Relationship and Foreseeability

Duty of care is a foundational concept in negligence law, requiring individuals and entities to act reasonably to avoid causing harm to others. To establish a duty of care, courts typically consider two main factors: the relationship between the parties and the foreseeability of harm. These elements help determine whether a defendant owed a duty to the plaintiff, setting the standard for assessing liability in a negligence claim.

1. Relationship Between the Parties

- Definition: Duty of care is often determined by the relationship between the parties involved. When a relationship inherently requires one party to act responsibly toward another, a duty of care is more likely to be established.

- Types of Relationships That Impose Duty:

- Personal Relationships: Family members, guardians, and caregivers have an inherent duty to prevent foreseeable harm to those under their care, such as children or vulnerable adults.

- Professional Relationships: Certain professionals owe a heightened duty of care to their clients, patients, or customers due to the trust and reliance placed on them. Examples include doctors to patients, lawyers to clients, and accountants to clients.

- Landowner-Visitor Relationships: Property owners owe varying degrees of duty depending on the status of visitors (invitees, licensees, or trespassers). For example, property owners owe a duty to maintain safe conditions for invited guests.

- Special Circumstances or Voluntary Assumptions of Duty: In some cases, individuals voluntarily take on a duty of care. For instance, a bystander who starts helping an injured person may owe a duty to act reasonably in their assistance.

- Example: A doctor has a duty to provide competent medical care to a patient. This relationship creates a specific duty of care based on the doctor’s professional obligations and the patient’s reliance on their expertise.

- Challenges: Determining duty based on relationship can be complex if the relationship between the parties is informal, distant, or incidental. In such cases, courts may rely more on the foreseeability of harm to establish duty.

2. Foreseeability of Harm

- Definition: Foreseeability refers to whether a reasonable person in the defendant’s position could predict that their actions might cause harm to someone in the plaintiff’s position. Courts consider whether the risk of harm was apparent or should have been apparent to a reasonable person.

- Application of Foreseeability:

- Objective Standard: Foreseeability is assessed objectively, meaning the court considers what a reasonable person would have anticipated in similar circumstances, rather than the defendant’s subjective perspective.

- Scope of Potential Harm: Courts examine the scope of potential harm, including the likelihood and severity of harm, to determine whether it was reasonable to expect harm could occur. This helps establish if the duty was to prevent harm to the specific plaintiff or to the general public.

- Example: A store owner who mops the floor without putting up a warning sign could foresee that a customer might slip and get injured. This foreseeability creates a duty to take precautions, such as posting a “wet floor” sign.

- Challenges: Foreseeability can be difficult to establish when harm occurs due to an unusual or unexpected chain of events. Courts may limit duty if the harm was too remote or unpredictable, applying the concept of “proximate cause” to prevent unlimited liability.

Breach of Duty and the Reasonable Person Standard

Breach of duty is a key element in a negligence claim, requiring proof that the defendant failed to meet the standard of care expected under the circumstances. The reasonable person standard is used to determine whether the defendant acted as a reasonably careful person would have in a similar situation. This standard helps establish whether the defendant’s conduct was negligent, making it a foundational concept in determining liability in negligence cases.

1. Breach of Duty

- Definition: Breach of duty occurs when a person or entity fails to act with the level of care that a reasonable person would exercise in the same circumstances. If the defendant’s actions fall below the standard expected, they are considered to have breached their duty.

- Establishing a Breach:

- Evidence of Unsafe Conduct: The plaintiff must show that the defendant’s actions were unreasonably unsafe or failed to meet the expected standard of care.

- Deviation from Expected Behavior: Courts assess whether the defendant’s conduct deviated from what would be expected of a reasonable person, professional, or entity in similar circumstances.

- Example: If a driver exceeds the speed limit and causes an accident, this act may constitute a breach of duty because a reasonable driver would follow traffic laws to prevent harm.

2. The Reasonable Person Standard

- Definition: The reasonable person standard is an objective test used to evaluate how a hypothetical “reasonable person” would act under similar circumstances. This standard is used to measure the defendant’s conduct against societal expectations of caution and care.

- Characteristics of the Reasonable Person:

- The reasonable person is assumed to be cautious, responsible, and attentive to avoid causing harm to others.

- This standard is objective, meaning it does not consider the defendant’s personal characteristics, such as specific skills, knowledge, or inexperience.

- Application: Courts apply the reasonable person standard to determine if the defendant’s actions were reasonable or fell short of what society would expect. For example, a reasonable person would understand that speeding increases the risk of accidents, and therefore, not speeding is considered the standard.

- Example: In a case where a pedestrian is struck while crossing the street at a crosswalk, the court would evaluate whether the driver exercised the caution that a reasonable person would have in that situation, such as yielding to the pedestrian.

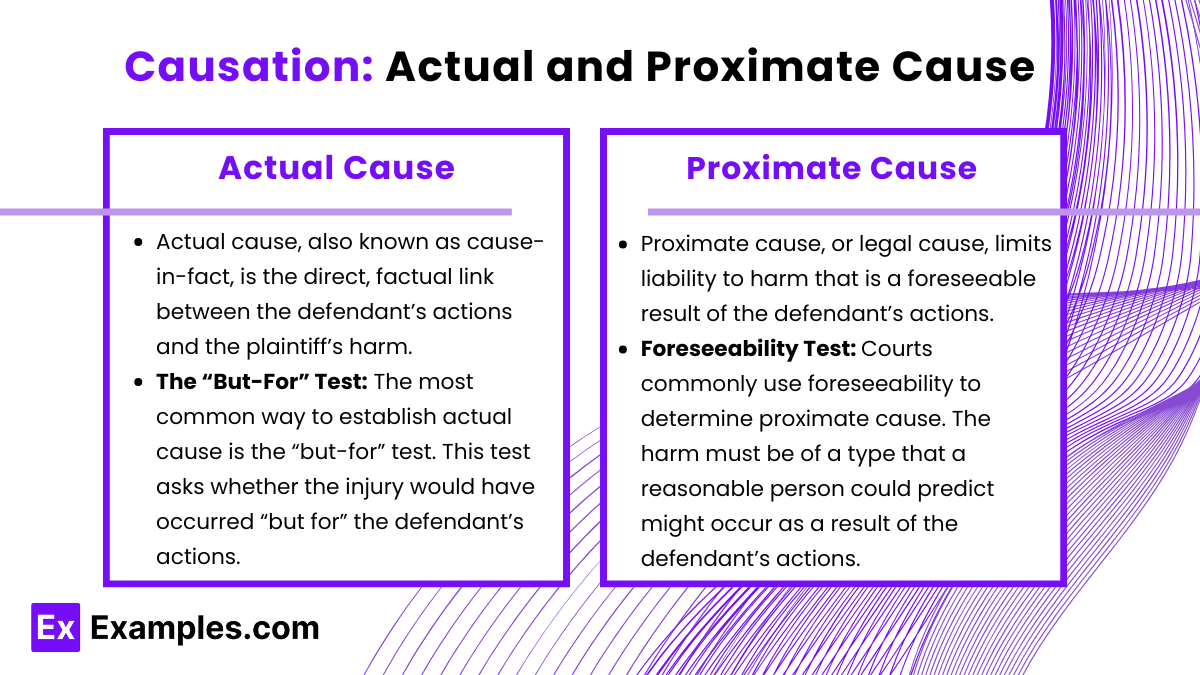

Causation: Actual and Proximate Cause

Causation is a critical element in a negligence claim, requiring the plaintiff to prove that the defendant’s actions caused their harm. Causation has two components: actual cause and proximate cause. These components work together to establish a clear and legally sufficient connection between the defendant’s conduct and the plaintiff’s injury.

1. Actual Cause

- Definition: Actual cause, also known as cause-in-fact, is the direct, factual link between the defendant’s actions and the plaintiff’s harm. It answers the question, “Did the defendant’s actions actually cause the injury?”

- The “But-For” Test: The most common way to establish actual cause is the “but-for” test. This test asks whether the injury would have occurred “but for” the defendant’s actions. If the harm would not have happened without the defendant’s conduct, then actual cause is established.

- Example: If a driver runs a red light and hits a pedestrian, causing injury, the actual cause is clear. But for the driver running the red light, the pedestrian would not have been injured.

- Alternative Tests:

- Substantial Factor Test: In cases where multiple factors contributed to the harm, courts may apply the substantial factor test. This test examines whether the defendant’s actions were a substantial factor in causing the injury, even if other factors also played a role.

- Concurrent Causation: When two or more defendants independently cause harm, and each action alone would have caused the injury, both defendants can be held liable. This is often used in environmental and toxic tort cases.

2. Proximate Cause

- Definition: Proximate cause, or legal cause, limits liability to harm that is a foreseeable result of the defendant’s actions. It addresses the question, “Was the injury a foreseeable consequence of the defendant’s conduct?”

- Purpose: Proximate cause helps ensure that liability is fair by preventing defendants from being held responsible for highly unexpected or remote consequences of their actions. It imposes a “legal cut-off” to limit liability to injuries that have a reasonably close connection to the defendant’s conduct.

- Foreseeability Test: Courts commonly use foreseeability to determine proximate cause. The harm must be of a type that a reasonable person could predict might occur as a result of the defendant’s actions.

- Example: A restaurant negligently leaves broken glass on the floor, and a customer cuts their foot. This injury is a foreseeable result of the restaurant’s negligence, establishing proximate cause. However, if the customer had a unique medical condition that caused an unusual complication, the restaurant might not be liable for the remote, unforeseeable consequence.

- Intervening and Superseding Causes:

- Intervening Cause: An event that occurs after the defendant’s action and contributes to the harm. If the intervening cause was foreseeable, it does not break the chain of causation.

- Superseding Cause: A type of intervening cause that is so unexpected or unforeseeable that it breaks the chain of causation, absolving the defendant of liability for subsequent harm.

Examples

Example 1: Medical Malpractice

A doctor failing to diagnose a condition that is easily detectable, such as missing signs of a heart attack, constitutes negligence. If the doctor overlooks symptoms or provides incorrect treatment due to carelessness, this can result in harm to the patient. In such cases, the doctor’s failure to meet the standard of care is considered negligent.

Example 2: Car Accident Due to Distracted Driving

A driver texting while driving and failing to notice a red light, causing an accident, is an example of negligence. The driver’s inattention to the road and failure to obey traffic laws leads to harm, demonstrating that negligence occurs when an individual does not take reasonable care to avoid causing damage to others.

Example 3: Slip and Fall in a Store

A shopper slips on a wet floor in a supermarket because the store did not put up a “Wet Floor” sign or fail to clean the spill in a timely manner. This is an example of negligence by the store owner, who has a duty to maintain a safe environment for customers, and their failure to do so led to injury.

Example 4: Failure to Maintain Property

A landlord who neglects to repair a broken staircase, despite being informed, and a tenant falls and injures themselves as a result is an example of negligence. The landlord has a responsibility to maintain the property and ensure it is safe for tenants, and failure to do so can result in legal consequences.

Example 5: Product Defects

A manufacturer who produces a faulty electrical appliance without testing it properly, leading to fires or injuries when consumers use it, is an example of negligence. The manufacturer has a duty to ensure that their products are safe for use and do not present a foreseeable risk of harm to the consumer. Negligence occurs when this duty is ignored.

Practice Questions

Question 1

Which of the following is an example of negligence?

A) A person driving within the speed limit and causing an accident due to weather conditions.

B) A person failing to fix a broken sidewalk despite being aware of it and someone tripping on it.

C) A person legally walking on a crosswalk without causing any harm.

D) A person getting injured while participating in a risky sport with proper equipment.

Correct Answer: B) A person failing to fix a broken sidewalk despite being aware of it and someone tripping on it.

Explanation: Negligence occurs when a person fails to take reasonable care to avoid causing harm to others. In this case, the person was aware of the broken sidewalk but did not take action to fix it, which led to someone else getting hurt. This failure to maintain the property creates a foreseeable risk of harm, making it an example of negligence.

Question 2

In a negligence case, what must the plaintiff prove?

A) That the defendant intended to cause harm.

B) That the defendant had a duty of care, breached that duty, and caused harm.

C) That the plaintiff contributed to the harm.

D) That the defendant was not insured.

Correct Answer: B) That the defendant had a duty of care, breached that duty, and caused harm.

Explanation: To prove negligence, the plaintiff must demonstrate that the defendant had a duty to act in a reasonable manner (duty of care), failed to do so (breach of duty), and that this failure directly caused harm to the plaintiff. The intent to cause harm is not required in negligence cases, as it focuses on the failure to act responsibly.

Question 3

Which of the following is not an element of negligence?

A) Breach of duty

B) Causation

C) Intention to cause harm

D) Damages

Correct Answer: C) Intention to cause harm.

Explanation: Negligence is based on a failure to exercise reasonable care, not on the intent to cause harm. The four elements of negligence are: duty of care, breach of duty, causation (showing the breach led to harm), and damages (showing that harm occurred). Intent to cause harm is not required for a negligence claim, unlike in intentional torts.