Preparing for the MBE Exam requires a thorough grasp of "Performance, Breach, and Discharge," a critical area of contract law. Mastery of the rules governing contract fulfillment, remedies for breach, and conditions for discharge is essential. This knowledge aids in resolving disputes, enforcing rights, and navigating contract terminations effectively for exam success.

Learning Objective

In studying "Performance, Breach, and Discharge" for the MBE Exam, you should understand the rules governing contract performance, including the duties of parties, substantial performance, and the role of conditions. Analyze different types of breaches (material vs. minor), anticipatory repudiation, and their legal consequences. Evaluate available remedies for breach, such as damages and specific performance. Additionally, explore how contracts may be discharged by agreement, impossibility, frustration of purpose, or other doctrines. Apply this knowledge to practical scenarios and legal disputes to enhance your ability to interpret and resolve contract-related issues in MBE questions.

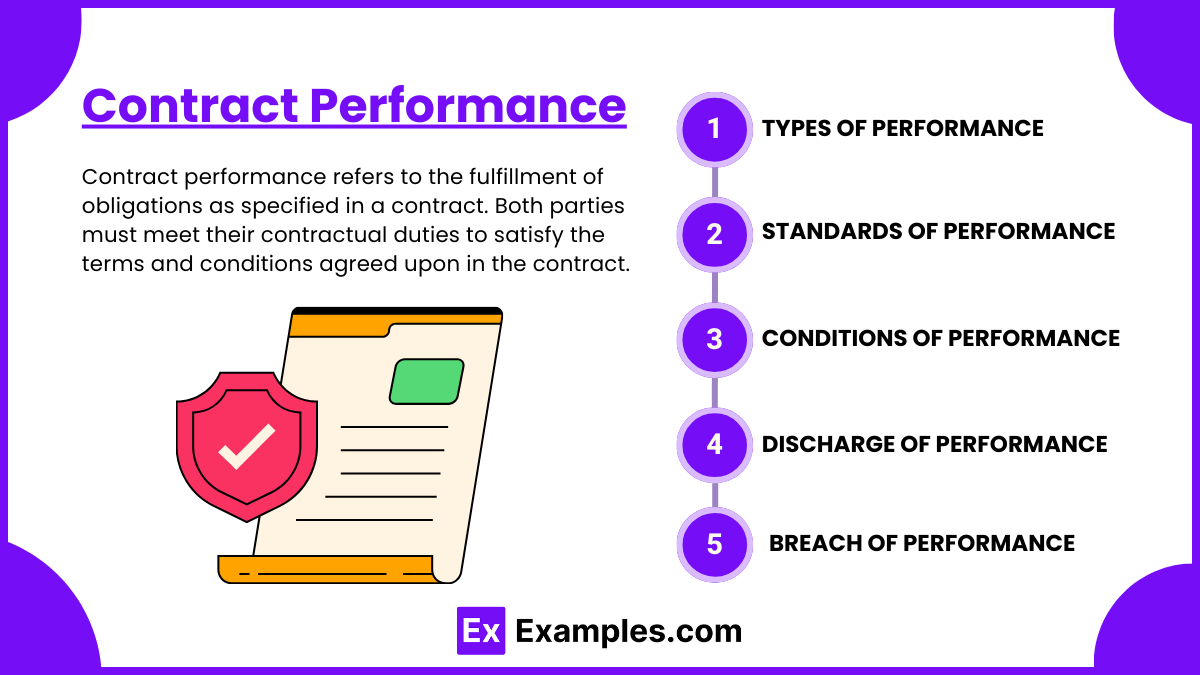

Contract Performance

Contract performance refers to the fulfillment of obligations as specified in a contract. Both parties must meet their contractual duties to satisfy the terms and conditions agreed upon in the contract. Understanding the principles of performance is crucial for determining whether each party has met its obligations, whether there has been a breach, and what remedies may be available. Here is a detailed exploration of key aspects of contract performance.

1. Types of Performance

Complete (or Full) Performance: When a party fulfills all of the contract's terms and conditions exactly as agreed, it is considered complete performance. This type of performance fully discharges the party's contractual duties and entitles them to enforce the other party’s obligations.

Example: A contractor completes a building project according to the specifications and timelines stated in the contract.

Substantial Performance: Occurs when a party completes the major requirements of the contract, leaving only minor deviations or defects. In this case, the performing party may still be entitled to payment, but the other party may seek compensation for any deficiencies.

Example: A painter finishes 98% of a painting job but misses a small section. The client is obligated to pay, minus the value of the incomplete work.

Partial Performance: This occurs when only a portion of the agreed obligations is completed, and it often constitutes a breach of contract unless excused or accepted by the other party.

2. Standards of Performance

Objective Standard: Performance is judged by whether a reasonable person would consider the obligations to have been met. Most contracts apply this standard to evaluate whether the terms have been properly fulfilled.

Subjective Standard: In some cases, performance may be evaluated based on one party's personal satisfaction (e.g., an art commission). This standard is often used in contracts where personal taste, opinion, or discretion is involved.

Time for Performance: If a contract specifies a deadline for performance, failure to meet this timeline can constitute a breach, unless excused or waived by the other party. If no time is specified, a "reasonable time" is implied.

3. Conditions of Performance

Conditions Precedent: An event that must occur before a party is obligated to perform their contractual duties.

Example: A buyer's obligation to purchase a house may be contingent on securing mortgage approval.

Conditions Subsequent: An event that, if it occurs, releases a party from an existing obligation.

Example: A lease may terminate if the tenant fails to maintain insurance coverage.

Concurrent Conditions: These occur when the parties' duties must be performed simultaneously.

Example: In a sales contract, the buyer’s obligation to pay and the seller’s obligation to deliver goods occur concurrently.

4. Discharge of Performance

Discharge by Agreement: Parties can mutually agree to discharge their contractual obligations. This can include rescission (mutual cancellation), modification, or novation (substitution of a new contract).

Discharge by Performance: Once both parties have fully performed their duties, the contract is considered discharged.

Discharge by Impossibility or Frustration of Purpose: If unforeseen circumstances make performance impossible (e.g., death of a key performer in a personal services contract) or frustrate the contract’s purpose, performance may be excused.

Discharge by Operation of Law: Certain events, such as bankruptcy or the expiration of the statute of limitations, can discharge obligations by operation of law.

5. Breach of Performance

Material Breach: A significant failure to perform that permits the other party to terminate the contract and sue for damages.

Minor (or Partial) Breach: A breach that does not substantially affect the value of the contract; the non-breaching party must still perform but may sue for damages.

Anticipatory Repudiation: When one party clearly communicates their intention not to perform their obligations before performance is due. This allows the non-breaching party to treat the contract as breached immediately and seek remedies.

Understanding contract performance is crucial for determining whether obligations have been fulfilled and what legal consequences follow if they are not. It forms the basis for resolving disputes over contract fulfillment and identifying available remedies for breaches.

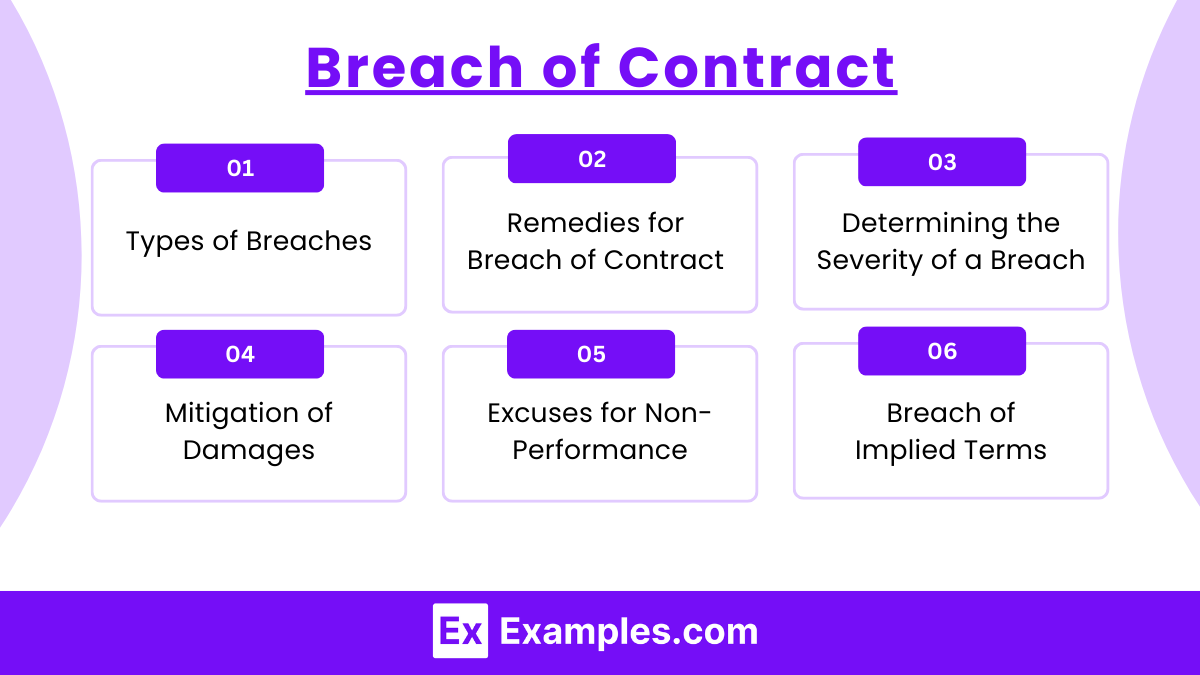

Breach of Contract

A breach of contract occurs when one party fails to fulfill their obligations under a legally binding agreement without a valid legal excuse. Breaches can take many forms, ranging from a complete failure to perform to only partial compliance with contract terms. When a breach occurs, it impacts the rights and duties of both parties and gives rise to remedies that may be sought by the non-breaching party. Understanding different types of breaches and their consequences is critical for contract enforcement and dispute resolution.

1. Types of Breaches

Material Breach: A material breach is a serious violation of the contract that significantly affects the rights of the non-breaching party. This type of breach goes to the essence of the contract and defeats the purpose of the agreement, allowing the non-breaching party to:

Terminate the contract.

Refuse to perform any further obligations.

Seek damages for losses incurred.

Example: A contractor hired to build a house fails to complete major portions of the work, rendering the house uninhabitable.

Minor (or Partial) Breach: A minor breach occurs when a party fails to fulfill some part of their contractual obligations but does not destroy the overall purpose of the contract. The non-breaching party is generally not excused from performance but may seek compensation for any damages caused by the breach.

Example: A landscaper completes most of the agreed-upon work but omits one section. The client must still pay for the work completed but can seek damages for the uncompleted portion.

Anticipatory Breach (or Anticipatory Repudiation): This occurs when one party clearly indicates, before their performance is due, that they will not or cannot fulfill their contractual obligations. The non-breaching party can treat this as a breach and seek remedies immediately without waiting for the scheduled performance.

Example: A supplier informs a retailer that they will not be able to deliver the goods on the agreed date, months in advance of the deadline.

2. Remedies for Breach of Contract

When a breach occurs, the non-breaching party may seek various remedies, depending on the nature of the breach and the contract terms.

Monetary Damages: The most common remedy for breach, monetary damages compensate the non-breaching party for losses incurred due to the breach.

Compensatory Damages: Intended to make the injured party whole by covering direct losses and costs incurred due to the breach.

Consequential Damages: Indirect damages that result from the breach, provided they were foreseeable at the time of contract formation.

Liquidated Damages: Pre-agreed amounts specified in the contract that the breaching party must pay if they breach certain terms. Enforceable only if the amount is a reasonable estimate of potential damages.

Punitive Damages: Rare in contract law; typically awarded only if the breach involves fraud, malice, or other wrongful conduct.

Specific Performance: This equitable remedy requires the breaching party to perform their obligations as specified in the contract. It is typically used when monetary damages are inadequate, such as in contracts involving unique goods or real estate.

Example: A buyer may seek specific performance to force the seller to convey a specific piece of property if the seller breaches the contract.

Rescission: The contract is terminated, and both parties are released from their obligations. This remedy may be sought if a breach is material or if there was fraud, mistake, or misrepresentation involved in contract formation.

Example: A party who entered a contract based on false representations may rescind the agreement.

Reformation: This remedy allows the court to modify or rewrite a contract to reflect the true intentions of the parties, often used when there is a mutual mistake in the contract’s terms.

3. Determining the Severity of a Breach

Courts consider several factors when determining whether a breach is material or minor:

Extent of Performance: The extent to which the breaching party performed their contractual duties.

Impact on the Non-Breaching Party: Whether the breach deprives the non-breaching party of a significant benefit or defeats the purpose of the contract.

Possibility of Cure: Whether the breaching party can remedy the breach within a reasonable timeframe.

Intent of the Parties: Evidence of the parties' intent regarding the importance of the breached term.

4. Mitigation of Damages

The non-breaching party has a duty to mitigate their damages by taking reasonable steps to minimize the impact of the breach. If they fail to do so, the amount of damages they can recover may be reduced.

Example: If a landlord breaches a lease agreement, the tenant must make reasonable efforts to find alternative housing rather than incurring unnecessary losses.

5. Excuses for Non-Performance

Certain situations may excuse a party's performance under a contract:

Impossibility: If performance becomes impossible due to unforeseen events (e.g., destruction of subject matter), the duty to perform may be discharged.

Frustration of Purpose: If the purpose of the contract is destroyed by an unexpected event, performance may be excused.

Waiver: A party may voluntarily relinquish their right to enforce a provision of the contract.

6. Breach of Implied Terms

Contracts often contain implied terms, such as the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing. Breach of these terms can result in legal consequences, just as breaches of express terms can.

Understanding the various forms of breaches, available remedies, and related legal concepts enables parties to navigate contract disputes, enforce their rights, and seek appropriate resolutions when obligations are not met.

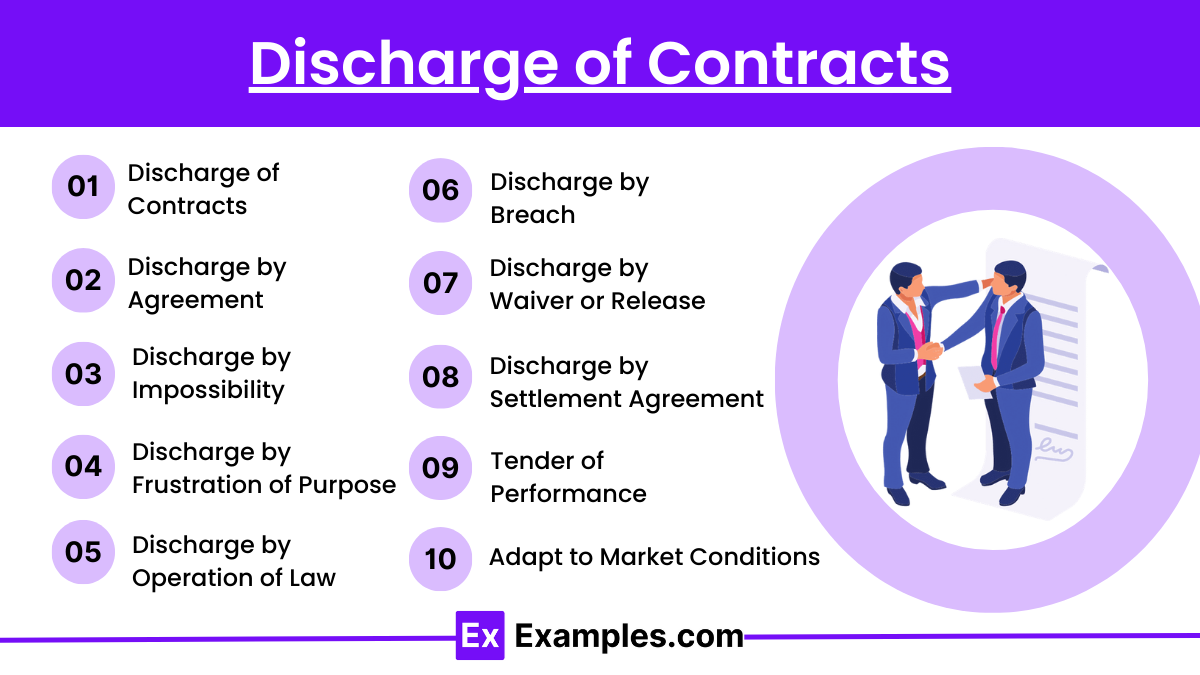

Discharge of Contracts

The discharge of a contract refers to the termination of contractual obligations, meaning the parties are released from further responsibilities under the agreement. A contract may be discharged through various methods, each of which determines how and when obligations end. Understanding these methods is essential for determining when a contract ceases to be legally binding and what rights and duties may remain.

1. Discharge by Performance

This is the most common method of discharging a contract. When all parties fulfill their contractual obligations as agreed, the contract is discharged.

Complete Performance: All terms and conditions of the contract are fully and exactly met by the parties.

Example: A contractor completes a building project according to the specifications in the contract, and the property owner makes the agreed-upon payment.

Substantial Performance: This occurs when a party fulfills the major terms of the contract but may have minor deviations or defects. In such cases, the performing party is entitled to payment minus the cost of remedying any defects.

Example: A contractor completes a building project but fails to paint one small section. The client must pay for the work completed, less the cost to paint the section.

2. Discharge by Agreement

Contracts may be discharged by the mutual agreement of the parties through various means:

Mutual Rescission: Both parties agree to cancel the contract, releasing each other from their obligations. This is only possible if neither party has fully performed.

Example: Two parties agree to terminate a lease agreement before the lease term expires.

Novation: The original contract is discharged by replacing one or more of the original parties or substituting a new contract in place of the original one, with the agreement of all involved parties.

Example: A tenant transfers their lease obligations to another person, with the landlord's approval, creating a new contract between the landlord and the new tenant.

Accord and Satisfaction: The parties agree to accept different performance than originally agreed upon. Accord is the agreement to change the obligation, and satisfaction is the fulfillment of the new obligation.

Example: A debtor offers to pay less than the full amount owed, and the creditor accepts this partial payment as full settlement.

Modification: The original contract terms are modified by mutual agreement, resulting in a new set of terms that discharge the original obligations.

3. Discharge by Impossibility or Impracticability

A contract may be discharged if an unforeseen event makes performance objectively impossible or extremely impracticable.

Impossibility: Performance is impossible if it cannot be carried out due to events such as the destruction of the subject matter, death or incapacity of a party in a personal services contract, or a change in law that makes the performance illegal.

Example: A musician contracted to perform at a concert dies before the performance date, discharging the contract due to impossibility.

Commercial Impracticability: Performance may be excused if it becomes extremely difficult or costly due to unforeseen circumstances, provided the event was not contemplated by the parties at the time of contract formation.

Example: A supplier’s ability to deliver goods is severely impacted by an unexpected trade embargo, making performance impracticable.

4. Discharge by Frustration of Purpose

This occurs when an unforeseen event substantially frustrates the primary purpose of the contract, and both parties were aware of this purpose at the time of formation. The contract is discharged if the event fundamentally changes the contract's expected value or purpose.

Example: A person rents a venue for a parade viewing, but the parade is unexpectedly canceled. The contract may be discharged because the primary purpose is frustrated.

5. Discharge by Operation of Law

Contracts may be discharged through legal mechanisms or events, including:

Bankruptcy: A debtor’s contractual obligations may be discharged under bankruptcy law, releasing them from further performance of debt obligations.

Statute of Limitations: If the statute of limitations for enforcing a contract has expired, the contract is discharged, meaning no legal action can be taken to enforce it.

Alteration of Contract: If one party intentionally alters a written contract without the other party's consent, the contract may be discharged.

6. Discharge by Breach

A breach of contract can lead to its discharge if the breach is material or significant enough to defeat the purpose of the agreement.

Material Breach: The non-breaching party may treat the contract as terminated and sue for damages if the breach goes to the essence of the agreement.

Anticipatory Repudiation: If one party clearly indicates that they will not perform their contractual duties, the non-breaching party can treat the contract as discharged and seek remedies.

7. Discharge by Waiver or Release

A party may unilaterally waive their right to enforce a particular term or condition of the contract, resulting in a discharge of that specific obligation. Similarly, a release agreement may discharge one or both parties from further obligations under the contract.

8. Discharge by Settlement Agreement

The parties may agree to resolve a contract dispute through a settlement, which discharges the original contractual obligations and creates new ones.

9. Tender of Performance

If a party offers to perform their contractual duties but the other party refuses to accept the performance, the offering party is discharged from their obligations. This applies when the offer to perform is in accordance with the terms of the contract.

Examples

Example 1: Complete Performance

Scenario: A contractor agrees to build a house according to specific blueprints and finishes the construction exactly as agreed upon. The homeowner pays the full contract price.

Legal Point: This is an example of complete performance. The contractor fulfilled all contractual obligations as specified, discharging their duty, and the homeowner is obligated to pay.

Example 2: Substantial Performance and Minor Breach

Scenario: A painter completes 95% of the work on a building, leaving a small portion unfinished. The building owner deducts the cost of completing the work from the final payment.

Legal Point: This illustrates substantial performance. The painter is entitled to payment for the completed work, but the building owner may seek a deduction for the unfinished portion, reflecting a minor breach.

Example 3: Material Breach

Scenario: A supplier fails to deliver essential goods required by a retailer for a major event. The retailer suffers significant losses as a result.

Legal Point: This is a material breach, as the supplier’s failure to perform undermines the contract’s purpose. The retailer may terminate the contract and sue for damages caused by the breach.

Example 4: Anticipatory Breach

Scenario: A contractor informs a client two months before a project deadline that they will not be able to complete the work. The client immediately seeks a new contractor and sues for damages.

Legal Point: The contractor’s statement constitutes anticipatory breach, allowing the client to treat the contract as breached and seek remedies before the original performance date.

Example 5: Discharge by Impossibility

Scenario: A musician is contracted to perform at a concert but unexpectedly dies before the event. The contract with the event organizer is discharged.

Legal Point: This demonstrates discharge by impossibility. The musician’s death makes it objectively impossible to fulfill the contract, releasing both parties from their obligations.

Practice Questions

Question 1

What is the effect of a party substantially performing their obligations under a contract?

A) The party is treated as having fully performed and owes no compensation to the other party.

B) The party is entitled to payment minus any damages for the minor breach.

C) The contract is automatically terminated.

D) The non-breaching party can refuse any payment.

Answer: B) The party is entitled to payment minus any damages for the minor breach.

Explanation: Substantial performance occurs when a party completes the major aspects of their contractual obligations, leaving minor deviations or defects. In such cases, the performing party is entitled to payment, although the non-breaching party may seek compensation for the cost of remedying any minor deficiencies.

Question 2

Which of the following best describes an anticipatory breach?

A) Failure to perform contractual duties on the specified date.

B) A party indicating, before the due date, that they will not perform.

C) Performance completed but not accepted by the other party.

D) A minor deviation from contract terms without notice.

Answer: B) A party indicating, before the due date, that they will not perform.

Explanation: An anticipatory breach occurs when one party clearly communicates their intention not to fulfill their contractual obligations before the performance is due. This allows the non-breaching party to treat the contract as breached immediately and seek remedies, such as damages or alternative arrangements.

Question 3

Under what circumstances is a contract discharged by impossibility?

A) When both parties agree to cancel the contract.

B) When a party fails to meet a non-essential term of the agreement.

C) When an unforeseen event makes performance objectively impossible.

D) When there is a change in the economic conditions affecting profitability.

Answer: C) When an unforeseen event makes performance objectively impossible.

Explanation: Discharge by impossibility occurs when a party cannot fulfill their contractual duties due to an unforeseen event beyond their control, such as death, destruction of the subject matter, or a change in law. This releases both parties from further obligations, provided the event was not foreseeable and prevents performance altogether.