In the study of AP English Language and Composition, understanding and interpreting the meaning in poetic structure is a vital skill. This involves analyzing how elements like form, meter, and rhyme scheme contribute to a poem’s overall effect. Mastering this skill not only aids in academic essay writing but also enhances the ability to craft compelling argumentative speeches. By examining rhetorical sentences and other structural components, students can uncover deeper meanings and themes within poems. This guide aims to provide the tools necessary to excel in the analysis of poetic structure, a key aspect of AP English Language and Literature.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this lesson on understanding and interpreting meaning in poetic structure, students will be able to develop a final thesis statement that clearly articulates their interpretation of a poem. They will enhance their critical thinking skills by analyzing how rhetorical sentences and structural elements contribute to the poem’s meaning. Students will practice writing rhetorical essays, persuasive essays, expository essays, and explanatory essays, using cumulative sentences to build and support their arguments effectively.

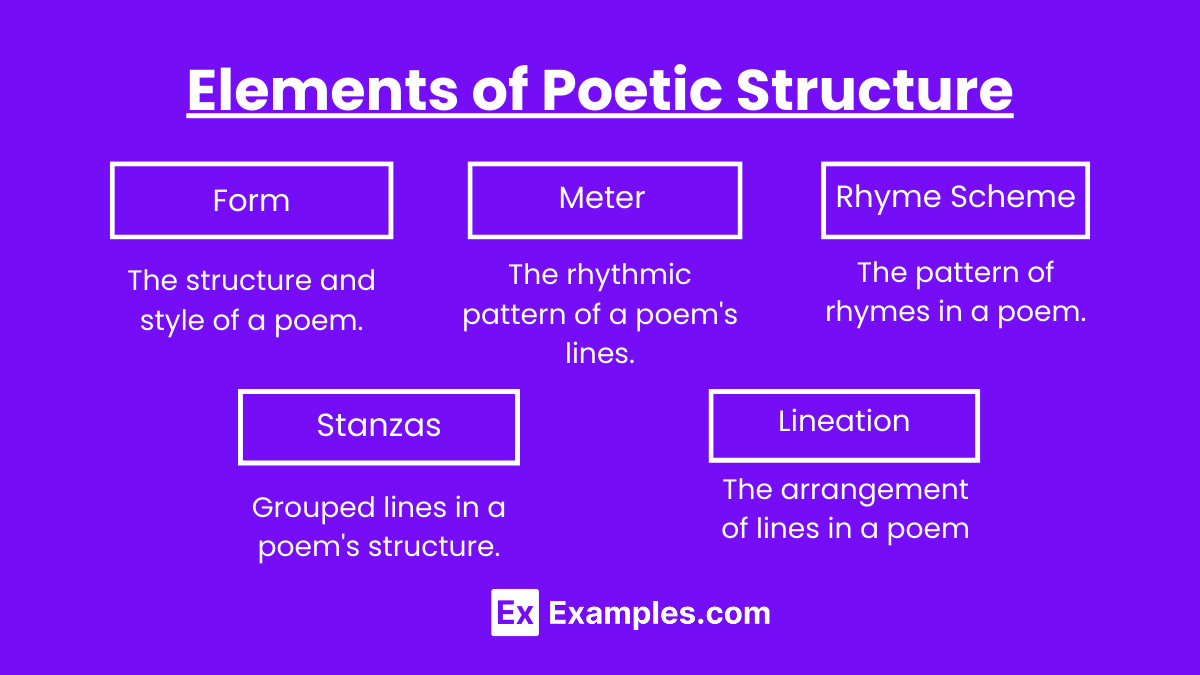

Elements of Poetic Structure

Form:

- Types of Poetic Forms: Sonnet, villanelle, haiku, free verse, etc.

- Impact on Meaning: The choice of form can influence the poem’s rhythm, pacing, and how the reader perceives its themes.

- Example: A Shakespearean sonnet’s strict structure contrasts with the freedom of free verse, each serving different expressive purposes.

Meter:

- Definition: The pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables in a line of poetry.

- Common Meters: Iambic pentameter, trochaic tetrameter, anapestic trimeter, etc.

- Effect on Meaning: Meter can enhance the musical quality of a poem and emphasize particular words or ideas.

- Example: Iambic pentameter often gives a poem a formal, elevated tone, suitable for grand themes.

Rhyme Scheme:

- Definition: The pattern of rhymes at the end of each line of a poem.

- Types: Couplet (AA), alternate rhyme (ABAB), enclosed rhyme (ABBA), etc.

- Contributions to Meaning: Rhyme schemes can create a sense of unity, emphasize connections between ideas, or contribute to the overall mood.

- Example: The ABAB rhyme scheme in Robert Frost’s “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” creates a gentle, flowing rhythm that reflects the poem’s contemplative mood.

Stanzas:

- Definition: Groups of lines separated by spaces in a poem.

- Types: Quatrain, tercet, couplet, sestet, etc.

- Role in Meaning: Stanza breaks can indicate shifts in tone, subject, or perspective.

- Example: In W.B. Yeats’s “The Second Coming,” the transition between stanzas marks a shift from describing chaos to foretelling the arrival of a new age.

Lineation:

- Enjambment: The continuation of a sentence without a pause beyond the end of a line.

- Effect: Creates a sense of movement and urgency.

- End-stopping: When a line of poetry ends with a period or definite punctuation mark.

- Effect: Provides a sense of closure or finality.

Analyzing Poetic Structure

Case Study: “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night” by Dylan Thomas

- Form: Villanelle

- Meter: Iambic pentameter

- Rhyme Scheme: ABA ABA ABA ABA ABA ABAA

- Analysis: The repetitive structure and strict form of the villanelle mirror the poem’s urgent plea against death. The alternating rhyme scheme emphasizes the struggle between resignation and defiance.

Case Study: “The Waste Land” by T.S. Eliot

- Form: Free verse with varied structure

- Meter: Varied

- Rhyme Scheme: Irregular

- Analysis: The fragmented structure and shifting meters reflect the chaos and disillusionment of the modern world. The irregular rhyme scheme and diverse voices within the poem enhance its themes of fragmentation and despair.

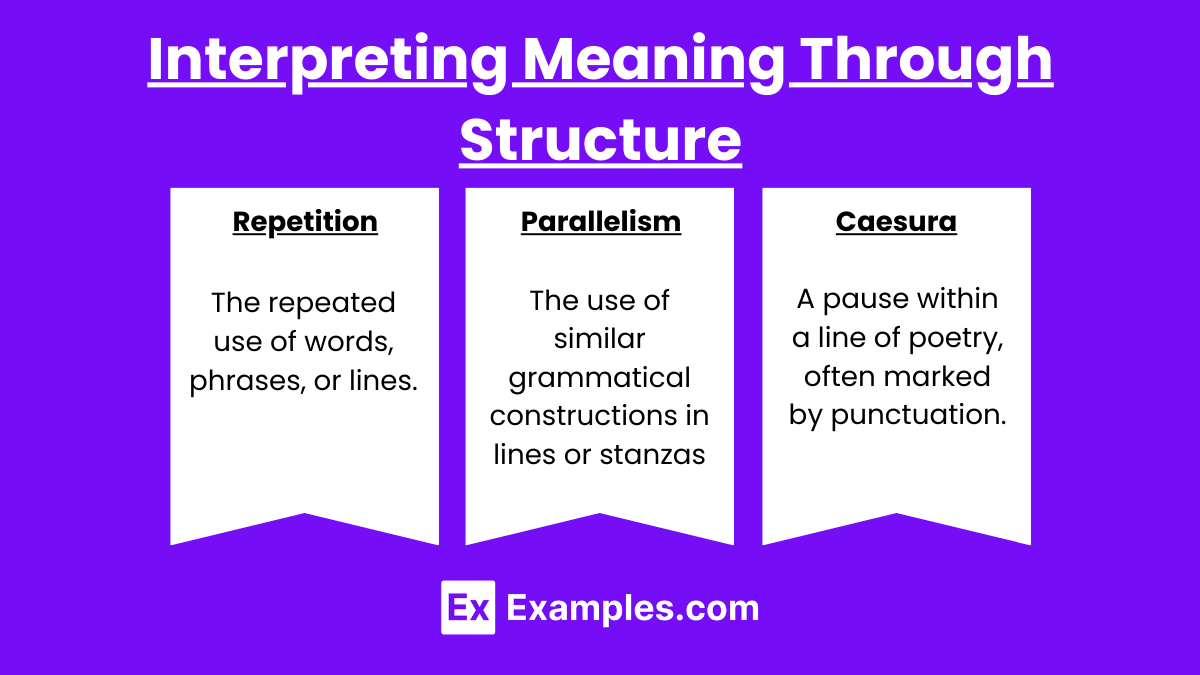

Interpreting Meaning Through Structure

Repetition:

- Definition: The repeated use of words, phrases, or lines.

- Function: Reinforces key themes and creates rhythm.

- Example: In Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven,” the repeated refrain “Nevermore” builds a sense of inevitability and despair.

Parallelism:

- Definition: The use of similar grammatical constructions in lines or stanzas.

- Function: Enhances the coherence and flow of the poem, emphasizing connections between ideas.

- Example: The parallel structure in Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself” emphasizes the poet’s connection with the broader human experience.

Caesura:

- Definition: A pause within a line of poetry, often marked by punctuation.

- Function: Creates a break in the rhythm, drawing attention to a particular word or phrase.

- Example: In Emily Dickinson’s “Because I could not stop for Death,” the caesura in the line “We paused before a House that seemed / A Swelling of the Ground” highlights the transition from life to death.