Elasticity is a crucial concept in AP Microeconomics that measures the responsiveness of quantity demanded or supplied to changes in various economic factors, such as price, income, or the prices of related goods. By analyzing elasticity, students can understand how consumers and producers react to market fluctuations, aiding in the prediction of behavior and the formulation of effective business and policy strategies. Mastery of elasticity concepts enables a deeper comprehension of market dynamics and enhances the ability to tackle complex economic problems on the exam.

Free AP Microeconomics Practice Test

Learning Objectives

When studying elasticity for AP Microeconomics, you should focus on understanding how price elasticity of demand and supply measure the responsiveness of quantity demanded or supplied to price changes. Learn to calculate and interpret income elasticity of demand and cross-price elasticity to distinguish between normal, inferior, substitute, and complementary goods. Explore the factors that influence elasticity, such as time horizon and availability of substitutes, and how elasticity affects consumer behavior, business pricing strategies, and tax incidence on markets.

What is Elasticity ?

Elasticity is a measure of how responsive quantity demanded or supplied is to changes in other economic variables, such as price, income, or the price of related goods. It is essential in both microeconomics and macroeconomics, as it helps analyze the efficiency of markets and predict the effects of economic policies and shocks.

1. Price Elasticity of Demand (PED)

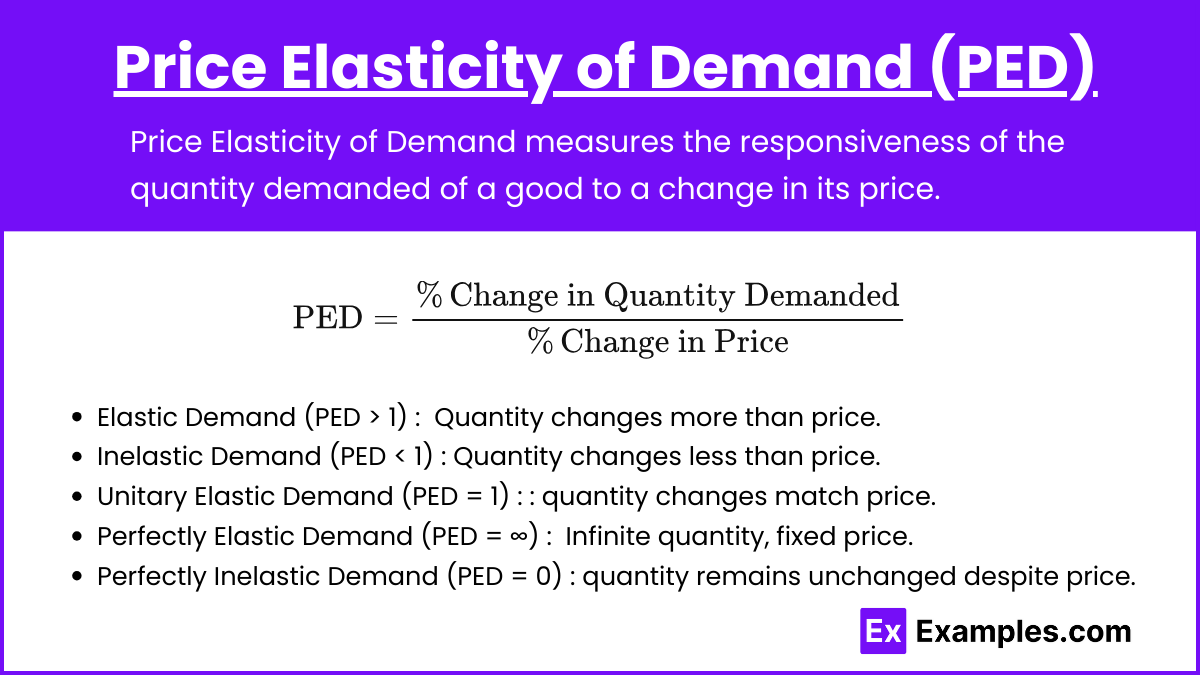

Definition: Price Elasticity of Demand measures the responsiveness of the quantity demanded of a good to a change in its price.

Formula:

Interpretation:

Elastic Demand (PED > 1): Quantity demanded changes by a larger percentage than the price change.

Inelastic Demand (PED < 1): Quantity demanded changes by a smaller percentage than the price change.

Unitary Elastic Demand (PED = 1): Quantity demanded changes by exactly the same percentage as the price change.

Perfectly Elastic Demand (PED = ∞): Consumers are willing to buy any quantity at a specific price but none at any other price.

Perfectly Inelastic Demand (PED = 0): Quantity demanded does not change regardless of price changes.

Examples:

Elastic Demand: Luxury goods, non-essential items (e.g., high-end electronics).

Inelastic Demand: Necessities (e.g., insulin for diabetics, basic food items).

2. Price Elasticity of Supply (PES)

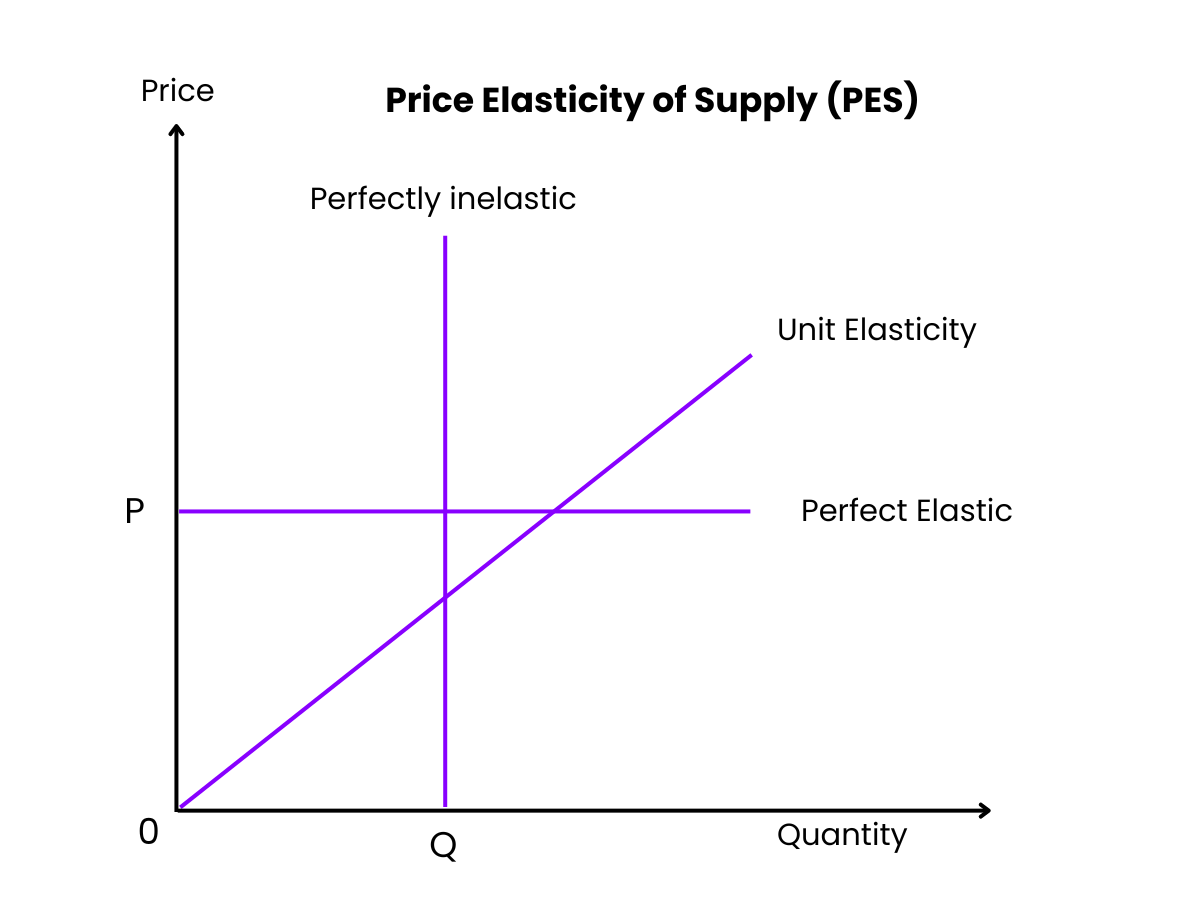

Definition: Price Elasticity of Supply measures the responsiveness of the quantity supplied of a good to a change in its price.

Formula:

Interpretation:

Elastic Supply (PES > 1): Quantity supplied changes by a larger percentage than the price change.

Inelastic Supply (PES < 1): Quantity supplied changes by a smaller percentage than the price change.

Unitary Elastic Supply (PES = 1): Quantity supplied changes by exactly the same percentage as the price change.

Perfectly Elastic Supply (PES = ∞): Producers are willing to supply any quantity at a specific price.

Perfectly Inelastic Supply (PES = 0): Quantity supplied does not change regardless of price changes.

Factors Influencing PES:

Time Horizon: Supply is more elastic in the long run.

Flexibility of Production: Easier to switch production increases elasticity.

Availability of Inputs: Readily available inputs make supply more elastic.

3. Income Elasticity of Demand (YED)

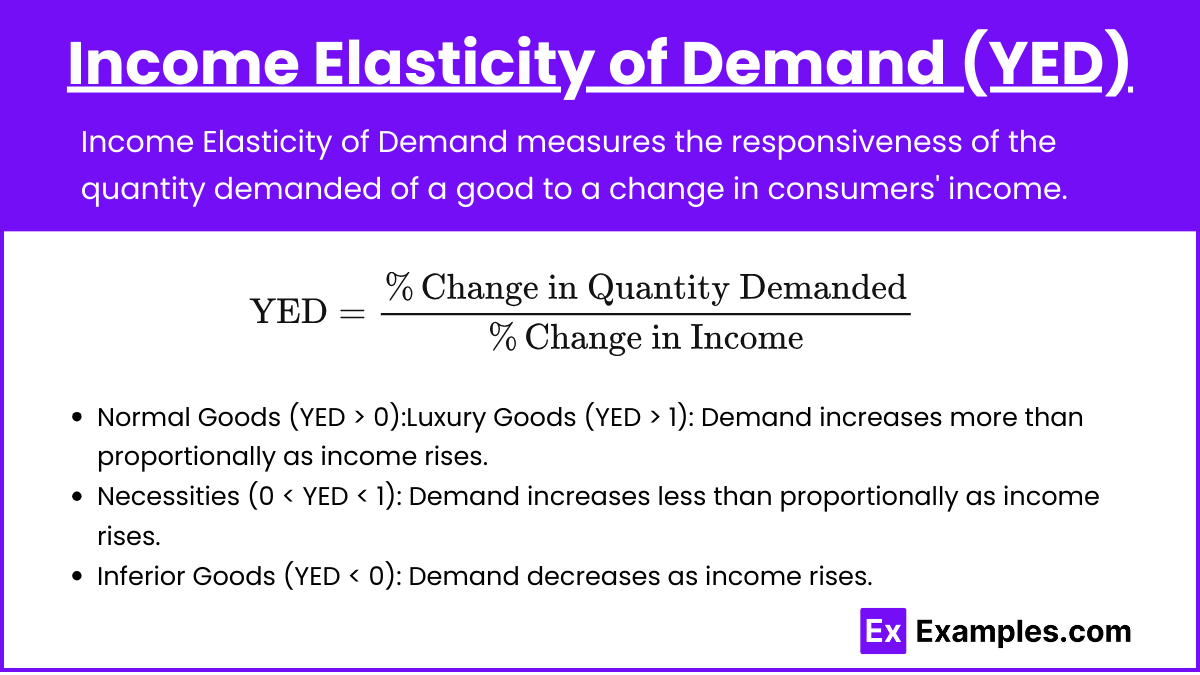

Definition: Income Elasticity of Demand measures the responsiveness of the quantity demanded of a good to a change in consumers' income.

Formula:

Interpretation:

Normal Goods (YED > 0):

Luxury Goods (YED > 1): Demand increases more than proportionally as income rises.

Necessities (0 < YED < 1): Demand increases less than proportionally as income rises.

Inferior Goods (YED < 0): Demand decreases as income rises.

Examples:

Luxury Good: High-end cars, fine dining.

Necessity: Basic food items, utilities.

Inferior Good: Generic brands, used cars.

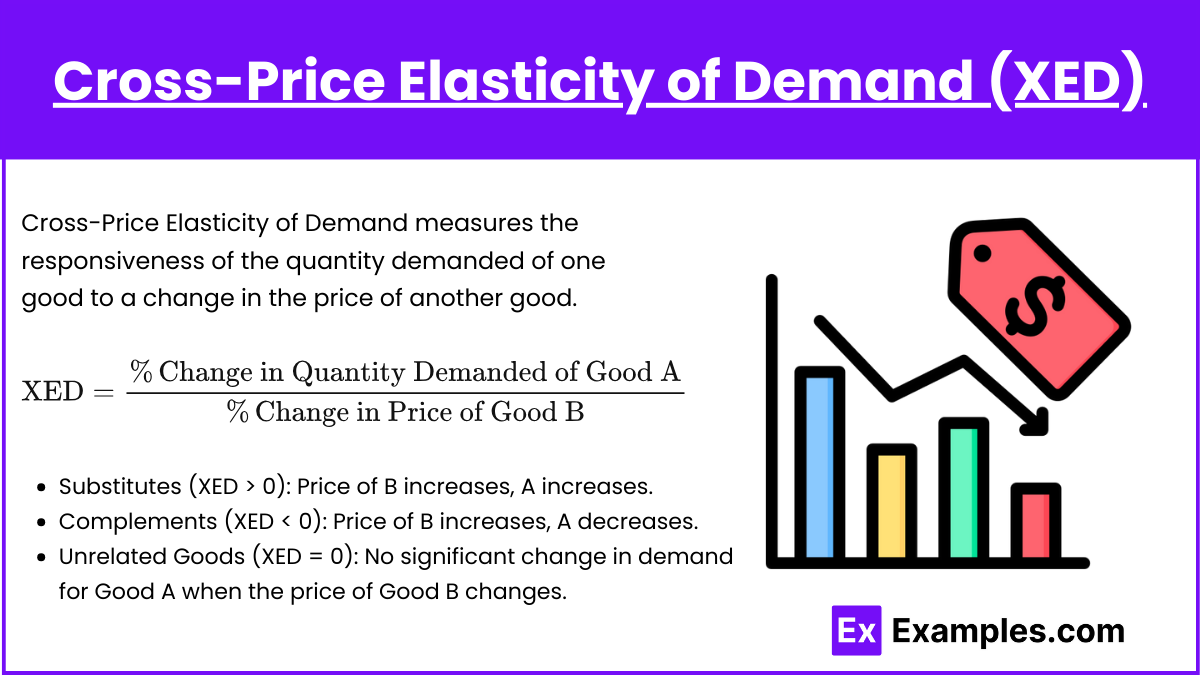

4. Cross-Price Elasticity of Demand (XED)

Definition: Cross-Price Elasticity of Demand measures the responsiveness of the quantity demanded of one good to a change in the price of another good.

Formula:

Interpretation:

Substitutes (XED > 0): An increase in the price of Good B leads to an increase in demand for Good A.

Complements (XED < 0): An increase in the price of Good B leads to a decrease in demand for Good A.

Unrelated Goods (XED = 0): No significant change in demand for Good A when the price of Good B changes.

Examples:

Substitutes: Tea and coffee; butter and margarine.

Complements: Printers and ink cartridges; smartphones and apps.

Importance of Elasticity in Economics

Tax Incidence and Elasticity: The elasticity of demand and supply determines how the burden of a tax is shared between consumers and producers. If demand is inelastic and supply is elastic, consumers bear most of the tax burden. If demand is elastic and supply is inelastic, producers bear more of the tax burden.

Revenue Implications for Firms: Understanding elasticity helps firms set prices optimally. For goods with inelastic demand, increasing prices can increase revenue since consumers are less responsive to price changes. For goods with elastic demand, raising prices may reduce revenue, as consumers will cut back on consumption.

Price Controls and Elasticity: Governments often impose price ceilings (maximum prices) or price floors (minimum prices) on goods. Elasticity helps predict the consequences of these controls. For example, if rent controls (price ceilings on housing) are imposed in a market with elastic supply, it can lead to housing shortages.

Elasticity and Efficiency: Elasticity measures play a crucial role in evaluating the efficiency of markets. When demand or supply is highly elastic, markets are more responsive to changes in prices and policies, which can influence decisions about subsidies, tariffs, and regulations.

Examples

Example 1. Price Elasticity of Demand: Luxury vs. Necessity Goods

Example: Consider the market for luxury sports cars compared to basic household necessities like bread.

Explanation: Luxury sports cars typically have a high price elasticity of demand (PED) because they are non-essential and have many substitutes. If the price of a luxury sports car increases, consumers are likely to reduce their quantity demanded significantly or opt for alternative luxury vehicles. Conversely, basic necessities like bread usually exhibit inelastic demand (PED < 1) because they are essential for daily life. Even if the price of bread rises, consumers will continue to purchase it in similar quantities, as there are few substitutes that fulfill the same need. This distinction helps businesses and policymakers understand how different products respond to price changes and make informed decisions accordingly.

Example 2. Income Elasticity of Demand: Normal vs. Inferior Goods

Example: Analyzing the demand for organic vegetables versus instant noodles as consumer incomes change.

Explanation: Organic vegetables are considered normal goods with a positive income elasticity of demand (YED > 0). As consumers' incomes increase, they tend to purchase more organic vegetables because they perceive them as higher quality and are willing to spend more on healthier food options. On the other hand, instant noodles are often classified as inferior goods (YED < 0). When consumers experience an increase in income, they may decrease their consumption of instant noodles in favor of more nutritious or premium food items. This example highlights how changes in income levels can differentially impact the demand for various types of goods, influencing producers' strategies and market dynamics.

Example 3. Cross-Price Elasticity of Demand: Substitutes and Complements

Example: The relationship between coffee and tea, and between printers and ink cartridges.

Explanation: Coffee and tea are substitute goods with a positive cross-price elasticity of demand (XED > 0). If the price of coffee rises, consumers may switch to tea, increasing the demand for tea as a substitute. Conversely, printers and ink cartridges are complementary goods with a negative cross-price elasticity of demand (XED < 0). If the price of printers decreases, the demand for ink cartridges is likely to increase because more people are buying printers that require ink. These relationships illustrate how the price changes of one good can affect the demand for another, providing insights into market interdependencies and helping businesses anticipate changes in consumer behavior.

Example 4. Price Elasticity of Supply: Agricultural Products vs. Manufactured Goods

Example: Comparing the supply elasticity of wheat versus smartphones.

Explanation: Agricultural products like wheat typically have an inelastic supply in the short run (PES < 1) because farmers cannot quickly adjust the quantity produced due to factors like growing seasons and limited arable land. If the price of wheat increases, the quantity supplied will rise, but not proportionately. In contrast, manufactured goods like smartphones often have a more elastic supply (PES > 1) because producers can scale up production more easily in response to price changes by utilizing flexible manufacturing processes and technology. This example demonstrates how different industries respond to price changes based on their ability to adjust production levels, influencing market supply dynamics and pricing strategies.

Example 5. Tax Incidence and Elasticity: Who Bears the Burden?

Example: Imposing a tax on cigarettes and analyzing the burden between consumers and producers.

Explanation: When the government imposes a tax on cigarettes, the incidence of the tax—i.e., who bears the burden—depends on the relative elasticities of demand and supply. Cigarettes typically have inelastic demand (PED < 1) because they are addictive, and consumers are less sensitive to price changes. The supply of cigarettes may also be relatively inelastic in the short term. Given these inelasticities, both consumers and producers will share the tax burden, but consumers will bear a larger portion since their demand does not decrease significantly with higher prices. This example illustrates how understanding the elasticities of demand and supply is crucial for predicting the effects of taxation and designing policies that achieve desired economic outcomes.

Multiple Choice Questions

Question 1

If the price elasticity of demand for a product is 2.5, what does this imply about the demand for the product?

A) Demand is inelastic

B) Demand is unit elastic

C) Demand is elastic

D) The product is a necessity

Answer: C) Demand is elastic

Explanation: Price elasticity of demand (PED) measures the responsiveness of quantity demanded to a change in price. A PED greater than 1 indicates that demand is elastic, meaning that the quantity demanded changes by a larger percentage than the change in price. In this case, a price elasticity of 2.5 means that a 1% increase in price would result in a 2.5% decrease in quantity demanded, making the demand elastic. The other options are incorrect because:

A) Inelastic demand has a PED of less than 1.

B) Unit elastic demand has a PED equal to 1.

D) Necessities often have inelastic demand (PED < 1), which is not the case here.

Question 2

Which of the following goods is most likely to have inelastic demand?

A) Luxury cars

B) Salt

C) Designer clothes

D) Airline tickets

Answer: B) Salt

Explanation: Goods with inelastic demand are those where a change in price has little effect on the quantity demanded. Salt is an everyday necessity, and even if the price increases, consumers will still buy it in almost the same quantities because it has few substitutes and represents a small portion of a consumer’s budget. The other goods are likely to have more elastic demand because:

A) Luxury cars are discretionary items, and consumers are sensitive to price changes.

C) Designer clothes are luxury items, meaning demand is more elastic as consumers can choose not to purchase them or switch to substitutes.

D) Airline tickets can be sensitive to price changes, especially when alternatives like driving or choosing different travel times are available.

Question 3

If the cross-price elasticity of demand (XED) between two goods is negative, what does this imply about the relationship between the two goods?

A) They are substitutes

B) They are complements

C) They are unrelated goods

D) They are normal goods

Answer: B) They are complements

Explanation: Cross-price elasticity of demand (XED) measures how the quantity demanded of one good responds to a change in the price of another good. A negative XED means that an increase in the price of one good leads to a decrease in the demand for the other, indicating that the two goods are complements. For example, if the price of printers increases, the demand for ink cartridges may decrease because the two are used together. The other options are incorrect because:

A) Substitute goods have a positive XED, where an increase in the price of one good leads to an increase in the demand for the other.

C) Unrelated goods would have an XED close to zero.

D) Normal goods are associated with income elasticity, not cross-price elasticity.