Oligopoly and Game Theory are pivotal topics in AP Microeconomics, illustrating how a few dominant firms interact strategically within a market. An oligopoly is characterized by limited competition, where each firm’s decisions on pricing and output significantly impact rivals. Game Theory complements this by providing a framework to analyze these strategic interactions, predicting outcomes like price wars or collusion. Mastering these concepts is essential for understanding real-world market behaviors and excelling in the AP Microeconomics exam.

Free AP Microeconomics Practice Test

Learning Objectives

By studying "Oligopoly and Game Theory" for AP Microeconomics, you should understand the defining characteristics of oligopolistic markets, including few dominant firms and significant barriers to entry. Master the key models of oligopoly behavior, such as Cournot, Bertrand, and Stackelberg, and analyze the kinked demand curve’s role in price rigidity. Grasp essential game theory concepts like Nash Equilibrium, dominant strategies, and the Prisoner’s Dilemma. Additionally, evaluate real-world applications of collusion, cartels, and non-price competition strategies used by firms in oligopolistic markets.

1. Definition of Oligopoly

Oligopoly is a market structure where a few large firms dominate the industry, influencing prices and output, with significant barriers to entry and limited competition.

Few Large Firms: The market is dominated by a small number of firms, each holding a substantial market share.

Interdependence: Firms are mutually interdependent; each firm's actions affect and are affected by the actions of other firms.

Barriers to Entry: Significant barriers prevent new firms from entering the market easily, such as high startup costs, patents, or strong brand identities.

Product Differentiation or Homogeneity: Products may be homogeneous (e.g., steel, oil) or differentiated (e.g., automobiles, smartphones).

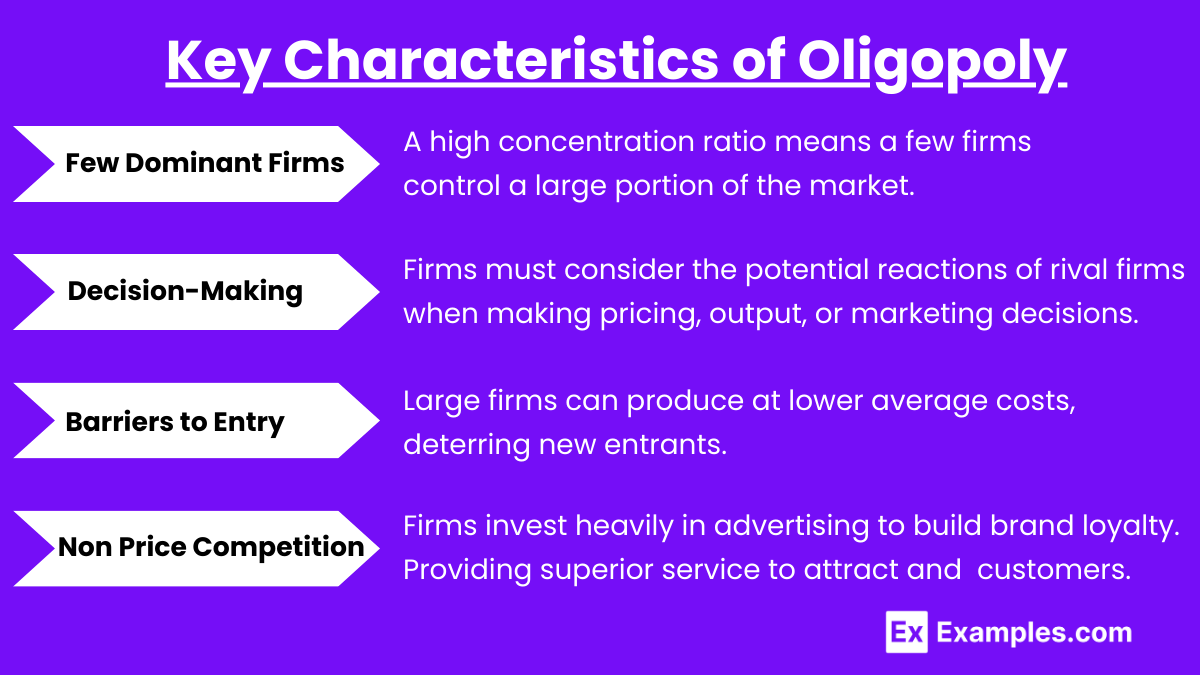

2. Key Characteristics of Oligopoly

a. Few Dominant Firms

Market Concentration: A high concentration ratio means a few firms control a large portion of the market.

Examples: The automobile industry (e.g., Toyota, Ford, Volkswagen), the smartphone market (e.g., Apple, Samsung), and the airline industry.

b. Interdependence

Strategic Decision-Making: Firms must consider the potential reactions of rival firms when making pricing, output, or marketing decisions.

Kinked Demand Curve: Suggests that firms may face different demand elasticity based on whether they raise or lower prices, leading to price rigidity.

c. Barriers to Entry

Economies of Scale: Large firms can produce at lower average costs, deterring new entrants.

Control of Resources: Ownership of essential resources or technology.

Government Policies: Regulations, licenses, and patents that restrict entry.

d. Non-Price Competition

Advertising and Marketing: Firms invest heavily in advertising to build brand loyalty.

Product Differentiation: Enhancing product features, quality, and design to distinguish from competitors.

Customer Service: Providing superior service to attract and retain customers.

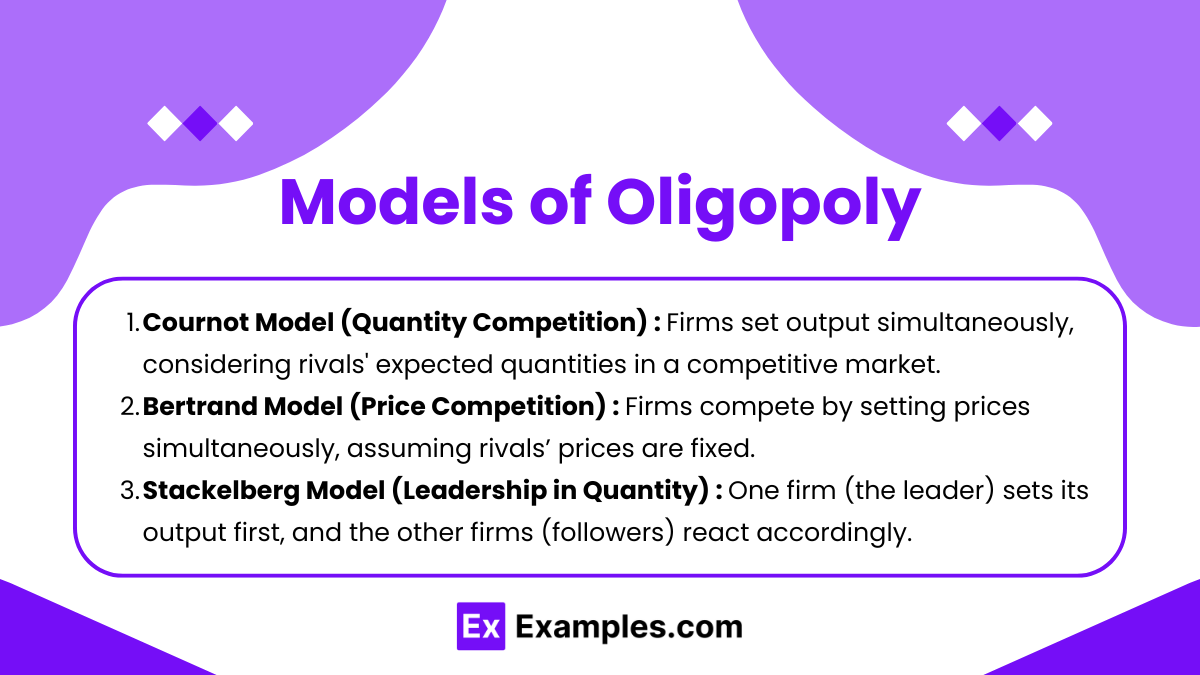

3. Models of Oligopoly

Oligopoly models help explain how firms behave in an oligopolistic market. The most prominent models include:

a. Cournot Model (Quantity Competition)

Assumption: Firms choose output levels simultaneously, and each firm decides its quantity based on the expected quantity of rivals.

Equilibrium: Cournot-Nash Equilibrium occurs when no firm can increase profit by unilaterally changing its output.

Key Points:

Each firm’s output decision affects the market price.

The total output is higher than in monopoly but lower than in perfect competition.

Firms earn positive economic profits in the short run; profits may normalize in the long run if entry is possible.

b. Bertrand Model (Price Competition)

Assumption: Firms compete by setting prices simultaneously, assuming rivals’ prices are fixed.

Equilibrium: Firms reach a Nash Equilibrium where both set prices equal to marginal cost, leading to outcomes similar to perfect competition.

Key Points:

Even with few firms, price competition can drive prices down to marginal cost.

Less applicable when products are differentiated or firms have capacity constraints.

c. Stackelberg Model (Leadership in Quantity)

Assumption: One firm (the leader) sets its output first, and the other firms (followers) react accordingly.

Equilibrium: The leader firm can achieve a higher profit by committing to an output level that influences follower firms.

Key Points:

Strategic advantage for the leader.

Results in higher total output and lower price compared to the Cournot model.

d. Kinked Demand Curve Model

Assumption: Firms believe that if they raise prices, rivals will not follow, leading to a loss of market share; if they lower prices, rivals will follow, preventing gain in market share.

Equilibrium: Price rigidity; firms are reluctant to change prices because of asymmetric reactions from competitors.

Key Points:

Explains why prices in oligopolistic markets tend to be stable.

Leads to a kink in the demand curve, resulting in a discontinuous marginal revenue curve.

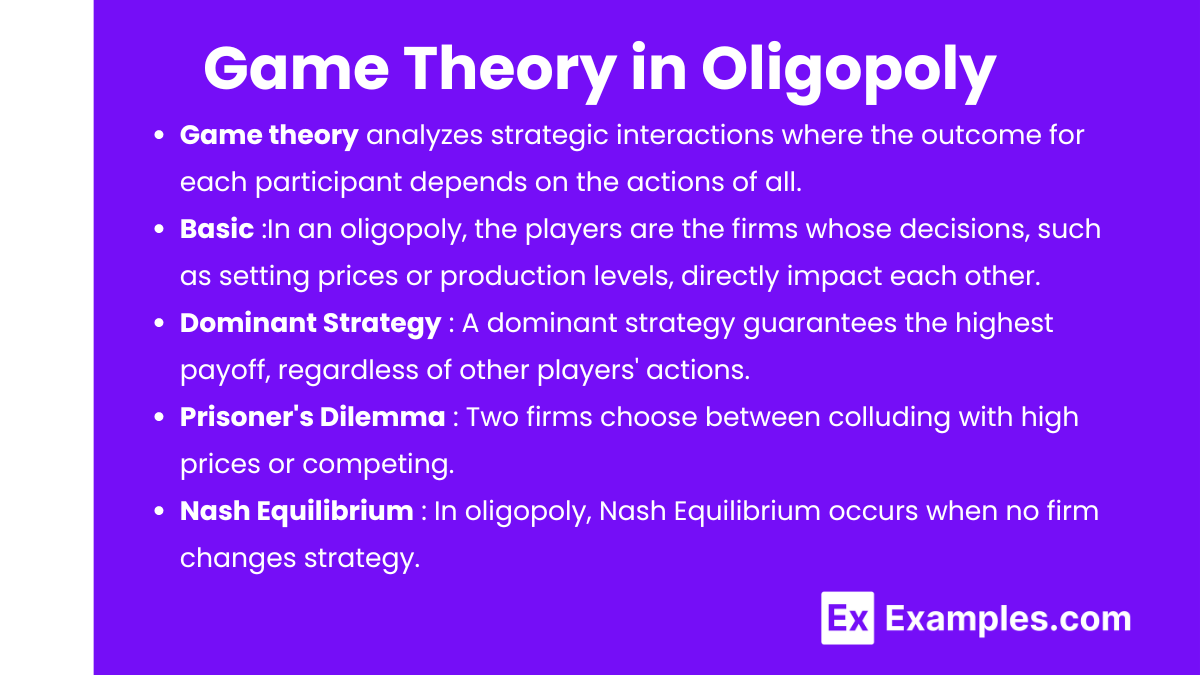

4. Game Theory in Oligopoly

Game theory analyzes strategic interactions where the outcome for each participant depends on the actions of all. In oligopoly, game theory helps predict firms’ behavior regarding pricing, output, and other strategic decisions.

a. Basic Concepts

In an oligopoly, the players are the firms whose decisions, such as setting prices or production levels, directly impact each other. These firms have various strategies they can adopt, such as setting high or low prices, and the combination of these strategies determines their payoffs, which are the resulting profits or losses.

Players: The firms in the oligopoly.

Strategies: The possible actions each firm can take (e.g., set high price or low price).

Payoffs: The profits resulting from the combination of strategies chosen by the firms.

Nash Equilibrium: A set of strategies where no player can benefit by unilaterally changing their strategy.

b. Dominant Strategy

A dominant strategy is an action that provides a firm or player with the highest payoff, regardless of the decisions made by other players. It guarantees the best outcome for the firm, no matter what strategies competitors choose.

Definition: A strategy that yields a higher payoff regardless of what the other players do.

Example: In the Prisoner's Dilemma, betraying is the dominant strategy for both players.

c. Prisoner's Dilemma

In this scenario, two firms in an oligopoly must independently choose whether to collude by setting high prices or compete by setting low prices. If both firms collude, they earn moderate profits.

Scenario: Two firms must decide independently whether to collude (e.g., set high prices) or compete (e.g., set low prices).

Payoffs:

Both Collude: Moderate profits.

One Colludes, One Competes: The competitor gains a larger market share, higher profit; the colluder suffers.

Both Compete: Low profits due to price wars.

Outcome: Both firms choose to compete, leading to lower profits than if they had colluded.

Implications: Demonstrates the difficulty of sustaining collusion in oligopoly.

d. Nash Equilibrium in Oligopoly

In an oligopoly, Nash Equilibrium occurs when each firm selects the best possible strategy, assuming that the other firms do not change theirs.

Example: In the Cournot model, each firm’s output decision is the best response to the output of the other firm.

Significance: Predicts stable outcomes where firms have no incentive to deviate unilaterally.

e. Collusion and Cartels

Collusion occurs when firms in an oligopoly cooperate to set prices or output levels in order to maximize their joint profits. This behavior is often illegal due to anti-trust laws aimed at promoting competition, though some cartels, like OPEC, are legal.

Definition: Firms cooperate to set prices or output to maximize joint profits.

Legality: Often illegal due to anti-trust laws (e.g., OPEC as a legal cartel).

Challenges:

Incentive to Cheat: Individual firms can benefit by secretly undercutting cartel agreements.

Monitoring: Difficult to enforce agreements without external enforcement.

Examples

Example 1. The Airline Industry

The airline industry is a quintessential example of an oligopoly, characterized by a few major carriers that dominate the market. Companies like Delta, American Airlines, and United Airlines control a significant share of both domestic and international flights. These firms are highly interdependent; the pricing, routes, and services offered by one airline directly influence the strategies of the others.

Game Theory Application: When one airline decides to reduce ticket prices on a particular route to attract more passengers, rival airlines often respond by matching the price cuts to maintain their market share. This scenario exemplifies the Prisoner's Dilemma, where each airline faces the choice to either compete (lower prices) or collude (maintain higher prices). Although collusion could lead to higher profits for all, the fear of being undercut by a competitor often drives firms to compete aggressively, resulting in lower profits for everyone involved.

Example 2. The Smartphone Market

The smartphone market is dominated by a few key players, including Apple, Samsung, and Huawei. These companies engage in fierce competition to innovate and capture consumer preferences through differentiated products. Each firm's decisions regarding pricing, features, and marketing strategies significantly impact the others.

Game Theory Application: In the context of the Bertrand Model of price competition, if Apple introduces a new smartphone with advanced features at a premium price, Samsung might respond by either matching the price to compete directly or introducing its own innovative features at a slightly lower price to attract more customers. The strategic decision-making process here involves anticipating competitors' reactions and adjusting strategies accordingly to achieve a Nash Equilibrium, where no firm can improve its profit by unilaterally changing its price or features.

Example 3. The Oil Market

The global oil market is another classic example of an oligopoly, with major players like ExxonMobil, Chevron, BP, and Shell controlling a large portion of oil production and distribution. These firms often engage in strategic planning to influence oil prices and maximize profits.

Game Theory Application: The Cournot Model of quantity competition can be applied here. If ExxonMobil decides to increase oil production to capitalize on high demand, rival firms like Chevron and Shell must decide whether to also increase production, potentially leading to a surplus and lower prices, or to maintain their production levels to keep prices stable. The interdependent nature of these decisions highlights the strategic considerations firms must undertake to reach an equilibrium where each firm's output decision is the best response to the others'.

Example 4. The Automobile Industry

The automobile industry is dominated by a few large manufacturers such as Toyota, Volkswagen, Ford, and General Motors. These firms compete on various fronts, including price, quality, technology, and marketing to gain a competitive edge in the market.

Game Theory Application: Consider the scenario of introducing electric vehicles (EVs). If Toyota invests heavily in EV technology and marketing, Volkswagen and Ford might respond by accelerating their own EV development to avoid losing market share. This strategic interaction can be analyzed using the Stackelberg Model, where one firm (the leader) makes a significant investment or innovation, and the follower firms adjust their strategies in response. The leader gains a competitive advantage by setting industry standards, while follower firms strive to catch up, leading to an equilibrium where each firm's actions are optimized based on the anticipated responses of others.

Example 5. The Beverage Industry: Coca-Cola vs. Pepsi

The rivalry between Coca-Cola and Pepsi is a textbook example of oligopolistic competition combined with game theory strategies. These two giants dominate the soft drink market and continuously engage in competitive strategies to outperform each other.

Game Theory Application: One common strategic interaction is advertising expenditure. If Coca-Cola decides to launch a massive advertising campaign to boost its brand image, Pepsi must decide whether to increase its own advertising to maintain its market position or conserve resources. This scenario can be modeled using a Game Theory Payoff Matrix, where each firm’s payoff depends on the combination of strategies chosen by both. The firms aim to reach a Nash Equilibrium where neither can improve its payoff by changing its strategy unilaterally, leading to a balance in advertising spending that sustains their competitive positions without engaging in a costly advertising war.

Multiple Choice Questions

Question 1

Which of the following best illustrates the concept of a Nash Equilibrium in an oligopolistic market?

A) Both firms decide to collude and set high prices to maximize joint profits.

B) One firm sets a high price while the other sets a low price to gain a larger market share.

C) Both firms choose to set prices based on the expectation that the other firm will not change its price, resulting in stable pricing.

D) Firms repeatedly change prices to undercut each other, leading to a price war.

Answer: C) Both firms choose to set prices based on the expectation that the other firm will not change its price, resulting in stable pricing.Explanation:

Nash Equilibrium occurs when each firm in a game chooses the best possible strategy, taking into account the strategies chosen by other firms. In the context of an oligopoly:

Option A: Collusion to set high prices is not a Nash Equilibrium because each firm has an incentive to deviate and set a lower price to gain more market share, undermining the collusion.

Option B: If one firm sets a high price while the other sets a low price, the firm with the low price can increase its profit by further undercutting, meaning this scenario is not stable and does not represent a Nash Equilibrium.

Option C: Both firms setting stable prices, expecting the other not to change, represents a Nash Equilibrium. Neither firm can improve its profit by unilaterally changing its price, assuming the other firm's price remains constant.

Option D: A price war involves both firms continuously changing prices to undercut each other, which is unstable and does not constitute a Nash Equilibrium.

Thus, Option C correctly captures the essence of Nash Equilibrium in an oligopolistic setting where firms' strategies stabilize based on mutual expectations.

Question 2

In the Prisoner's Dilemma model applied to an oligopoly, why might firms choose to compete rather than collude, even though collusion would lead to higher joint profits?

A) Firms are legally prohibited from colluding, so they have no choice but to compete.

B) Each firm fears that the other will cheat on the collusive agreement to gain a larger market share.

C) Competing allows firms to maximize their individual profits without regard to rivals.

D) Collusion leads to lower prices, which reduces overall profits for all firms involved.

Answer: B) Each firm fears that the other will cheat on the collusive agreement to gain a larger market share.Explanation:

The Prisoner's Dilemma in game theory illustrates a situation where two firms would benefit more from cooperating (colluding) but are likely to act in their own self-interest, leading to worse outcomes for both.

Option A: While legal prohibitions against collusion (like anti-trust laws) can prevent firms from colluding, the Prisoner's Dilemma specifically addresses the strategic decision-making aspect, not just legal constraints.

Option B: Correct. In the Prisoner's Dilemma, each firm is uncertain whether the other will stick to the collusive agreement. The fear that the rival will cheat (e.g., by lowering prices or increasing output) to gain a larger market share leads each firm to choose to compete instead of collude, even though mutual collusion would yield higher joint profits.

Option C: While competing may allow firms to maximize their individual profits, the key reason in the Prisoner's Dilemma is the fear of the other firm's betrayal, not just the pursuit of individual profits.

Option D: Collusion typically involves agreeing to set higher prices to increase joint profits, not lower prices. Lower prices would be associated with competition, not collusion.

Therefore, Option B correctly identifies the strategic fear of being betrayed by the rival, which drives firms to compete rather than collude, aligning with the core insight of the Prisoner's Dilemma.

Question 3

According to the Kinked Demand Curve model, why do prices tend to remain stable in an oligopolistic market despite changes in marginal costs?

A) Firms in an oligopoly have no control over their pricing decisions due to perfect competition.

B) Firms believe that if they raise prices, rivals will not follow, but if they lower prices, rivals will match the decrease, leading to a kink in the demand curve.

C) Government regulations enforce price stability to prevent price wars among oligopolistic firms.

D) Firms operate under a collusive agreement to maintain fixed prices and avoid competition.

Answer: B) Firms believe that if they raise prices, rivals will not follow, but if they lower prices, rivals will match the decrease, leading to a kink in the demand curve.

Explanation:

The Kinked Demand Curve model explains price rigidity in oligopolistic markets through the expectations firms have about their rivals' reactions to price changes.

Option A: Incorrect. Oligopolistic firms do have some control over pricing, unlike in perfect competition where firms are price takers.

Option B: Correct. The Kinked Demand Curve model posits that firms in an oligopoly expect that:

If they raise prices, rivals will not follow, leading to a loss of market share because consumers will switch to the cheaper alternatives offered by competitors.

If they lower prices, rivals will match the decrease to maintain their market shares, leading to a price war where no firm gains significant advantage.

This asymmetry creates a "kink" in the demand curve at the current price level, making the marginal revenue curve discontinuous. As a result, even if marginal costs change, the price remains stable because the firm does not find it profitable to change prices due to the expected reactions of rivals.

Option C: While government regulations can influence pricing, the Kinked Demand Curve model specifically explains price stability through firms' strategic expectations, not through external enforcement.

Option D: The model does not rely on actual collusive agreements but on the expectation of rival behavior. Firms may implicitly avoid price changes to maintain stability without formal agreements.

Thus, Option B accurately captures the rationale behind price stability in the Kinked Demand Curve model within oligopolistic markets.