Evaluating the evidence an author uses to support their argument is a crucial skill in critical reading and analysis, especially for the AP Seminar exam. This process involves assessing the relevance, credibility, accuracy, sufficiency, and timeliness of the evidence presented. By critically examining these aspects, students can determine the strength and validity of an author’s claims. Effective evaluation of evidence not only enhances understanding of the argument but also strengthens the student’s ability to construct well-supported arguments, engage in informed discussions, and excel in academic writing and research.

Learning Objectives

Learn to identify and understand different types of evidence, assessing their relevance and credibility, and verifying accuracy and sufficiency. Understand how to apply structured evaluation criteria, such as the CRAAP test, and critical thinking techniques like the SIFT method. Learn to critically analyze arguments by evaluating the evidence used to support them, identifying logical strengths and weaknesses. Mastery of these skills will enhance your ability to develop well-supported, persuasive arguments in academic writing, preparing you for success in the AP Seminar exam.

Understanding Evidence

What is Evidence?

Evidence refers to the information, data, or facts an author uses to support their reasons and ultimately their central claim. It can take various forms, including:

- Statistics: Numerical data that support the argument.

- Expert Testimony: Opinions or findings from credible authorities or experts in the field.

- Research Studies: Data and conclusions from scientific research.

- Anecdotes: Short personal stories or examples.

- Historical Facts: Events or facts from history that support the argument.

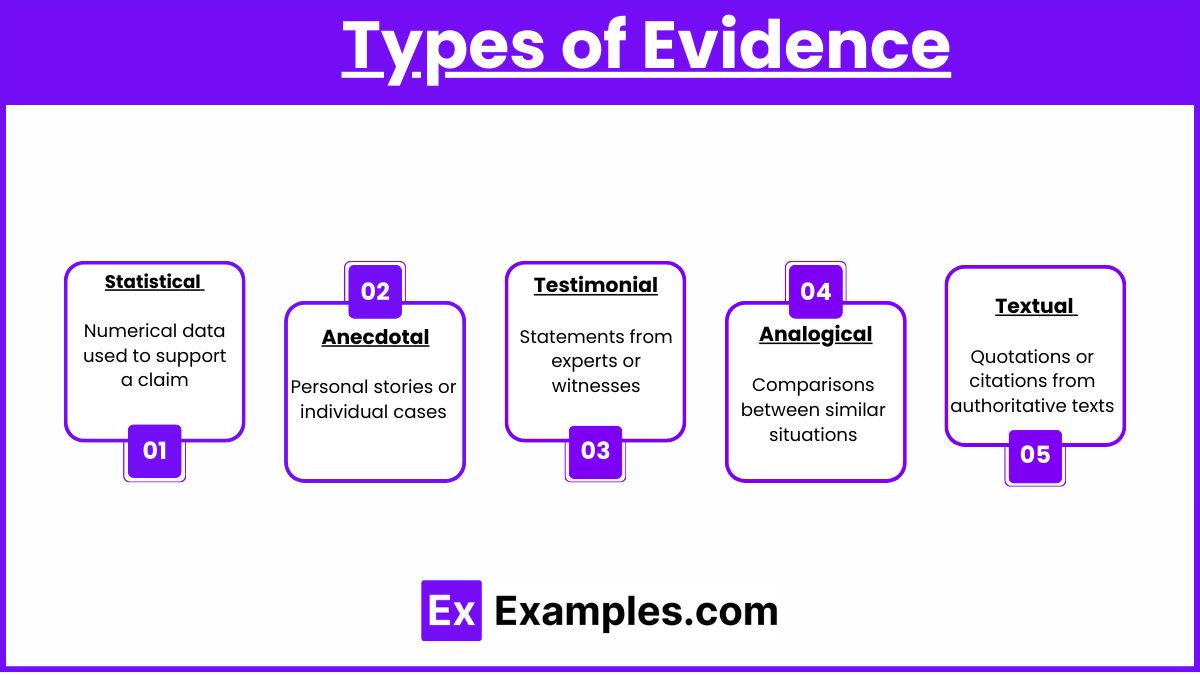

Types of Evidence

- Statistical Evidence:

- Numerical data used to support a claim.

- Example: “According to the CDC, the vaccination rate increased by 15% in the past year.”

- Anecdotal Evidence:

- Personal stories or individual cases.

- Example: “A patient reported significant improvement in symptoms after using the new medication.”

- Testimonial Evidence:

- Statements from experts or witnesses.

- Example: “Dr. Smith, a leading cardiologist, stated that regular exercise reduces heart disease risk.”

- Analogical Evidence:

- Comparisons between similar situations.

- Example: “Just as seat belts improve car safety, helmets enhance cyclist safety.”

- Textual Evidence:

- Quotations or citations from authoritative texts.

- Example: “The Constitution states, ‘We the people…’ which underscores democratic principles.”

Criteria for Evaluating Evidence

- Relevance:

- Definition: The evidence must directly support the claim.

- Example: In an argument about climate change, relevant evidence might include data on global temperature trends, not unrelated economic statistics.

- Credibility:

- Definition: The evidence must come from a reliable and authoritative source.

- Example: Peer-reviewed journal articles, official government reports, and expert testimonies are generally credible sources.

- Accuracy:

- Definition: The evidence must be correct and free from errors.

- Example: Verifying the accuracy of statistical data by cross-referencing with original studies or official records.

- Sufficiency:

- Definition: There must be enough evidence to convincingly support the claim.

- Example: One anecdotal story is not sufficient to prove a widespread trend; multiple cases and statistical data provide stronger support.

- Timeliness:

- Definition: The evidence must be current and relevant to the time period in question.

- Example: Using outdated data might weaken an argument about present-day issues.

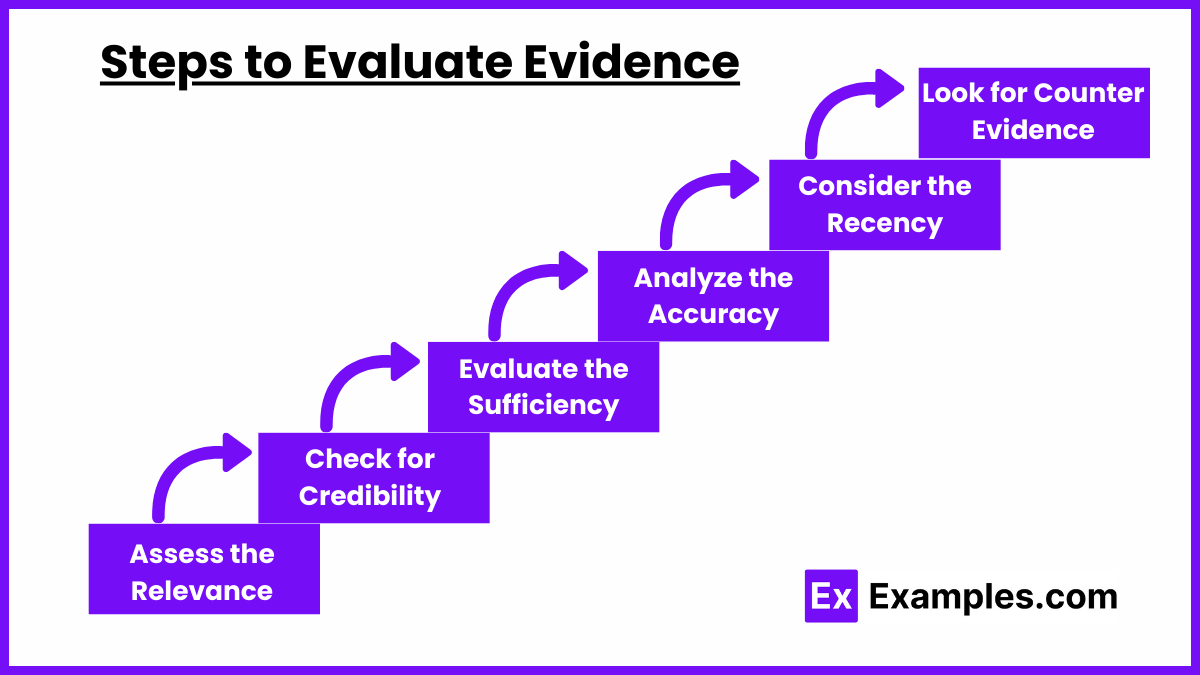

Steps to Evaluate Evidence

1. Assess the Relevance

Determine if the evidence directly supports the claim or reason. Relevant evidence should be closely related to the argument and help to establish its validity.

Example:

- Claim: Increased screen time negatively affects children’s health.

- Evidence: A study showing a correlation between high screen time and increased obesity rates in children.

2. Check for Credibility

Evaluate the credibility of the evidence by considering the source. Credible evidence comes from reputable, reliable, and unbiased sources.

Factors to consider:

- Author’s credentials: Is the author an expert in the field?

- Publication source: Is the evidence from a peer-reviewed journal, a reputable news outlet, or an authoritative organization?

- Bias: Is there any indication of bias or a conflict of interest?

3. Evaluate the Sufficiency

Examine if there is enough evidence to convincingly support the claim. The evidence should be adequate in quantity and depth to substantiate the argument.

Example:

- Insufficient Evidence: One anecdote or a single study with a small sample size.

- Sufficient Evidence: Multiple studies with large sample sizes, meta-analyses, or comprehensive reviews.

4. Analyze the Accuracy

Ensure the evidence is accurate and correctly interpreted. Misinterpretation or manipulation of data can undermine the argument.

Steps to check accuracy:

- Verify the data by cross-referencing with other sources.

- Check for any logical fallacies or misrepresentations.

5. Consider the Recency

Evaluate the timeliness of the evidence. Recent evidence is often more relevant, especially in fields that rapidly evolve, such as technology and medicine.

Example:

- Outdated Evidence: A study from the 1990s on internet usage patterns.

- Recent Evidence: A study from the last five years on current internet usage trends.

6. Look for Counter-Evidence

Identify if the author has addressed counter-evidence or opposing viewpoints. A strong argument acknowledges and refutes counter-evidence effectively.

Example:

- Counter-Evidence: Research suggesting moderate screen time has educational benefits.

- Rebuttal: The author might argue that the negative health impacts outweigh these benefits.