Analysis of Financial Institutions provides a comprehensive understanding of the unique aspects of banking, insurance, and investment firms. This topic explores the distinct financial statements, regulatory environments, and risk factors associated with financial institutions. Focus is placed on assessing credit risk, liquidity, capital adequacy, and profitability, along with the impact of economic conditions on financial stability. Mastery of these elements is essential for evaluating the performance, resilience, and valuation of financial institutions, forming a critical component of financial analysis and investment decision-making.

Learning Objectives

In studying "Analysis of Financial Institutions" for the CFA, you should learn to evaluate the unique financial statements and metrics used to assess banks, insurance companies, and investment firms. Understand the distinctive asset, liability, and equity structures of these institutions, including the impact of regulatory requirements on capital and liquidity. Analyze key performance indicators such as net interest margin, loan loss provisions, and underwriting profit, focusing on their influence on profitability and risk. Assess the role of financial ratios specific to these institutions in determining financial health and risk exposure. Additionally, understand how economic and market factors affect financial institutions' operations and profitability, aiding in comprehensive risk analysis and valuation.

Evaluating Financial Statements and Metrics for Financial Institutions

Financial institutions, including banks, insurance companies, and investment firms, have unique financial statements and metrics compared to non-financial companies. Their financial analysis requires a focus on key areas such as asset quality, liquidity, capital adequacy, and profitability. Understanding these metrics is essential for assessing their financial health, stability, and performance.

Unique Aspects of Financial Institution Financial Statements

Financial statements for financial institutions include distinctive line items and metrics related to their primary business of lending, investing, and managing financial risk.

Balance Sheet

Assets: Primarily consists of loans, investment securities, cash, and interbank deposits. Loans and investment securities generate interest income and represent the majority of assets.

Liabilities: Deposits, borrowings, and other debt make up the bulk of liabilities. Deposits are often the largest funding source, with short- and long-term borrowings supporting additional funding needs.

Equity: Capital adequacy is critical for financial institutions, as it reflects the institution’s ability to absorb losses.

Income Statement

Interest Income and Expense: Financial institutions earn interest income from loans and investments and incur interest expense on deposits and borrowings. The net interest income (interest income minus interest expense) is a primary revenue source.

Non-Interest Income: Fees, trading revenue, and other non-interest income sources, such as wealth management fees, are significant for financial institutions.

Loan Loss Provision: The amount set aside to cover potential loan defaults. This expense affects net income and indicates the institution’s approach to risk management.

Analyzing Key Metrics for Financial Institutions

Interest Rate Spread and Sensitivity

Interest rate changes impact financial institutions significantly, as they affect net interest income. Understanding interest rate sensitivity and the spread between interest-earning assets and interest-bearing liabilities helps evaluate future income stability.

Interest Rate Spread: The difference between the average yield on earning assets and the average rate paid on interest-bearing liabilities.

Interest Rate Sensitivity: Measures how changes in interest rates affect net interest income. Institutions with high sensitivity may experience volatile earnings when rates fluctuate.

Loan Quality and Risk Management

Analyzing the quality of the loan portfolio is essential for assessing credit risk.

Loan Loss Reserves: Reflect the institution’s expectation of future loan losses. Adequate reserves are crucial for risk management, especially in economic downturns.

Charge-Off Rate: Measures the rate at which loans are written off due to non-payment, indicating the institution’s effectiveness in managing credit risk.

Fee-Based Income and Non-Interest Revenue

Fee-based income provides a stable revenue source, diversifying earnings away from interest income, which is subject to interest rate fluctuations.

Types of Non-Interest Income: Includes fees from wealth management, asset management, trading, and other services. High non-interest income as a percentage of total income indicates income diversification.

Impact on Profitability: Financial institutions with strong fee-based income are less vulnerable to changes in interest rates, contributing to stable profitability.

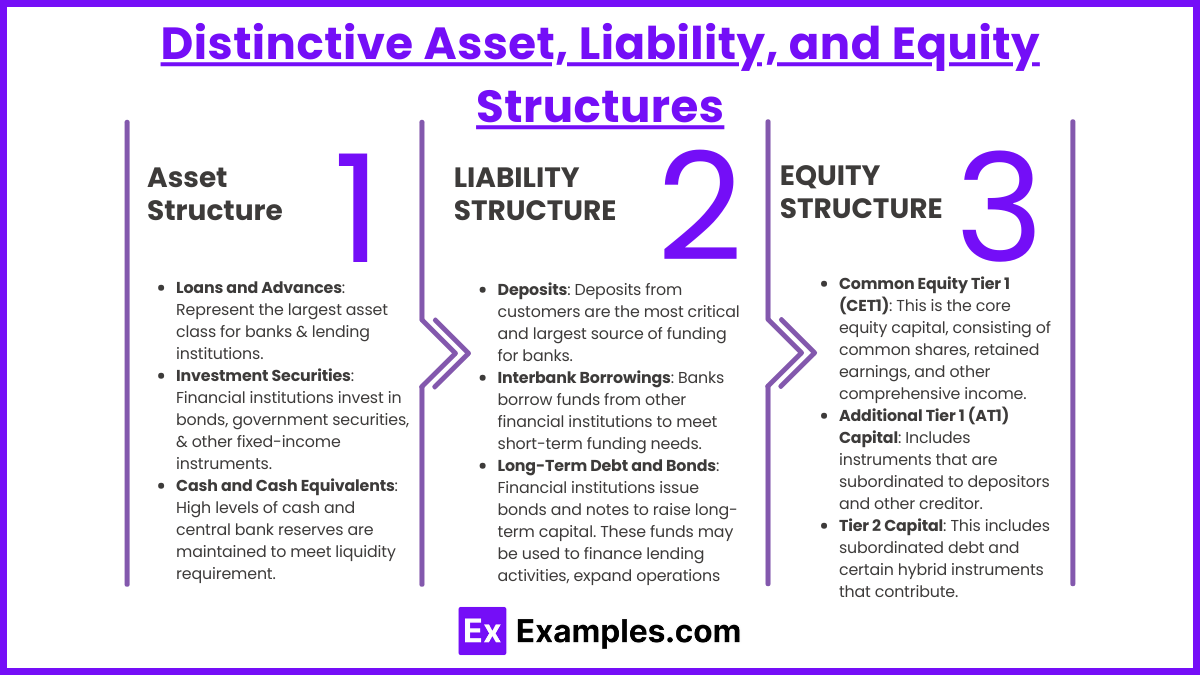

Distinctive Asset, Liability, and Equity Structures

Financial institutions, such as banks, insurance companies, and investment firms, have unique asset, liability, and equity structures compared to non-financial companies. These differences reflect their core business activities, which revolve around managing deposits, issuing loans, investing, and managing financial risks. Here’s an overview of the distinctive structures in each component:

1. Asset Structure

Financial institutions’ assets primarily consist of loans, investment securities, and cash. These assets are highly liquid and income-generating, given that interest income and investment returns are critical revenue sources.

Key Components of Assets

Loans and Advances: Represent the largest asset class for banks and lending institutions. These are income-generating assets that include personal loans, mortgages, business loans, and credit facilities. Loans are typically carried at amortized cost but may be subject to fair value adjustments based on credit quality.

Investment Securities: Financial institutions invest in bonds, government securities, and other fixed-income instruments. These provide interest income and are classified as held-to-maturity, available-for-sale, or trading securities. Each category has different accounting treatments based on regulatory guidelines.

Cash and Cash Equivalents: High levels of cash and central bank reserves are maintained to meet liquidity requirements and regulatory mandates. Financial institutions must hold enough cash to ensure stability during times of stress or customer withdrawal surges.

Interbank Assets: Deposits placed with other banks, loans to other financial institutions, or overnight lending contribute to interbank assets. These transactions are a significant source of liquidity and are commonly used for short-term funding needs.

Example: A bank’s asset portfolio might consist of 60% loans, 20% investment securities, 10% cash, and 10% interbank assets, reflecting a strong emphasis on income-generating assets.

2. Liability Structure

Liabilities for financial institutions are distinct because they often involve customer deposits, short-term and long-term borrowings, and derivatives. Unlike non-financial companies, which rely on debt or accounts payable, financial institutions leverage deposits as their primary source of funds.

Key Components of Liabilities

Deposits: Deposits from customers are the most critical and largest source of funding for banks. They include checking accounts, savings accounts, time deposits, and certificates of deposit (CDs). Deposits are typically classified as current liabilities since customers can withdraw funds on demand (for demand deposits).

Interbank Borrowings: Banks borrow funds from other financial institutions to meet short-term funding needs. These are usually overnight or short-term loans, often in the form of repurchase agreements (repos) or federal funds in the United States.

Long-Term Debt and Bonds: Financial institutions issue bonds and notes to raise long-term capital. These funds may be used to finance lending activities, expand operations, or meet regulatory capital requirements. Unlike deposits, long-term debt is usually less liquid and often carries interest rate obligations.

Derivatives and Hedging Instruments: Financial institutions engage in derivatives, such as interest rate swaps and currency forwards, to manage financial risk. These liabilities represent obligations that arise from derivative contracts, often classified as fair value liabilities or notional exposures.

Example: A bank’s liability structure may include 70% customer deposits, 10% interbank borrowings, 10% long-term debt, and 10% in derivatives and hedging instruments, showing a reliance on deposits for funding.

3. Equity Structure

The equity structure of financial institutions is designed to meet regulatory capital requirements and provide a buffer against losses. Equity is typically categorized into Tier 1 and Tier 2 capital under Basel regulatory frameworks, which assess the institution's capital adequacy.

Key Components of Equity

Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1): This is the core equity capital, consisting of common shares, retained earnings, and other comprehensive income. CET1 is the most important type of capital as it provides the primary buffer against losses.

Additional Tier 1 (AT1) Capital: Includes instruments that are subordinated to depositors and other creditors but are not common equity. AT1 often includes perpetual preferred shares that do not have a fixed maturity date, providing additional loss-absorbing capital.

Tier 2 Capital: This includes subordinated debt and certain hybrid instruments that contribute to the institution’s capital base. Tier 2 capital is used to absorb losses only after Tier 1 capital is depleted.

Reserves and Surplus: These include retained earnings, statutory reserves, and other surplus funds set aside from net income. Reserves enhance the institution’s financial stability and may be required to meet regulatory guidelines for risk coverage.

Example: A financial institution’s equity might consist of 60% CET1, 20% AT1, and 20% Tier 2 capital, reflecting a robust capital structure aimed at satisfying regulatory capital requirements and ensuring financial stability.

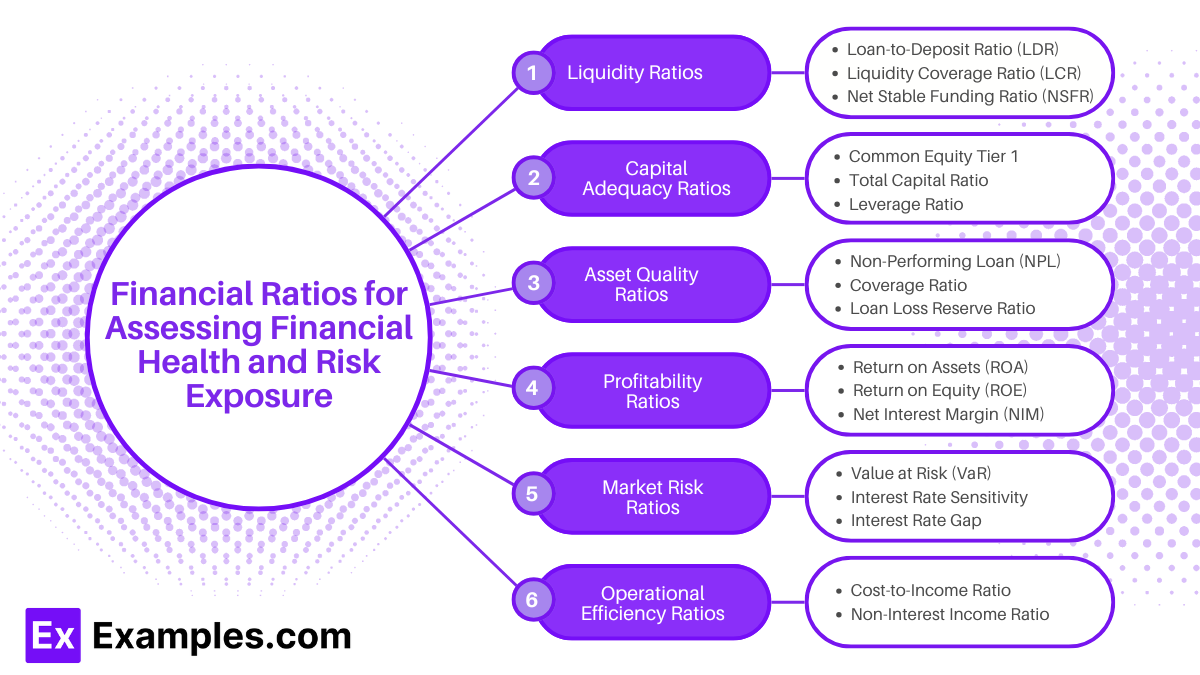

Financial Ratios for Assessing Financial Health and Risk Exposure

Financial ratios provide valuable insights into a financial institution’s overall health, efficiency, risk management, and ability to meet regulatory and operational goals. Below are some key financial ratios that help assess the financial strength and risk exposure of banks, insurance companies, and other financial institutions.

1. Liquidity Ratios

Liquidity ratios evaluate the institution’s ability to meet short-term obligations and manage cash flow. These ratios are especially critical for financial institutions, as liquidity ensures stability and trust.

Loan-to-Deposit Ratio (LDR): Reflects the balance between loans provided and customer deposits. A balanced ratio indicates a healthy loan portfolio and adequate funds to cover withdrawals.

Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR): Assesses if the institution has enough high-quality liquid assets to cover cash outflows during a stress period. A high ratio suggests strong liquidity.

Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR): Measures whether long-term assets are backed by stable funding sources. A solid NSFR means the institution is well-prepared to meet long-term obligations.

2. Capital Adequacy Ratios

Capital adequacy ratios determine the institution’s capacity to withstand financial losses. They are essential for regulatory compliance and resilience against economic downturns.

Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) Ratio: Evaluates the institution’s core capital against its risk-weighted assets. A high CET1 ratio signals strong loss-absorbing capacity.

Total Capital Ratio: Includes all qualifying capital in comparison to risk-weighted assets, indicating overall capital strength and regulatory compliance.

Leverage Ratio: Shows the proportion of core capital to total assets, providing a straightforward measure of capital adequacy without risk-weighting. A higher ratio indicates a stronger capital foundation.

3. Asset Quality Ratios

Asset quality ratios assess the health of a financial institution’s loan portfolio and exposure to credit risk, providing insight into potential loan losses.

Non-Performing Loan (NPL) Ratio: Examines the percentage of loans that are non-performing (in default). Lower ratios indicate healthier loan portfolios with minimal risk of default.

Provision Coverage Ratio: Reflects how well loan loss provisions cover non-performing loans. A high coverage ratio indicates the institution’s readiness to absorb potential loan losses.

Loan Loss Reserve Ratio: Shows the institution’s preparedness for future loan defaults by comparing loan loss reserves to total loans.

4. Profitability Ratios

Profitability ratios gauge the institution’s ability to generate income efficiently, balancing costs and income from core financial activities.

Return on Assets (ROA): Assesses how effectively the institution uses its assets to produce profit. Higher ROA indicates more efficient asset utilization.

Return on Equity (ROE): Measures profitability relative to shareholder equity, reflecting the institution’s ability to generate returns for investors.

Net Interest Margin (NIM): Highlights the profitability of lending activities by comparing interest income to interest expenses. A higher NIM suggests effective lending and borrowing practices.

5. Market Risk Ratios

Market risk ratios evaluate the institution’s exposure to changes in market conditions, such as interest rates and exchange rates, which can affect income and asset values.

Value at Risk (VaR): Estimates potential losses in investment portfolios due to market fluctuations over a set period and confidence level. Lower VaR indicates reduced exposure to market risk.

Interest Rate Sensitivity: Measures how changes in interest rates impact net interest income, providing insight into the institution’s earnings volatility.

Interest Rate Gap: Assesses the difference between rate-sensitive assets and liabilities, highlighting exposure to interest rate fluctuations.

6. Operational Efficiency Ratios

Operational efficiency ratios focus on how well the institution controls costs relative to revenue, highlighting operational effectiveness.

Cost-to-Income Ratio (Efficiency Ratio): Compares operating expenses to total income, with a lower ratio indicating better cost control and efficient operations.

Non-Interest Income Ratio: Examines the portion of income from non-interest sources, showing the institution’s income diversification.

Impact of Economic and Market Factors on Financial Institutions

Economic and market factors greatly influence the operations, profitability, and stability of financial institutions. Factors like interest rates, inflation, economic growth, and market volatility directly affect institutions' financial performance, risk exposure, and regulatory compliance. Here’s an overview of some key economic and market factors and their impacts on financial institutions.

1. Interest Rates

Interest rates are one of the most critical economic factors affecting financial institutions, particularly banks, which rely heavily on interest income.

Impact on Net Interest Margin (NIM): Changes in interest rates influence the spread between interest income from loans and interest expenses on deposits. Higher rates often increase NIM, improving profitability. Conversely, lower rates can compress NIM, impacting revenue.

Loan Demand: Lower interest rates typically boost loan demand, as borrowing costs decrease, encouraging individuals and businesses to take loans. Conversely, high interest rates can dampen loan demand.

Asset Values and Bond Portfolios: Interest rate increases can reduce the value of existing bond portfolios due to the inverse relationship between bond prices and yields, leading to potential unrealized losses.

Example: A central bank rate cut can lead to reduced interest income for banks, lowering profitability if the decrease in loan rates outpaces the decrease in deposit rates.

2. Economic Growth

The overall economic environment, including growth rates and business cycles, impacts financial institutions' asset quality, loan demand, and credit risk.

Loan Growth and Demand: Economic expansion typically leads to increased loan demand as businesses invest and consumers spend more. In contrast, during recessions, demand for loans may decline as businesses and consumers cut back on spending.

Credit Quality: During economic downturns, financial institutions face higher credit risk, as unemployment and reduced business earnings increase the likelihood of loan defaults.

Investment Returns: Economic growth positively impacts investment portfolios, with stocks and other growth-oriented assets often yielding better returns in expansionary phases.

Example: In a recession, banks may see higher default rates on loans and may adopt stricter lending criteria to manage credit risk.

3. Market Volatility

Market volatility, influenced by political events, economic news, or other shocks, affects trading income, asset valuations, and risk exposure for financial institutions.

Impact on Trading Revenues: Investment banks and other institutions with significant trading activities can benefit from increased trading volumes during volatile periods. However, heightened volatility also raises the risk of substantial trading losses.

Asset Valuation: Market volatility affects the value of assets held by financial institutions. For example, stock market declines can reduce the value of equity holdings, impacting balance sheets and potentially leading to write-downs.

Investor Confidence and Fund Flows: Volatile markets often decrease investor confidence, which may lead to outflows from mutual funds or other investment products managed by financial institutions.

Example: A geopolitical event that causes sudden stock market drops can lead to asset devaluation and increased risk exposure for institutions with large equity portfolios.

Examples

Example 1: Bank Performance Evaluation

Analyzing a bank’s performance involves reviewing various financial metrics, such as net interest margin, return on assets, and non-performing loans ratio. For instance, a financial analyst may assess how well a bank is managing its interest income versus interest expenses to determine profitability. This evaluation helps stakeholders understand the bank's operational efficiency and risk management practices.

Example 2: Credit Risk Assessment

Financial institutions must analyze credit risk to determine the likelihood of default by borrowers. Analysts evaluate borrowers' creditworthiness through financial ratios, credit scores, and historical payment behavior. For example, a mortgage lender might analyze a potential homebuyer’s income stability, credit history, and debt-to-income ratio to make informed lending decisions, which directly impacts the institution’s profitability and risk exposure.

Example 3: Regulatory Compliance Analysis

Financial institutions are subject to various regulations to ensure stability and protect consumers. Analysts assess compliance with regulations such as the Dodd-Frank Act or Basel III standards. For instance, a bank might undergo a compliance audit to verify it maintains adequate capital reserves and liquidity ratios. Understanding regulatory requirements is crucial for institutional stability and maintaining public trust.

Example 4: Investment Portfolio Analysis

Financial institutions, particularly investment banks and asset managers, conduct thorough analyses of their investment portfolios. This includes evaluating asset allocation, performance against benchmarks, and risk-adjusted returns. For example, an investment manager may assess the performance of equities versus fixed income to adjust the portfolio in line with market conditions and client objectives, ensuring that the institution meets its fiduciary responsibilities.

Example 5: Market Position and Competitive Analysis

Analyzing a financial institution's market position involves comparing its performance with peers and understanding its competitive advantages. This can include reviewing market share, pricing strategies, and customer satisfaction levels. For instance, a credit union might analyze its member services and fee structures against other local financial institutions to identify areas for improvement and enhance its market position, ultimately aiming to attract and retain customers.

Practice Questions

Question 1

Which of the following is a key performance indicator for assessing a bank's profitability?

A) Return on Equity (ROE)

B) Current Ratio

C) Debt-to-Equity Ratio

D) Operating Cash Flow

Correct Answer: A) Return on Equity (ROE).

Explanation: Return on Equity (ROE) is a crucial performance metric for banks and other financial institutions, as it measures how effectively a company is using its equity to generate profits. A higher ROE indicates better profitability and efficient use of shareholders’ funds. The current ratio assesses liquidity rather than profitability, the debt-to-equity ratio indicates leverage, and operating cash flow focuses on cash generation from operations, making them less relevant for evaluating profitability specifically.

Question 2

What is the primary purpose of conducting a credit risk assessment in financial institutions?

A) To determine the institution's overall profitability.

B) To evaluate the likelihood of borrower default.

C) To assess the institution's market share.

D) To analyze the institution's regulatory compliance.

Correct Answer: B) To evaluate the likelihood of borrower default.

Explanation: The primary purpose of a credit risk assessment is to determine the risk that a borrower will default on their loan obligations. Financial institutions use this assessment to evaluate a borrower's creditworthiness based on their financial history, credit score, and other relevant factors. Understanding credit risk helps institutions make informed lending decisions and manage potential losses. Options A, C, and D relate to different aspects of financial analysis but do not specifically address the goal of assessing credit risk.

Question 3

Which of the following best describes the role of regulatory compliance in financial institutions?

A) It focuses solely on maximizing profits.

B) It ensures adherence to laws and regulations that govern financial practices.

C) It involves predicting future market trends.

D) It is irrelevant to the overall risk management strategy.

Correct Answer: B) It ensures adherence to laws and regulations that govern financial practices.

Explanation: Regulatory compliance in financial institutions is essential to ensure that they operate within the legal framework established by governmental and regulatory bodies. Compliance helps protect consumers, maintain the integrity of the financial system, and prevent fraudulent activities. It plays a crucial role in risk management by reducing the likelihood of legal penalties and financial losses. Options A and C misrepresent the primary focus of compliance, while option D incorrectly suggests that compliance is unimportant to risk management strategies.