Preparing for the CFA Exam requires a comprehensive understanding of “Analysis of Long-Term Assets,” a core topic in financial reporting and analysis. Mastery of asset valuation methods, depreciation techniques, amortization, and impairment considerations is essential. This knowledge provides critical insights into assessing a company’s financial stability and asset management effectiveness, both of which are crucial for achieving a high CFA score.

Learning Objectives

In studying “Analysis of Long-Term Assets” for the CFA, you should learn to understand and apply various asset management and valuation methods, including historical cost, fair value, and revaluation models. Develop proficiency in calculating depreciation, amortization, and impairment effects on financial statements. Analyze and interpret the impact of long-term asset turnover ratios on profitability and capital efficiency. Evaluate asset management strategies to understand their effect on a company’s financial stability and growth potential. Additionally, gain the ability to apply long-term asset analysis in real-world scenarios, such as assessing investment strategies, resource allocation, and financial forecasting within an organization.

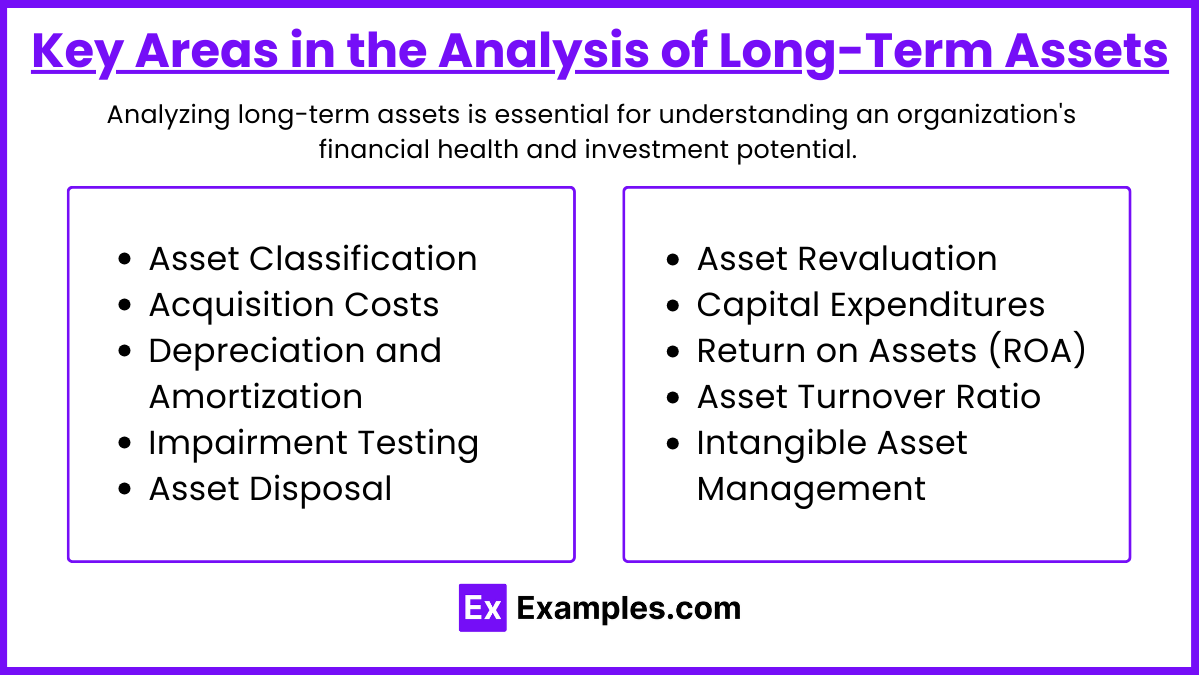

Key Areas in the Analysis of Long-Term Assets

Analyzing long-term assets is essential for understanding an organization’s financial health and investment potential. Here are key areas to consider:

- Asset Classification

Distinguishing between tangible (e.g., property, equipment) and intangible assets (e.g., patents, goodwill) helps in proper financial reporting and tax treatment. - Acquisition Costs

Includes all costs incurred to bring an asset to its intended use. This helps in determining the baseline value for depreciation or amortization. - Depreciation and Amortization

Systematic allocation of asset costs over their useful life, which affects net income and tax liabilities. Different methods (straight-line, declining balance) provide varied impacts on financial statements. - Impairment Testing

Regular testing ensures that assets are not overvalued on the balance sheet. Impairment losses occur when an asset’s market value falls below its carrying value. - Asset Disposal

Recording gains or losses upon disposal provides insight into the company’s asset management efficiency. Proper disposal practices also impact cash flows and earnings. - Asset Revaluation

Periodic revaluation, particularly for international firms, can reflect fair market value, aligning with IFRS standards and giving stakeholders a clearer financial picture. - Capital Expenditures (CapEx)

Tracking CapEx versus operating expenses is essential for assessing an organization’s growth investment, as it influences cash flow and debt levels. - Return on Assets (ROA)

Analyzing ROA helps in measuring asset efficiency and profitability. A high ROA indicates effective utilization of assets to generate earnings. - Asset Turnover Ratio

This ratio measures how efficiently a company uses its assets to generate sales. High turnover indicates efficient use of assets, while low turnover might signal over-investment or underutilization. - Intangible Asset Management

Proper valuation and protection of intangibles like intellectual property can significantly impact market valuation and competitive advantage.

Types of Analysis of Long-Term Assets

1. Investment Analysis

- Focuses on the viability, stability, and profitability of an investment.

- Evaluates assets to determine whether they align with the company’s strategic goals.

- Utilizes metrics like Net Present Value (NPV) and Internal Rate of Return (IRR).

2. Depreciation Analysis

- Reviews methods and rates of depreciation on assets.

- Determines the impact on financial statements and tax obligations.

- Common methods include Straight-Line, Double Declining Balance, and Units of Production.

3. Impairment Analysis

- Assesses whether an asset’s carrying value exceeds its recoverable amount.

- Identifies potential asset write-downs when the market value declines.

- Aimed at maintaining accurate asset valuation on the balance sheet.

4. Asset Utilization Analysis

- Analyzes how efficiently assets are being used in operations.

- Often includes asset turnover ratios and benchmarking.

- Highlights underutilized or idle assets for possible reallocation or disposal.

Applications Analysis of Long-Term Assets

Long-term assets, often known as non-current assets, are crucial for organizations because they represent investments that will provide value over multiple accounting periods. Here are some key applications of long-term assets:

1. Supporting Core Operations

- Fixed Assets: Machinery, equipment, and buildings are foundational for production and operational activities in manufacturing or service sectors.

- Real Estate: Properties owned by companies often appreciate in value and provide space for offices, retail locations, or storage.

2. Revenue Generation

- Patents and Trademarks: Intellectual property assets allow companies to generate revenue through licensing or by providing unique product offerings.

- Leasehold Improvements: Enhancements to leased property can attract tenants or improve business operations, increasing revenue potential.

3. Enhanced Financial Stability and Borrowing Power

- Collateral for Loans: Long-term assets can be used as collateral for securing loans, as their value often remains stable or appreciates over time.

- Balance Sheet Strength: High-value assets improve a company’s asset base, making it more attractive to investors and lenders.

4. Depreciation for Tax Efficiency

- Tax Deduction through Depreciation: Companies can claim depreciation on physical assets, which reduces taxable income and enhances cash flow.

- Amortization of Intangible Assets: Similar to depreciation, amortization on intangible assets spreads costs over time, benefiting financial statements.

5. Strategic Planning and Expansion

- Research and Development (R&D): Investments in R&D are considered long-term assets, especially when patents are filed, enabling new products and market expansion.

- Acquisitions and Mergers: Acquiring long-term assets, including intangibles like goodwill, can strengthen market position or provide new revenue streams.

Examples

Example 1. Assessing Capital Investment Decisions

When companies plan to acquire new long-term assets, such as machinery, buildings, or land, an in-depth analysis is essential to ensure these investments align with long-term strategic goals. By evaluating the expected cash flows, potential depreciation, and maintenance costs, companies can determine if the investment will generate sufficient returns over time. This analysis helps avoid overspending on assets that may not yield the anticipated benefits, ensuring capital is allocated to projects with optimal financial impact.

Example 2. Evaluating Depreciation and Asset Lifespan

Depreciation is a key component in the analysis of long-term assets, as it affects the value of assets over time and the company’s reported earnings. For example, using different depreciation methods (like straight-line or declining balance) can significantly alter the valuation and tax implications of long-term assets. This analysis enables a company to assess the remaining useful life of assets, forecast replacement needs, and plan for reinvestment, ensuring that asset-related expenses are accurately recorded and aligned with financial planning.

Example 3. Conducting Impairment Tests for Accurate Reporting

Long-term assets are susceptible to impairment when market conditions change, such as a drop in asset value due to obsolescence or economic shifts. Performing regular impairment tests helps a company ensure its balance sheet reflects an accurate value of long-term assets. For example, if a company finds that a manufacturing plant is underutilized or its equipment is outdated, an impairment analysis will adjust the book value to reflect fair market conditions. This process prevents overvaluation, improving financial transparency for stakeholders and investors.

Example 4. Planning for Capital Expenditures (CAPEX)

Long-term assets often require substantial capital expenditures for upgrades or replacement. Using an analysis of these assets helps businesses plan for future CAPEX by estimating the costs associated with maintaining or expanding asset capacity. For instance, a utility company might assess its energy-generating assets to determine when it will need to upgrade infrastructure to meet growing demand. This analysis supports budgeting and resource allocation, ensuring that the company can maintain operational efficiency without unexpected financial strain.

Example 5. Forecasting Asset Performance and Productivity

Companies rely on long-term assets to generate revenue, so it’s crucial to analyze asset performance periodically. This involves reviewing asset productivity and comparing it to industry benchmarks to ensure efficient utilization. For example, a transportation company may analyze the performance of its fleet to see if it meets desired efficiency levels or if upgrades are needed. Such insights inform strategic decisions, allowing the company to optimize asset performance and maximize the return on investment in long-term assets over time.

Practice Questions

Question 1

Which of the following is NOT a common purpose of analyzing long-term assets?

A) Planning for future capital expenditures

B) Estimating asset productivity and performance

C) Determining short-term cash flow needs

D) Conducting impairment tests to ensure accurate reporting

Answer: C) Determining short-term cash flow needs

Explanation: Analyzing long-term assets primarily focuses on long-term financial planning, assessing asset performance, and ensuring accurate asset valuation through impairment tests. Short-term cash flow needs, however, are typically associated with current assets and liquidity management rather than long-term assets. While long-term asset analysis can indirectly influence cash flow by affecting capital planning, its primary purpose is not to manage short-term cash requirements.

Question 2

What is depreciation in the context of long-term assets?

A) The process of allocating the cost of a long-term asset over its useful life

B) The sale of a long-term asset at a loss

C) An increase in the value of a long-term asset over time

D) A one-time expense associated with the purchase of a long-term asset

Answer: A) The process of allocating the cost of a long-term asset over its useful life

Explanation: Depreciation is an accounting method used to allocate the cost of a tangible long-term asset over its estimated useful life. This systematic expense reflects the asset’s decline in value as it is used, and it affects both the asset’s book value and the company’s financial statements. Options B, C, and D are incorrect as they describe different events: a sale at a loss (B), appreciation (C), or a one-time expense (D), none of which accurately define depreciation.

Question 3

Why is impairment testing important when analyzing long-term assets?

A) It helps ensure the asset’s market value increases over time.

B) It allows companies to keep assets recorded at their original purchase cost.

C) It adjusts the asset’s book value if the asset’s fair market value has significantly declined.

D) It is only relevant when a company decides to sell the asset.

Answer: C) It adjusts the asset’s book value if the asset’s fair market value has significantly declined.

Explanation: Impairment testing is critical for recognizing when a long-term asset’s fair market value has dropped below its book value due to changes in economic conditions, asset obsolescence, or other factors. By adjusting the book value to reflect current fair market conditions, impairment testing ensures that the company’s financial statements remain accurate. Options A, B, and D are incorrect: the purpose of impairment is not to ensure an increase in value, retain original cost, or limit application to asset sales, but rather to reflect fair market value in financial reporting.