Asset allocation involves the strategic distribution of an investor’s portfolio across various asset classes to achieve specific investment objectives while managing risk. In real-world scenarios, asset allocation decisions are influenced by a range of practical constraints such as liquidity requirements, tax considerations, regulatory restrictions, and individual risk tolerance. These constraints make the theoretical allocation strategies more complex and require a nuanced approach. Professionals must consider both qualitative and quantitative factors, including economic conditions, investor preferences, and time horizons, to design portfolios that align with practical limitations while still striving for optimal returns. Effective asset allocation with real-world constraints aims to balance risk and reward in a manner that aligns with an investor’s unique situation.

Learning Objectives

In studying “Asset Allocation with Real-World Constraints” for the CFA, you should learn to analyze the impact of practical constraints—such as liquidity, regulatory requirements, taxes, and transaction costs—on portfolio construction and asset allocation decisions. Understand how client-specific factors like risk tolerance, time horizon, and investment objectives influence asset allocation strategies. Evaluate different approaches to incorporate constraints in portfolio optimization, such as setting limits on asset classes or using optimization models that account for real-world restrictions. Assess the role of diversification and rebalancing within constrained portfolios to manage risk effectively. Additionally, develop the ability to apply asset allocation concepts under constraints in diverse investment scenarios, preparing you for practical challenges in portfolio management.

Understanding the Impact of Practical Constraints on Portfolio Construction

When constructing a portfolio, investors often face practical constraints that can limit their choices, influence asset allocation, and affect overall performance. These constraints—such as liquidity requirements, regulatory limitations, tax considerations, ethical preferences, and cost factors—require careful management to ensure the portfolio remains aligned with the investor’s goals. Here’s an exploration of how these constraints impact portfolio construction and the strategies used to address them.

1. Liquidity Requirements

Liquidity requirements refer to the need for quick access to cash without significantly affecting the portfolio’s value. Portfolios with high liquidity needs must prioritize liquid assets, which can limit potential returns but provide stability.

- Impact: Investors with liquidity needs may need to hold a higher proportion of cash and liquid assets, such as money market funds, Treasury bills, or highly traded stocks. This can limit exposure to higher-return assets like private equity or real estate, which are less liquid.

- Example: An investor who requires frequent withdrawals may allocate more to cash and short-term bonds to ensure funds are readily available, even if it means sacrificing some growth potential.

Strategy: To maintain liquidity, investors can create a tiered approach, holding different levels of liquidity based on withdrawal needs. For instance, short-term funds are kept in cash or money markets, while medium- and long-term investments can be allocated to less liquid, higher-yielding assets.

2. Regulatory and Legal Constraints

Many investors, especially institutional ones, must comply with regulatory and legal restrictions. These may limit the types of assets they can invest in, dictate minimum diversification standards, or cap exposure to certain sectors or asset classes.

- Impact: Regulatory constraints can limit investment choices, leading to a portfolio that may not fully align with optimal risk-return objectives. Certain sectors, such as high-risk or leveraged investments, may be off-limits, limiting potential returns.

- Example: Pension funds and insurance companies are typically restricted to conservative assets and must meet regulatory standards for diversification and risk management, which can limit exposure to high-growth assets.

Strategy: To comply with regulations while achieving investment goals, portfolio managers can use a diversified mix of permitted assets. For example, a pension fund might balance regulatory requirements by incorporating a range of high-quality bonds and blue-chip stocks to generate returns within permissible limits.

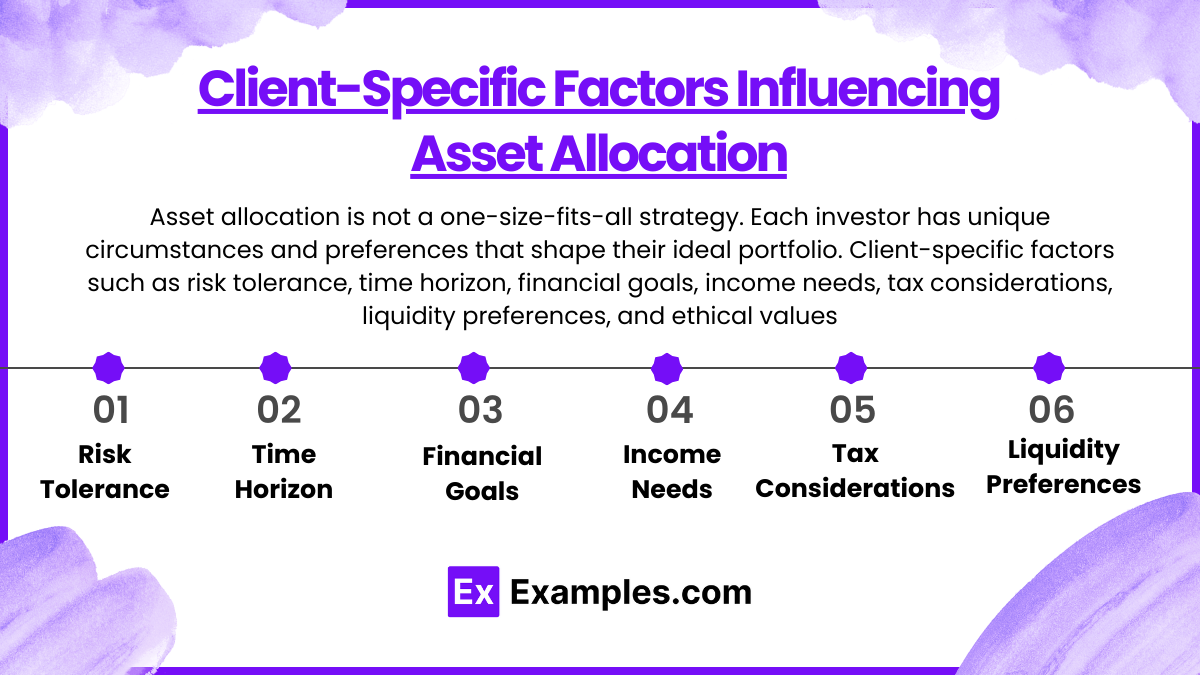

Client-Specific Factors Influencing Asset Allocation

Asset allocation is not a one-size-fits-all strategy. Each investor has unique circumstances and preferences that shape their ideal portfolio. Client-specific factors such as risk tolerance, time horizon, financial goals, income needs, tax considerations, liquidity preferences, and ethical values play a crucial role in designing a portfolio that aligns with the investor’s objectives. Here’s an in-depth look at how these factors influence asset allocation and guide investment decisions.

1. Risk Tolerance

Risk tolerance is an investor’s ability and willingness to endure volatility and potential losses. Understanding a client’s risk tolerance is essential to selecting an appropriate asset mix that balances growth potential with comfort during market fluctuations.

- Impact: A client with high risk tolerance may allocate a larger portion of their portfolio to equities or alternative investments with higher growth potential. In contrast, a risk-averse client may prefer bonds and other low-volatility assets to preserve capital and avoid large market swings.

- Example: A young investor with a high-risk tolerance might allocate 80% to stocks and 20% to bonds, while a retired client with low-risk tolerance might prefer a 30% stock, 70% bond allocation for stability.

Assessment: Risk tolerance can be assessed through questionnaires, past investment behavior, or discussions with the client, helping ensure that the portfolio aligns with their comfort level in both positive and negative market conditions.

2. Time Horizon

Time horizon refers to the period an investor plans to hold investments before needing to access their funds. Longer time horizons generally support higher risk, as there is more time to recover from market downturns.

- Impact: Clients with long-term goals (e.g., retirement in 30 years) can afford a more aggressive asset allocation, focusing on equities and growth-oriented assets. Shorter time horizons (e.g., saving for a home in 3 years) require safer, more liquid assets to protect capital and meet near-term needs.

- Example: A client saving for retirement in 20 years might have a high allocation to stocks (e.g., 70-80%) to capture growth, while a client with a 5-year goal may focus on bonds and cash to minimize risk.

Assessment: Discussing the client’s financial goals and timelines ensures that the portfolio’s asset allocation matches the required time horizon, providing growth for long-term objectives and stability for short-term needs.

3. Financial Goals

Financial goals vary widely among clients and may include wealth accumulation, income generation, capital preservation, or a specific target like education funding or buying property. The asset allocation strategy should reflect the unique purpose of the portfolio.

- Impact: Growth-focused goals often require a higher allocation to equities, while income or capital preservation goals favor bonds, real estate, or dividend-paying stocks. Clients with multiple goals may benefit from a diversified portfolio that balances these needs.

- Example: A client focused on wealth accumulation may allocate 80% to growth assets like stocks, while a retiree seeking income may prefer a 60% allocation to bonds, dividend stocks, or income-generating real estate.

Assessment: Establishing clear financial goals helps prioritize the right asset mix, enabling the portfolio to align with the client’s primary objectives, whether it’s building wealth, preserving capital, or generating income.

4. Income Needs

Clients who rely on their investments for income, such as retirees or those supplementing employment income, have specific needs that affect asset allocation. Portfolios that generate reliable income help meet day-to-day expenses and provide a sense of financial security.

- Impact: Income-focused clients often require stable, income-generating assets like bonds, dividend stocks, or real estate investments. High-growth but volatile assets, such as small-cap stocks, may be minimized to reduce income uncertainty.

- Example: A retiree needing regular income might allocate 40% to bonds, 30% to dividend-paying stocks, and 30% to real estate, ensuring a balanced mix of steady income sources.

Assessment: Evaluating income requirements allows for an allocation strategy that meets cash flow needs, ensuring the client’s expenses are covered without sacrificing portfolio stability.

5. Tax Considerations

Tax considerations significantly influence asset allocation, particularly for clients in high tax brackets. Effective tax planning within a portfolio can enhance after-tax returns and reduce unnecessary tax burdens.

- Impact: Clients may prefer tax-efficient investments like municipal bonds, ETFs, or tax-deferred accounts for assets that generate taxable income. Strategic asset location, where tax-inefficient assets are held in tax-advantaged accounts, can also optimize tax efficiency.

- Example: A high-income client may allocate municipal bonds in a taxable account for tax-free income and place high-turnover or income-generating assets (e.g., REITs, high-yield bonds) in a tax-deferred account like an IRA.

Assessment: Analyzing the client’s tax situation enables asset allocation that maximizes tax efficiency, balancing returns with tax liabilities and enhancing net income.

6. Liquidity Preferences

Liquidity preferences indicate a client’s need for easy access to funds. Some clients require liquid assets for emergencies or unexpected expenses, while others may be comfortable with illiquid investments if they offer higher returns.

- Impact: Clients with high liquidity needs may prioritize cash, money market funds, or highly liquid stocks, limiting exposure to illiquid assets like private equity or real estate. Those with lower liquidity needs may pursue illiquid investments for higher returns.

- Example: An investor with a high liquidity preference might allocate 30% to cash or short-term bonds, while a long-term investor with limited liquidity requirements may allocate more to real estate or other less liquid assets.

Assessment: Identifying liquidity needs ensures the portfolio’s assets are aligned with the client’s cash flow and withdrawal requirements, providing flexibility and security in case of unforeseen expenses.

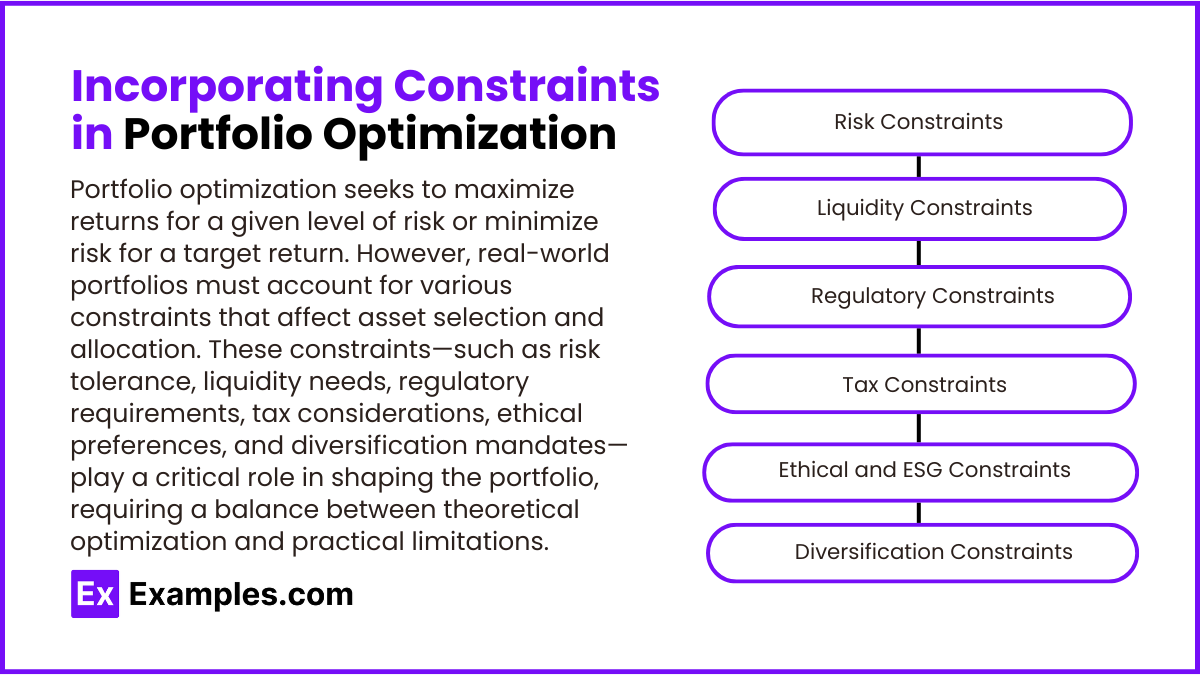

Incorporating Constraints in Portfolio Optimization

Portfolio optimization seeks to maximize returns for a given level of risk or minimize risk for a target return. However, real-world portfolios must account for various constraints that affect asset selection and allocation. These constraints—such as risk tolerance, liquidity needs, regulatory requirements, tax considerations, ethical preferences, and diversification mandates—play a critical role in shaping the portfolio, requiring a balance between theoretical optimization and practical limitations. Here’s an in-depth look at how to incorporate these constraints in portfolio optimization.

1. Risk Constraints

Risk constraints help ensure that the portfolio aligns with an investor’s tolerance for risk, covering limits on volatility, drawdowns, and exposure to specific assets or sectors.

- Application: Risk constraints can be applied by setting a maximum allowable level of portfolio volatility or by limiting the exposure to high-risk assets. Techniques like Value-at-Risk (VaR) and Conditional Value-at-Risk (CVaR) measure the potential loss in extreme scenarios, helping optimize portfolios within acceptable risk limits.

- Example: A portfolio may limit stock exposure to 60% to avoid excessive volatility, with additional constraints on sectors that are more volatile, like technology or emerging markets.

Implementation Strategy: Risk constraints are integrated by using risk models to monitor and adjust the portfolio’s risk exposure, ensuring that it remains within the investor’s comfort level.

2. Liquidity Constraints

Liquidity constraints address the need for accessible funds, especially in portfolios where investors may need to withdraw money frequently or with short notice.

- Application: To maintain liquidity, portfolios can impose constraints that limit the percentage of illiquid assets like private equity, real estate, or certain alternative investments. Liquidity constraints often specify a minimum percentage of the portfolio that must be held in cash or liquid assets.

- Example: A portfolio might require at least 20% allocation to liquid assets, such as cash, money market funds, or highly traded stocks, to ensure funds are available for immediate needs.

Implementation Strategy: Portfolios can use a “liquidity bucket” approach, allocating funds across highly liquid, moderately liquid, and illiquid assets according to withdrawal needs, enabling both short-term access and long-term growth.

3. Regulatory Constraints

Regulatory constraints are common for institutional investors, such as pension funds and mutual funds, that must comply with specific legal requirements regarding asset allocation, risk, and diversification.

- Application: Regulatory constraints may include limits on certain asset classes (e.g., speculative investments), minimum diversification standards, or limits on geographic exposure. These constraints ensure compliance and protect investors by maintaining a balanced risk profile.

- Example: Pension funds are often required to limit equity exposure to 70% and ensure that no single stock exceeds 5% of the total portfolio, enhancing diversification and reducing risk.

Implementation Strategy: Institutional portfolios often use compliance monitoring systems to ensure they adhere to regulatory constraints, adjusting allocations as needed to avoid breaches.

4. Tax Constraints

Tax considerations are crucial for optimizing after-tax returns, especially for high-net-worth individuals and taxable accounts. Tax constraints may include limits on turnover or asset allocation choices that reduce taxable events.

- Application: Portfolios can incorporate tax-efficient strategies, such as favoring tax-exempt or tax-deferred accounts, minimizing high-turnover investments, and implementing tax-loss harvesting to offset capital gains with losses.

- Example: A taxable portfolio might limit turnover by holding more index funds and ETFs, which are tax-efficient, while placing tax-inefficient assets like high-yield bonds or REITs in tax-deferred accounts.

Implementation Strategy: By structuring portfolios with tax-efficient funds and conducting periodic tax-loss harvesting, advisors can improve after-tax returns without altering the overall risk-return profile.

5. Ethical and ESG Constraints

Ethical and Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) constraints align the portfolio with an investor’s values by excluding certain sectors or emphasizing companies with positive social or environmental impacts.

- Application: Ethical constraints often restrict investments in sectors like tobacco, fossil fuels, or weapons manufacturing. ESG-focused portfolios may also prioritize companies with high ESG ratings, sustainable practices, and positive governance.

- Example: A socially responsible portfolio might exclude fossil fuel companies and overweight clean energy, healthcare, and technology, meeting both ethical standards and diversification needs.

Implementation Strategy: Advisors use ESG-screened ETFs or funds to construct portfolios that meet ethical guidelines, ensuring that investments align with both financial and personal goals.

6. Diversification Constraints

Diversification constraints prevent overconcentration in any single asset, sector, or geographic region, reducing risk by spreading exposure across multiple sources of returns.

- Application: Diversification constraints often limit the allocation to specific sectors, geographic regions, or asset classes. Minimum or maximum allocation constraints can enforce diversification and help avoid concentration risk.

- Example: A portfolio might limit individual stock holdings to a maximum of 5% each and require a minimum allocation of 10% to international equities, creating a balanced exposure across different markets.

Implementation Strategy: Using optimization models, diversification constraints are incorporated by setting bounds on allocations to different assets or asset classes, ensuring the portfolio maintains broad exposure.

Role of Diversification and Rebalancing in Constrained Portfolios

In constrained portfolios—where practical limits such as risk tolerance, liquidity needs, regulatory requirements, and ethical considerations affect asset allocation—diversification and rebalancing play essential roles. These two practices help manage risk, maintain alignment with investment objectives, and enhance potential returns, even within the bounds of constraints. Let’s explore how diversification and rebalancing contribute to optimizing constrained portfolios and why they are integral to effective portfolio management.

1. Role of Diversification in Constrained Portfolios

Diversification is the process of spreading investments across different asset classes, sectors, geographic regions, and investment styles to reduce risk and smooth out returns. In constrained portfolios, where asset choices may be limited, diversification helps manage these restrictions by enhancing portfolio resilience and balancing performance.

- Mitigating Risk: Diversification reduces the impact of poor performance in any single asset or asset class, which is particularly useful in constrained portfolios where risk limits are enforced. By holding a variety of investments, the portfolio is less vulnerable to the volatility of individual assets or sectors.

- Enhancing Stability: In portfolios with constraints like liquidity needs, ethical exclusions, or regulatory limits, diversification across allowable assets provides stability. It reduces reliance on a narrow range of assets, lowering the chance that external shocks will significantly disrupt portfolio performance.

- Maintaining Returns: Constrained portfolios may lack access to high-growth sectors due to ethical or regulatory limits, such as excluding fossil fuels or restricting speculative investments. Diversifying within allowed sectors or investment types—such as balancing equities across different industries or choosing multiple low-risk bonds—helps achieve growth potential despite these restrictions.

Example: In a portfolio restricted by ethical constraints (e.g., excluding fossil fuels), an investor could diversify by investing in technology, healthcare, and renewable energy stocks, spreading risk and capturing growth potential while maintaining alignment with ethical values.

2. Role of Rebalancing in Constrained Portfolios

Rebalancing is the periodic adjustment of a portfolio’s asset allocation to maintain target weights, ensuring it aligns with the investor’s goals and constraints. In constrained portfolios, rebalancing is crucial for controlling risk and keeping the portfolio consistent with constraints.

- Maintaining Risk Alignment: Over time, asset values fluctuate, causing the portfolio to drift from its target allocation. In constrained portfolios with specific risk limits, rebalancing prevents unintended risk exposure by restoring the original asset mix.

- Ensuring Compliance with Constraints: In portfolios with regulatory or ethical constraints, rebalancing helps ensure continued compliance. For instance, if a restricted sector becomes overrepresented due to market performance, rebalancing will bring it back within acceptable limits.

- Taking Advantage of Market Conditions: Rebalancing allows investors to capitalize on market performance by selling overperforming assets at high prices and buying underperforming ones at lower prices, which can enhance returns in the long term.

Example: Suppose a portfolio with a 60% stock and 40% bond allocation drifts to 70% stocks after a strong market rally. Rebalancing will bring stocks back to 60%, ensuring that the portfolio remains within its risk constraints and does not become overly equity-focused.

Examples

Example 1: Equity Financing in Startups

Many startups rely heavily on equity financing to fund their operations and growth. Founders often give up a percentage of ownership in exchange for capital from angel investors or venture capitalists. This approach allows them to raise funds without taking on debt, but it also dilutes ownership and control over the business.

Example 2: Debt Financing for Expansion

Established companies often use debt financing to fund expansion projects, such as acquiring new equipment or entering new markets. For example, a manufacturing firm may issue corporate bonds to raise capital, taking advantage of lower interest rates. This method allows the company to maintain ownership while benefiting from tax-deductible interest payments.

Example 3: Mixed Capital Structure in Corporations

A well-balanced capital structure typically includes both equity and debt. For instance, a large corporation might maintain a capital structure of 60% equity and 40% debt. This mix allows the company to leverage debt for growth while reducing the cost of capital and managing financial risk through the use of retained earnings and stock issuance.

Example 4: Impact of Capital Structure on Risk

The capital structure of a firm can influence its overall risk profile. For example, a company with a high proportion of debt relative to equity may experience higher financial risk during economic downturns, as it must meet interest obligations regardless of its revenue. Conversely, companies with lower debt levels may be more resilient to financial stress but may also experience slower growth.

Example 5: Use of Preferred Stock

Some companies incorporate preferred stock into their capital structure as a hybrid financing option. Preferred stockholders typically receive fixed dividends before common shareholders and have a higher claim on assets in the event of liquidation. For example, a utility company might issue preferred shares to raise capital while providing investors with relatively stable returns, balancing the needs of both equity and debt holders.

Practice Questions

Question 1

Which of the following techniques is commonly used to evaluate a company’s profitability?

A) Ratio analysis

B) Cost-volume-profit analysis

C) Trend analysis

D) All of the above

Correct Answer: D) All of the above.

Explanation: All of the listed techniques can be utilized to evaluate a company’s profitability. Ratio analysis helps assess profitability through metrics such as net profit margin and return on equity. Cost-volume-profit analysis examines how changes in costs and volume affect profit, while trend analysis looks at historical data to identify patterns over time. Using these techniques collectively provides a comprehensive view of a company’s profitability.

Question 2

What is the primary purpose of horizontal analysis in financial statements?

A) To compare a company’s financial performance with industry averages

B) To evaluate financial performance over multiple periods

C) To assess the financial health of a company at a specific point in time

D) To analyze the relationship between different financial metrics

Correct Answer: B) To evaluate financial performance over multiple periods.

Explanation: Horizontal analysis involves comparing financial statement line items over several periods to identify trends and growth patterns. This technique allows analysts to evaluate how specific accounts have changed over time, facilitating a better understanding of a company’s financial performance. Options A and D refer to other forms of analysis, while C describes vertical analysis.

Question 3

Which financial analysis technique focuses on the relationship between different financial statement items?

A) Ratio analysis

B) Vertical analysis

C) Horizontal analysis

D) Sensitivity analysis

Correct Answer: A) Ratio analysis.

Explanation: Ratio analysis is a financial analysis technique that examines the relationships between different financial statement items, such as profitability, liquidity, and solvency ratios. It allows analysts to assess a company’s financial health, operational efficiency, and performance compared to industry benchmarks. Vertical analysis focuses on the composition of financial statements, while horizontal analysis examines trends over time. Sensitivity analysis assesses how changes in one variable affect outcomes but does not primarily focus on the relationships between financial statement items.