Preparing for the CFA Exam demands a thorough understanding of fixed-income cash flows and types, an essential area within fixed-income investments. Mastery of bond structures, payment schedules, and various bond types equips candidates with the knowledge needed to analyze income streams and risk. This foundation is crucial for excelling on the CFA Exam.

Learning Objective

In studying “Fixed-Income Cash Flows and Types” for the CFA Exam, you should aim to understand the different types of fixed-income securities, such as government bonds, corporate bonds, and asset-backed securities, and their unique cash flow characteristics. Analyze how coupon payments, maturity structures, and amortization affect cash flow patterns and investor returns. Evaluate the principles behind interest rate structures and yield calculations, including fixed-rate and floating-rate bonds. Additionally, explore the impact of credit quality and issuer type on cash flow reliability and apply this knowledge to assess fixed-income instruments’ risk and return profiles in CFA practice scenarios.

What is Fixed-Income Securities?

Fixed-income securities are financial instruments that provide investors with regular, set interest payments, and return the principal at maturity. They are typically issued by governments, corporations, or other entities to raise capital, with the promise of a predictable income stream and repayment of the invested amount on a specific date. Common examples include bonds, treasury bills, and certificates of deposit. Fixed-income securities are generally considered lower-risk investments compared to equities, as they offer a stable income and are often less volatile.

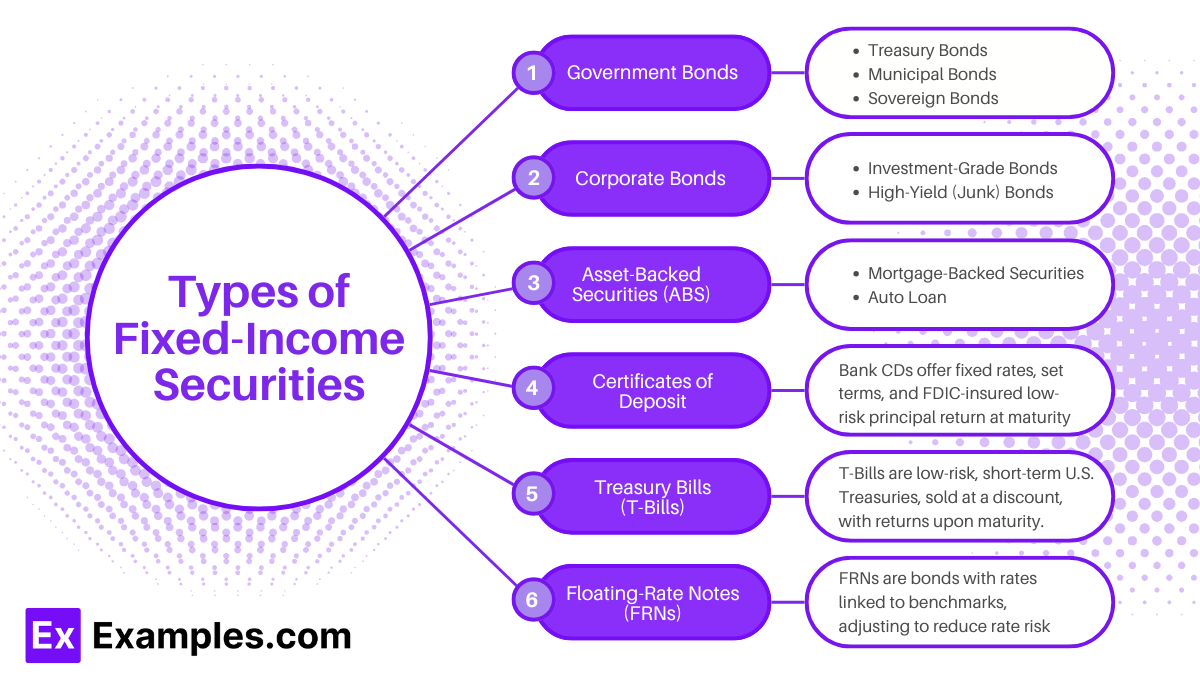

Types of Fixed-Income Securities

- Government Bonds

- Treasury Bonds: Issued by national governments, such as U.S. Treasury bonds, which are considered very low risk due to government backing. Treasury bonds typically have long-term maturities (10 years or more) and offer periodic fixed interest payments, making them a stable income source.

- Municipal Bonds: Issued by local governments, like states or cities, to finance public projects (e.g., schools, roads). Municipal bonds can offer tax advantages, as the interest income is often exempt from federal and sometimes state taxes.

- Sovereign Bonds: Similar to Treasury bonds but issued by foreign governments. Their risk level varies based on the issuing country’s economic stability, with developed countries generally offering lower-risk sovereign bonds than emerging markets.

- Corporate Bonds

- Issued by corporations to raise capital for various purposes, like expanding operations or financing new projects. Corporate bonds tend to offer higher yields than government bonds, as they come with added credit risk based on the issuer’s financial health. Corporate bonds are typically classified as:

- Investment-Grade Bonds: Issued by companies with strong credit ratings, meaning lower risk and relatively lower yields.

- High-Yield (Junk) Bonds: Issued by companies with lower credit ratings and thus higher credit risk, these bonds offer higher yields to compensate investors for the added risk.

- Issued by corporations to raise capital for various purposes, like expanding operations or financing new projects. Corporate bonds tend to offer higher yields than government bonds, as they come with added credit risk based on the issuer’s financial health. Corporate bonds are typically classified as:

- Asset-Backed Securities (ABS)

- Financial securities backed by a pool of assets, such as loans or receivables. These assets generate cash flows that are used to pay the ABS investors. Common examples include:

- Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS): Backed by a pool of home mortgages, where the mortgage payments form the cash flows for the security. MBS can be complex and sensitive to interest rates and prepayment risks.

- Auto Loan or Credit Card ABS: Backed by auto loans or credit card receivables, these securities provide cash flows from monthly loan or credit card payments made by consumers.

- Financial securities backed by a pool of assets, such as loans or receivables. These assets generate cash flows that are used to pay the ABS investors. Common examples include:

- Certificates of Deposit (CDs)

- Time deposits offered by banks, typically with fixed interest rates and fixed maturities ranging from a few months to several years. CDs pay a set interest rate over a specified period and return the principal at maturity. They are considered low-risk, as they are insured by government agencies like the FDIC in the U.S.

- Treasury Bills (T-Bills)

- Short-term government securities issued by the U.S. Treasury with maturities of one year or less. T-Bills are sold at a discount to their face value, and the difference between the purchase price and the face value is the investor’s return. They don’t pay periodic interest but are considered very low-risk, making them a safe place for investors to park cash in the short term.

- Floating-Rate Notes (FRNs)

- Bonds with variable interest rates, usually tied to a benchmark rate like LIBOR or the federal funds rate, and adjusted at regular intervals (e.g., quarterly). Because the interest payments adjust with prevailing rates, FRNs reduce interest rate risk for investors compared to fixed-rate bonds, making them appealing in rising rate environments

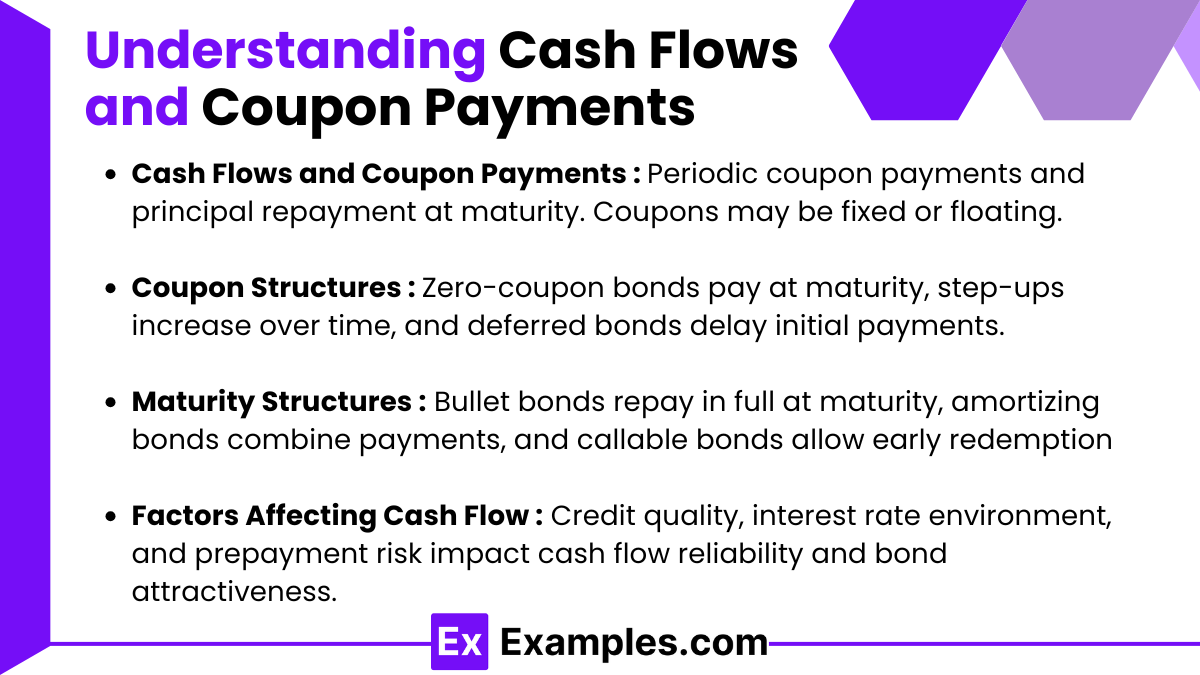

Understanding Cash Flows and Coupon Payments

Cash flows and coupon payments are core components of fixed-income securities, providing predictable income streams to investors. Here’s an overview of these elements and how they function:

- Cash Flows in Fixed-Income Securities

- Cash flows represent the periodic payments an investor receives from a bond or other fixed-income instrument. For most bonds, cash flows consist of regular coupon (interest) payments and a final principal repayment at maturity.

- Principal Repayment: At the bond’s maturity date, the issuer repays the bond’s face (par) value to the bondholder. This repayment is the last cash flow, completing the bond’s payment structure.

- Income Payments: In the case of bonds, the income is generally distributed as periodic coupon payments, though some fixed-income securities may have unique cash flow structures (e.g., amortizing securities like mortgage-backed securities where both principal and interest are paid over time).

- Coupon Payments

- Definition: Coupon payments are the interest payments made to bondholders, typically at regular intervals (e.g., semiannually, annually).

- Fixed-Rate Coupons: In fixed-rate bonds, the coupon rate is predetermined and does not change over the bond’s life. For example, a bond with a 5% annual coupon rate on a $1,000 face value would pay $50 in interest each year.

- Floating-Rate Coupons: Floating-rate bonds, or floaters, have coupon rates that adjust periodically based on an underlying benchmark, such as the LIBOR (London Interbank Offered Rate) or the federal funds rate. These adjustments make floating-rate bonds more responsive to interest rate changes and reduce interest rate risk.

- Types of Coupon Structures

- Zero-Coupon Bonds: These bonds do not make periodic coupon payments. Instead, they are sold at a discount to their face value and mature at par, with the difference between purchase price and face value representing the bondholder’s return. Zero-coupon bonds are sensitive to interest rate changes due to their lump-sum payment at maturity.

- Step-Up Bonds: These bonds have coupons that increase at predetermined intervals, providing a rising income stream. Step-up bonds may appeal to investors expecting inflation or rising interest rates.

- Deferred Coupon Bonds: These bonds do not pay coupons for an initial period but start making regular coupon payments after a specified deferral period, making them useful in certain structured financing scenarios.

- Maturity Structures and Impact on Cash Flow Patterns

- Bullet Maturity: The entire principal is repaid in one lump sum at maturity. Most corporate bonds follow this structure, with regular coupon payments during the life of the bond and full principal repayment at the end.

- Amortizing Securities: These securities, such as mortgage-backed securities, include both interest and principal in each periodic payment. This gradual repayment of principal impacts cash flow predictability and can reduce reinvestment risk for investors.

- Callable Bonds: These bonds give the issuer the right to redeem the bond before maturity, often after a specified date. If the issuer calls the bond, the investor will receive the remaining principal sooner, which may impact future cash flows.

- Factors Influencing Coupon Payments and Cash Flow Reliability

- Credit Quality: Higher credit risk can lead to increased default risk, impacting the predictability of cash flows. Investors in lower-rated bonds (e.g., high-yield bonds) may face uncertainty if the issuer’s financial position changes.

- Interest Rate Environment: Rising interest rates can make existing bonds with fixed coupons less attractive, potentially reducing their market value. For floating-rate bonds, changing rates directly affect coupon payments, creating variability in cash flows.

- Prepayment Risk: For certain fixed-income securities, like mortgage-backed securities, borrowers may pay off loans early, impacting cash flows to investors. In a declining interest rate environment, prepayment risk is higher as borrowers refinance at lower rates, affecting income streams for investors

Credit Quality and Issuer Risk

Credit quality and issuer risk are fundamental in assessing the safety and return potential of fixed-income investments. Here’s a closer look:

- Credit Quality and Credit Ratings

- Definition: Credit quality reflects the likelihood that a bond issuer will meet its debt obligations (coupon payments and principal repayment).

- Credit Rating Agencies: Credit rating agencies like Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s (S&P), and Fitch provide credit ratings that assess an issuer’s financial health. These ratings range from high-quality (investment-grade) to low-quality (speculative or junk) bonds.

- Investment-Grade vs. High-Yield Bonds:

- Investment-Grade Bonds: Rated BBB- or higher by S&P or Baa3 or higher by Moody’s, investment-grade bonds are considered relatively low-risk.

- High-Yield (Junk) Bonds: Rated below BBB- or Baa3, these bonds carry higher credit risk but offer higher yields to compensate investors for the added risk.

- Issuer Type and Associated Risks

- Government Bonds: Issued by national governments, these are typically considered low-risk, especially for stable economies. However, foreign government bonds may have added political or currency risks.

- Corporate Bonds: Issued by companies, these bonds have varying risk levels depending on the company’s financial strength. Corporations with weaker credit ratings have a higher chance of defaulting, increasing issuer risk.

- Municipal Bonds: Issued by local governments, municipal bonds carry some risk of default, but this is generally low. Some municipal bonds are tax-exempt, enhancing their appeal for certain investors.

- Asset-Backed Securities (ABS): Issued against a pool of assets like mortgages or loans, ABS rely on the performance of the underlying assets, and may face prepayment and credit risks if borrowers default or pay off their loans early.

- Impact of Credit Events

- Default Risk: The risk that an issuer will fail to make timely payments. Default risk is higher for lower-rated bonds, affecting the bond’s yield and pricing.

- Credit Downgrade: A downgrade in credit rating can lead to a decline in bond price as the perceived risk increases.

- Event Risk: Certain events, like mergers, acquisitions, or regulatory changes, can impact an issuer’s ability to meet debt obligations and, therefore, the bond’s risk profile.

Examples

Example 1: U.S. Treasury Bonds

U.S. Treasury bonds are long-term debt securities issued by the U.S. government with maturities typically ranging from 10 to 30 years. Treasury bonds pay fixed semiannual coupon payments and are considered very low risk due to government backing. An investor purchasing a $1,000 Treasury bond with a 3% annual coupon will receive $15 every six months, plus the principal amount at maturity. The fixed-income cash flows from these bonds provide stable returns with minimal credit risk.

Example 2: Corporate Bonds

Corporate bonds are debt securities issued by companies to fund various projects or operations. These bonds often offer higher yields than government bonds to compensate for higher credit risk. For example, a $1,000 corporate bond from a well-established company with a 5% annual coupon will pay $25 every six months. Corporate bonds may be rated investment-grade or high-yield (junk) depending on the company’s creditworthiness, and cash flows are influenced by credit events like upgrades or downgrades.

Example 3: Zero-Coupon Bonds

Zero-coupon bonds are issued at a discount to their face value and do not pay periodic interest (coupons). Instead, they mature at par value, and the difference between the purchase price and face value represents the investor’s return. For instance, a zero-coupon bond purchased for $900 will mature at $1,000 after a specified period, providing a return of $100. Zero-coupon bonds are highly sensitive to interest rate changes, as they provide all cash flows at maturity rather than over time.

Example 4: Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS)

Mortgage-backed securities are asset-backed securities where cash flows come from a pool of mortgage loans. Investors receive monthly payments that include both principal and interest, as homeowners make mortgage payments. For example, a MBS backed by home loans will pay investors based on borrowers’ monthly payments. These securities have unique cash flow structures due to prepayment risk, where borrowers may pay off their mortgages early, especially when interest rates decline.

Example 5: Floating-Rate Notes (FRNs)

Floating-rate notes are bonds with variable interest rates, typically adjusted periodically based on a benchmark rate like LIBOR or the federal funds rate. This structure makes FRNs less sensitive to interest rate changes. For instance, a $1,000 floating-rate note with a rate of LIBOR + 1% will reset its coupon according to the LIBOR rate at each adjustment date, resulting in varying coupon payments. This type of security is attractive during rising interest rate environments, as the income adjusts with market rates, providing protection against interest rate risk

Practice Questions

Question 1

Which of the following best describes a zero-coupon bond?

A. A bond that pays a fixed coupon rate every six months until maturity.

B. A bond that pays a variable interest rate based on a benchmark.

C. A bond that is sold at a discount and pays no periodic interest payments.

D. A bond that has an increasing coupon payment over time.

Answer: C. A bond that is sold at a discount and pays no periodic interest payments.

Explanation: A zero-coupon bond is issued at a discount to its face value and does not pay periodic interest (coupon payments). Instead, it pays the full face value at maturity, with the return being the difference between the purchase price and face value. This bond type is highly sensitive to interest rate changes due to its lump-sum payment structure.

Question 2

Which type of bond typically has its interest rate adjusted periodically based on a benchmark rate?

A. Fixed-rate bond

B. Zero-coupon bond

C. Treasury bond

D. Floating-rate note

Answer: D. Floating-rate note

Explanation: A floating-rate note (FRN) has an interest rate that resets periodically based on a benchmark rate, such as LIBOR or the federal funds rate. This adjustment makes FRNs less sensitive to interest rate fluctuations compared to fixed-rate bonds. Other bonds, like zero-coupon bonds and fixed-rate bonds, do not adjust their interest rates periodically.

Question 3

A mortgage-backed security (MBS) typically provides which type of cash flow to investors?

A. Fixed annual payments until maturity

B. Monthly payments consisting of both principal and interest

C. A lump-sum payment at maturity

D. Variable payments based solely on interest rates

Answer: B. Monthly payments consisting of both principal and interest

Explanation: Mortgage-backed securities (MBS) generate cash flows from a pool of mortgage loans, where borrowers make monthly payments that include both principal and interest. This unique structure exposes investors to prepayment risk, as borrowers may pay off loans early, impacting the expected cash flow pattern.