Multinational Operations encompass the complexities of managing financial performance and reporting for entities operating across multiple countries. This topic explores the impact of foreign currency transactions, translation methods, and exposure to currency fluctuations on financial statements. It covers the strategic approaches to managing currency risks, consolidating foreign operations, and adhering to various international accounting standards. Understanding these aspects is essential for analyzing and interpreting the financial performance of multinational firms, ensuring accurate reporting, and making informed investment decisions in a global context.

Learning Objectives

In studying “Multinational Operations” for the CFA, you should learn to understand the financial and operational implications of conducting business across multiple countries. Familiarize yourself with the differences between functional, local, and reporting currencies, and how to determine the appropriate currency for financial statements. Analyze foreign currency translation methods and their impact on financial statements, including the temporal and current rate methods. Evaluate the effects of exchange rate fluctuations on financial performance and multinational financial reporting. Understand translation adjustments and how they impact the consolidated financial statements of multinational corporations. Additionally, gain insights into managing foreign exchange risk and assessing how currency movements affect cash flows, equity, and financial ratios.

Understanding Financial and Operational Implications of Multinational Business

Multinational businesses operate in multiple countries, which brings both opportunities and complexities. These complexities involve navigating various financial, regulatory, and operational landscapes, affecting aspects like currency exchange, tax policies, operational efficiency, and cultural considerations. Understanding these implications is essential for multinational companies to optimize performance and manage risks.

1. Currency Exchange and Foreign Exchange Risk

Operating in multiple currencies introduces foreign exchange (FX) risks, as exchange rates fluctuate, affecting revenue, expenses, and asset values.

- Translation Risk: The risk that arises when consolidating financial statements from foreign subsidiaries into the parent company’s currency. Changes in exchange rates impact the reported values of foreign assets, liabilities, revenue, and expenses.

- Transaction Risk: Occurs when there are transactions across currencies, such as sales, purchases, or loan repayments. A change in exchange rates between the transaction and settlement dates can result in gains or losses.

- Economic Risk: The risk that exchange rate changes will impact the company’s market competitiveness in foreign countries. If the local currency strengthens, the company’s products may become more expensive compared to local competitors.

Example: A U.S. multinational company that generates revenue in euros and incurs costs in dollars could see its profitability affected by a weakening euro or a strengthening dollar.

2. Taxation and Transfer Pricing

Multinational businesses face diverse tax laws across jurisdictions, impacting profitability and operational decisions.

- Double Taxation: Income earned abroad may be taxed by both the host country and the home country, depending on international tax treaties and the company’s structure. To mitigate double taxation, companies often use tax credits or deferral strategies.

- Transfer Pricing: When subsidiaries transact with each other, they set prices for goods, services, or intellectual property. These intercompany prices, or transfer prices, affect taxable income in each country. Regulators closely monitor transfer pricing to ensure it reflects arm’s length transactions.

- Tax Compliance and Planning: Each country has unique tax rates, tax credits, and allowable deductions. Effective tax planning helps companies minimize tax burdens and optimize cash flow. Compliance with global tax laws is essential to avoid penalties and ensure operational continuity.

Example: A multinational with subsidiaries in high-tax and low-tax jurisdictions might use transfer pricing to allocate more income to lower-tax regions, reducing overall tax expenses.

3. Regulatory and Compliance Challenges

Operating internationally subjects companies to various regulations, including environmental, labor, data privacy, and financial reporting laws.

- Labor Laws and Employment Standards: Labor regulations vary by country, affecting wages, working hours, and employee rights. Multinationals must comply with local labor laws, which can impact staffing costs and HR policies.

- Environmental and Product Standards: Different countries have distinct environmental and product safety standards, impacting production processes and supply chains. Non-compliance can result in fines, recalls, or bans.

- Financial Reporting Standards: Multinationals may need to prepare financial statements in accordance with multiple accounting standards, such as IFRS and U.S. GAAP. Consolidating financial information across subsidiaries requires reconciling these differences.

Example: A multinational operating in Europe must comply with the GDPR for data privacy, which may require changes in data collection, storage, and processing practices.

4. Operational Efficiency and Supply Chain Complexity

Operating in multiple locations brings challenges in managing global supply chains, production, and distribution.

- Logistics and Distribution Costs: Expanding into new regions requires logistics planning to optimize shipping routes, warehousing, and local distribution networks, impacting costs and delivery times.

- Supply Chain Diversification: Multinationals often source materials from various countries to manage risks and reduce costs. However, relying on suppliers in multiple countries introduces risks related to tariffs, transportation, and political stability.

- Technology Integration: Operating efficiently across borders requires robust technology and communication systems to synchronize operations, track inventory, and manage suppliers. Implementing consistent technology platforms ensures data accuracy and streamlined processes.

Example: A multinational manufacturing company may diversify suppliers across Asia to reduce reliance on a single country. However, it must account for potential delays and additional tariffs that can affect supply chain costs and timelines.

5. Financing and Capital Structure Considerations

Multinationals face unique challenges in structuring their capital and managing liquidity across countries.

- Local Financing Options: In some cases, it may be beneficial to finance local operations with debt in the host country’s currency, as this can act as a natural hedge against currency fluctuations.

- Repatriation of Profits: Bringing profits back to the home country can be subject to withholding taxes and other regulatory restrictions. Companies must carefully manage cash flows to optimize liquidity while minimizing tax impacts.

- Capital Allocation and Investment Decisions: Multinationals may allocate capital to different subsidiaries based on local market opportunities, tax rates, and political stability. Deciding where to invest requires balancing potential returns with regulatory and currency risks.

Example: A U.S.-based multinational with a European subsidiary might finance that subsidiary with euro-denominated debt, minimizing FX risk and potentially reducing tax liabilities through interest deductions.

6. Cultural and Human Resource Challenges

Managing employees across countries involves adapting to diverse cultural norms, labor markets, and management practices.

- Cultural Differences: Each country has distinct cultural norms that impact management styles, employee motivation, and customer expectations. Multinationals must train leaders and adapt HR practices to suit local cultures while maintaining a consistent corporate culture.

- Talent Acquisition and Retention: Hiring skilled employees in foreign countries can be challenging due to competition, immigration laws, and language barriers. Retention strategies often require adapting benefits, compensation, and career development opportunities to local expectations.

- Remote and Multinational Team Management: Coordinating teams across time zones and cultures requires strong communication and collaboration tools. Multinationals may need to invest in training and development to foster effective cross-cultural teams.

Example: A U.S.-based multinational with operations in Japan might adapt its management practices to emphasize respect, hierarchy, and consensus-building, aligning with Japanese cultural expectations.

7. Strategic Planning and Market Entry Risks

Expanding into new markets brings both growth opportunities and strategic risks.

- Market Entry Strategy: Entering a new country requires choosing the appropriate entry strategy, such as a joint venture, acquisition, or greenfield investment. Each option has implications for control, risk, and regulatory compliance.

- Political and Economic Risks: Countries differ in terms of political stability, economic conditions, and policy unpredictability. Multinationals must assess these factors to mitigate risks that could impact revenue or asset security.

- Competitive Landscape: Competition varies across regions, with local firms often having an advantage in understanding customer preferences and regulatory environments. Adapting product offerings and marketing strategies is critical to compete effectively.

Example: A multinational entering a highly regulated market might choose a joint venture with a local firm to navigate regulatory challenges and leverage the partner’s market knowledge.

8. Financial Reporting and Performance Measurement

Multinationals need accurate reporting and measurement tools to assess the performance of subsidiaries and manage consolidated financial results.

- Performance Metrics: Setting financial and operational performance metrics across subsidiaries is complex, as economic conditions and currency fluctuations impact profitability. KPIs must be adapted to local conditions and currencies.

- Segment Reporting: Multinational companies often report by geographic or operational segments, allowing stakeholders to assess performance in each region. Segment reporting provides insights into profitability, revenue growth, and risks by market.

- Consolidation and Currency Translation: Consolidating financial results from various subsidiaries requires currency translation adjustments, impacting net income and equity. Multinationals use average exchange rates for the income statement and end-of-period rates for balance sheet items.

Example: A multinational with high growth in Asia and slower growth in Europe might use segment reporting to provide stakeholders with detailed insights into each region’s contributions.

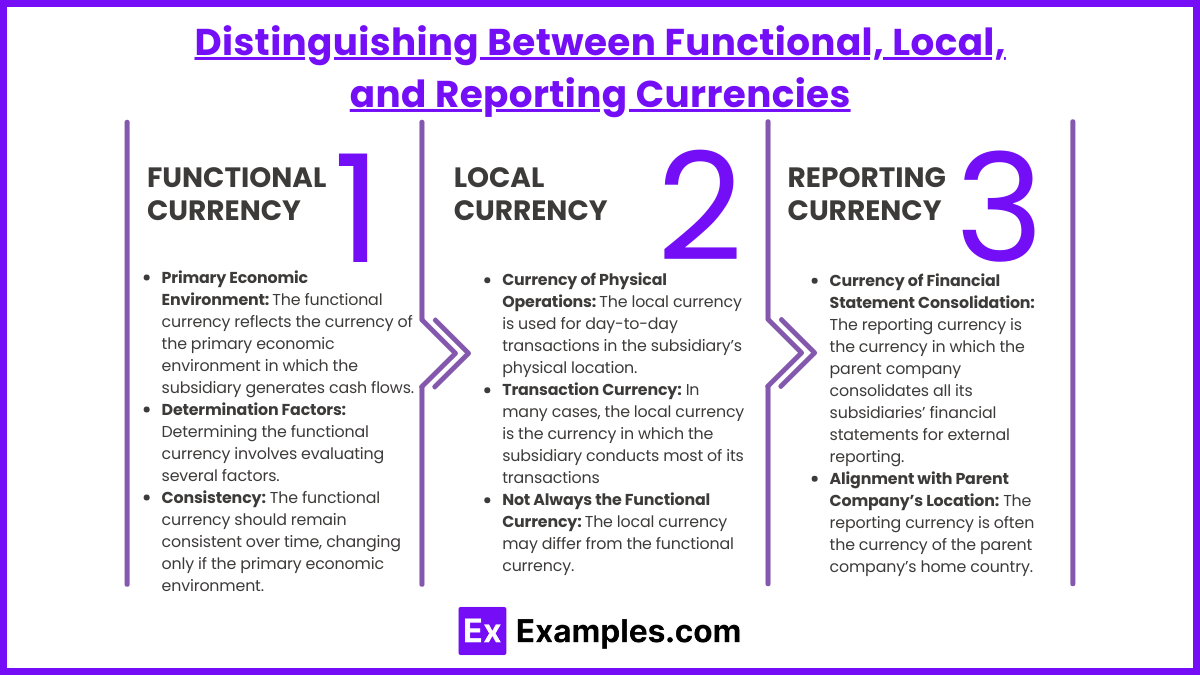

Distinguishing Between Functional, Local, and Reporting Currencies

In multinational financial management, currencies play a crucial role in accurately capturing and reporting business activities across countries. To address the complexities of operating in different economic environments, accounting standards define three types of currencies: functional currency, local currency, and reporting currency. Each type serves a specific purpose in financial transactions, measurement, and reporting, allowing multinational companies to consolidate and present financial results consistently and in compliance with regulatory standards.

1. Functional Currency

The functional currency is the primary currency of the economic environment in which a subsidiary or business unit operates. It is the currency in which the company conducts most of its transactions, generates revenue, incurs expenses, and influences pricing.

Characteristics of Functional Currency

- Primary Economic Environment: The functional currency reflects the currency of the primary economic environment in which the subsidiary generates cash flows.

- Determination Factors: Determining the functional currency involves evaluating several factors, including:

- Currency of Sales: The currency in which the company’s sales and revenues are predominantly denominated.

- Currency of Costs: The currency used for the majority of the company’s operating expenses, such as labor, materials, and rent.

- Financing Currency: The currency in which the company’s financing activities, such as loans, are conducted.

- Currency of Cash Flows: The currency in which cash flows are typically generated and retained by the business.

- Consistency: The functional currency should remain consistent over time, changing only if the primary economic environment of the subsidiary changes.

Example: A U.S.-based company has a subsidiary in Japan that generates revenue in Japanese yen, pays expenses in yen, and borrows funds in yen. For this subsidiary, the yen is likely the functional currency.

2. Local Currency

The local currency is the currency of the country where the business unit or subsidiary is physically located. It is the currency typically used for day-to-day transactions, employee salaries, and local expenses. However, the local currency does not always align with the functional currency, especially when the subsidiary operates in a different economic environment than its physical location.

Characteristics of Local Currency

- Currency of Physical Operations: The local currency is used for day-to-day transactions in the subsidiary’s physical location.

- Transaction Currency: In many cases, the local currency is the currency in which the subsidiary conducts most of its transactions, particularly with local suppliers and customers.

- Not Always the Functional Currency: The local currency may differ from the functional currency. For example, a subsidiary located in a country with a high inflation rate may use the U.S. dollar as its functional currency while using the local currency for everyday transactions.

Example: A Canadian-based subsidiary of a European company uses the Canadian dollar for everyday operations, local purchases, and payroll. Here, the Canadian dollar is the local currency, even if the functional currency may differ.

3. Reporting Currency

The reporting currency is the currency in which the multinational company prepares its consolidated financial statements. It is the currency in which the parent company reports its overall financial performance to shareholders, regulators, and other stakeholders.

Characteristics of Reporting Currency

- Currency of Financial Statement Consolidation: The reporting currency is the currency in which the parent company consolidates all its subsidiaries’ financial statements for external reporting.

- Alignment with Parent Company’s Location: The reporting currency is often the currency of the parent company’s home country. For instance, a U.S.-based parent company typically uses the U.S. dollar as its reporting currency.

- Translation of Foreign Subsidiaries’ Financials: Financial results of foreign subsidiaries are translated from their functional currencies into the reporting currency for consolidated financial reporting.

- Exchange Rate Impact: Changes in exchange rates affect the value of foreign subsidiaries’ assets, liabilities, revenue, and expenses when translated into the reporting currency.

Example: A U.S.-based company with subsidiaries worldwide reports its consolidated financial statements in U.S. dollars. Here, the U.S. dollar is the reporting currency, regardless of the functional or local currencies of its subsidiaries.

Analyzing Foreign Currency Translation Methods

Foreign currency translation is essential for multinational companies, as it allows them to consolidate financial statements from subsidiaries operating in different currencies. The primary translation methods are the current rate method and the temporal method. Each method has distinct principles and impacts on financial statements, reflecting exchange rate changes and financial results differently.

1. Current Rate Method

The current rate method is typically used when a foreign subsidiary’s functional currency is different from the parent company’s reporting currency. It applies to subsidiaries that operate in a largely independent economic environment. The current rate method translates most financial statement items at the exchange rate on the balance sheet date.

Translation Process in the Current Rate Method

- Assets and Liabilities: Translated at the current exchange rate as of the balance sheet date.

- Equity Accounts: Translated at historical exchange rates, except for retained earnings, which is derived from the income statement and dividend distributions.

- Revenue and Expenses: Translated at the average exchange rate for the period (or the rate on the transaction date for more precision).

Effect on Financial Statements

- Translation Adjustment: Gains or losses from translation are reported as cumulative translation adjustment (CTA) in other comprehensive income (OCI), impacting equity rather than net income.

- Reduced Volatility in Earnings: Since translation adjustments do not flow through the income statement, the method avoids large impacts on reported earnings due to exchange rate fluctuations.

Example: A U.S.-based parent company has a subsidiary in Japan with the Japanese yen as the functional currency. Using the current rate method, the company translates the subsidiary’s assets and liabilities at the current exchange rate, while income statement items are translated at the average rate. Any resulting translation adjustment is recorded in OCI.

2. Temporal Method

The temporal method is used when the functional currency of the foreign subsidiary is the same as the parent’s reporting currency or when the subsidiary operates in a highly inflationary economy. It aligns closely with the parent company’s economic environment, as if the subsidiary’s transactions had been conducted in the reporting currency.

Translation Process in the Temporal Method

- Monetary Assets and Liabilities: Translated at the current exchange rate as of the balance sheet date. These items include cash, receivables, and payables.

- Non-Monetary Assets and Liabilities: Translated at historical exchange rates. Non-monetary items include inventory, fixed assets, and intangible assets.

- Revenue and Expenses: Expenses related to non-monetary assets, such as depreciation and cost of goods sold, are translated at historical rates, while other income and expenses are translated at the average rate.

Effect on Financial Statements

- Foreign Exchange Gains and Losses: Gains and losses resulting from currency translation under the temporal method flow through the income statement, affecting net income. This can result in higher earnings volatility.

- Focus on Economic Reality: Since the temporal method reflects the actual cost basis of non-monetary items, it provides an economic view of the subsidiary’s financials as though the transactions occurred in the parent’s currency.

Example: A U.S.-based company operates a subsidiary in a highly inflationary economy where the U.S. dollar is designated as the functional currency. Using the temporal method, monetary items are translated at the current rate, while inventory and fixed assets are translated at historical rates. Gains or losses from translation are recognized in net income.

3. Highly Inflationary Economies

In economies with high inflation, where the inflation rate is typically over 100% over a three-year period, the temporal method is required regardless of the subsidiary’s functional currency. This approach helps to stabilize financial reporting by mitigating the distortions caused by high inflation on non-monetary items.

Translation Adjustments in High-Inflation Economies

- Monetary Items: Translated at the current exchange rate, aligning with the latest inflationary effects.

- Non-Monetary Items: Recorded at historical rates to maintain accurate cost representation, minimizing inflation’s impact on balance sheet values.

- Impact on Net Income: Translation gains or losses flow through the income statement, capturing the effects of inflation on monetary items.

Example: A U.S.-based company with a subsidiary in a high-inflation country (e.g., Venezuela) would use the temporal method, treating the U.S. dollar as the functional currency. This approach helps avoid exaggerating asset values due to inflation and provides a more stable view of net income.

Evaluating the Effects of Exchange Rate Fluctuations on Financial Performance and Reporting

1. Translation Risk and Financial Reporting

Translation risk arises when a company consolidates the financial statements of foreign subsidiaries into its reporting currency. Exchange rate changes can impact the reported values of assets, liabilities, revenue, and expenses, even if the cash flows are unchanged in the local currency.

Effects on Financial Statements

- Balance Sheet: Assets and liabilities of foreign subsidiaries are translated at the current exchange rate as of the balance sheet date. When exchange rates fluctuate, the translated values change, leading to cumulative translation adjustments recorded in other comprehensive income (OCI).

- Income Statement: Revenue and expenses are usually translated at the average exchange rate over the reporting period. Exchange rate volatility during the period can lead to fluctuations in reported income, impacting profitability.

- Equity Impact: Translation gains or losses accumulate in the equity section as cumulative translation adjustment (CTA), affecting shareholders’ equity. These do not impact net income directly but can affect the overall financial position.

Example: A U.S.-based company with a European subsidiary records revenue in euros. If the euro weakens against the dollar, the translated revenue in U.S. dollars will decrease, impacting consolidated revenue and profitability, even though the subsidiary’s actual performance in euros may remain unchanged.

2. Transaction Risk and Operational Performance

Transaction risk arises from foreign currency transactions—such as sales, purchases, and loans—where payment is settled in a currency different from the functional currency. Exchange rate changes between the transaction date and the settlement date can result in transaction gains or losses, impacting net income.

Effects on Profitability

- Revenue and Expenses: Revenue from sales in foreign currencies and expenses paid in foreign currencies fluctuate with exchange rates, directly affecting gross profit margins and operating income.

- Foreign Currency Denominated Liabilities: Loans or payables in foreign currencies are revalued at each reporting date, creating potential gains or losses that impact net income.

- Operating Costs and Margins: Currency fluctuations can make costs more or less expensive relative to the revenue generated, affecting operating margins and overall profitability.

Example: A Canadian company sells goods in the United States with payments in U.S. dollars. If the Canadian dollar strengthens, the company receives less revenue when converted to Canadian dollars, reducing profit margins.

3. Economic Risk and Competitive Positioning

Economic risk (or operating exposure) reflects the long-term impact of currency changes on a company’s future cash flows and competitive position. Unlike transaction or translation risks, economic risk affects the company’s strategic planning, pricing, and market competitiveness over the long term.

Impact on Strategic Decisions

- Competitive Advantage: Exchange rate changes can affect a company’s relative pricing in foreign markets. A stronger home currency can make exports more expensive, reducing competitiveness abroad.

- Cost of Production: When production costs are denominated in a foreign currency, a favorable exchange rate can reduce costs and increase profitability. However, adverse currency changes increase costs, affecting the bottom line.

- Investment and Expansion Decisions: Multinationals often consider currency stability and economic risk when deciding where to invest or expand. Favorable currency conditions can enhance the attractiveness of foreign markets, while unstable currencies can increase risk.

Example: A Japanese electronics manufacturer exporting to the U.S. benefits when the yen weakens against the dollar, as products become cheaper for U.S. consumers, increasing demand. Conversely, a stronger yen reduces competitiveness and revenue.

Examples

Example 1: Global Supply Chain Management

Many multinational corporations operate extensive supply chains that span multiple countries. For example, a company like Apple designs its products in the United States but sources components from various countries, such as semiconductors from Taiwan and assembly from China. This global supply chain allows companies to minimize costs, optimize resources, and respond effectively to market demands.

Example 2: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)

A multinational company may invest directly in foreign operations by establishing production facilities or acquiring existing businesses in another country. For instance, Volkswagen has manufacturing plants in several countries, including Mexico and China, to serve local markets and reduce transportation costs. This type of investment enhances market presence and supports local economies.

Example 3: Cross-Border Marketing Strategies

Multinational companies often tailor their marketing strategies to fit the cultural and economic contexts of the countries in which they operate. For instance, McDonald’s adapts its menu offerings to local tastes, such as serving the McAloo Tikki burger in India. This localization of marketing efforts helps mulhttps://www.examples.com/cfa/multinational-operationstinational companies build brand loyalty and connect with diverse consumer bases.

Example 4: Cultural Adaptation in Human Resources

Multinational operations require companies to navigate various cultural and legal environments in their human resource practices. For example, a multinational corporation like Unilever may implement different labor practices and employee benefits to comply with local regulations and cultural norms in countries like the Netherlands and India. Understanding and adapting to these differences is essential for effective talent management across borders.

Example 5: Research and Development (R&D) Collaboration

Multinational companies often engage in collaborative R&D efforts across different countries to leverage global talent and innovation. For instance, pharmaceutical companies like Pfizer may have research teams in the United States, Germany, and China working together to develop new drugs. This collaboration can accelerate innovation and lead to more effective solutions by integrating diverse expertise and perspectives from different markets.

Practice Questions

Question 1

Which of the following is considered a post-employment benefit?

A) Stock options

B) Pension plans

C) Annual bonuses

D) Performance incentives

Correct Answer: B) Pension plans.

Explanation: Pension plans are a type of post-employment benefit designed to provide income to employees after they retire. They are typically funded during the employee’s working years and paid out after retirement. In contrast, stock options, annual bonuses, and performance incentives are forms of compensation that are typically awarded during an employee’s tenure, not after employment has ended.

Question 2

What is the main purpose of share-based compensation for employees?

A) To enhance short-term liquidity for the company

B) To align employee interests with those of shareholders

C) To minimize payroll taxes

D) To provide guaranteed income regardless of performance

Correct Answer: B) To align employee interests with those of shareholders.

Explanation: Share-based compensation, such as stock options or restricted stock units, is designed to align the interests of employees with those of the shareholders. When employees hold equity in the company, they are incentivized to work towards increasing the company’s value, as this will directly impact their own financial benefit. Options A, C, and D do not accurately describe the primary purpose of share-based compensation.

Question 3

Which of the following statements is true regarding the accounting for share-based payments?

A) Share-based payments are recorded as expenses only when the employee exercises their options.

B) The fair value of share-based payments is determined at the grant date.

C) Only stock options are subject to accounting standards for share-based payments.

D) Share-based payments have no impact on a company’s income statement.

Correct Answer: B) The fair value of share-based payments is determined at the grant date.

Explanation: According to accounting standards, the fair value of share-based payments is calculated at the grant date and recognized as an expense over the vesting period. This approach ensures that the costs associated with providing share-based compensation are appropriately matched with the performance benefits derived from the employees’ services. Option A is incorrect because expenses are recorded during the vesting period, not just at exercise. Option C is misleading, as all forms of share-based payments, not just stock options, are subject to accounting standards. Option D is also incorrect because share-based payments do affect the income statement as they are recognized as expenses.