Asset allocation is a critical process in investment management, involving the strategic distribution of an investor's capital among different asset classes such as equities, bonds, real estate, and cash. The primary objective of asset allocation is to balance risk and return according to the investor's financial goals, time horizon, and risk tolerance. By diversifying across asset classes, investors can potentially reduce the overall volatility of their portfolios, enhance returns, and mitigate risks. Asset allocation decisions are influenced by various factors including market conditions, economic outlook, and investor preferences. Understanding the principles and techniques of asset allocation is essential for constructing portfolios that align with both short-term and long-term objectives in the context of changing financial markets.

Learning Objectives

In studying "Overview of Asset Allocation" for the CFA, you should learn to understand the principles of asset allocation, including the role it plays in portfolio management and risk-return optimization. Develop the ability to distinguish between strategic and tactical asset allocation and how they align with different investment objectives and time horizons. Analyze the impact of diversification across asset classes, such as equities, fixed income, and alternatives, to reduce portfolio risk. Evaluate how market conditions, investor risk tolerance, and financial goals influence asset allocation decisions. Additionally, understand the significance of rebalancing and its effect on maintaining target allocations over time to achieve long-term investment objectives.

Principles of Asset Allocation in Portfolio Management

Asset allocation is the process of distributing investments across different asset classes—such as stocks, bonds, real estate, and cash—to achieve a balance between risk and return. It is a core principle of portfolio management, helping investors achieve their financial goals while managing the risks associated with market fluctuations. Effective asset allocation considers factors like an investor’s risk tolerance, time horizon, financial objectives, and market conditions. Here are the key principles of asset allocation in portfolio management.

1. Diversification

Diversification is a foundational principle of asset allocation that involves spreading investments across different asset classes and sectors to reduce risk.

Risk Reduction: By holding a mix of assets, diversification reduces the impact of a poor-performing asset on the overall portfolio.

Non-Correlated Assets: Diversifying among non-correlated or low-correlated assets (e.g., stocks and bonds) helps to balance performance since these assets often react differently to economic conditions.

Example: A portfolio with a mix of stocks, bonds, and real estate may perform more consistently, as losses in one area may be offset by gains in another.

2. Risk Tolerance Assessment

Risk tolerance is the investor’s ability and willingness to endure market volatility. Asset allocation should align with the investor's risk profile.

Aggressive vs. Conservative Allocations: Aggressive investors may prefer higher allocations to stocks for growth potential, while conservative investors might allocate more to bonds for stability.

Understanding Market Volatility: Investors with high risk tolerance may accept short-term volatility for potential long-term gains, whereas those with low risk tolerance may prioritize preserving capital.

Example: A young investor with a high-risk tolerance might have a portfolio with 80% in stocks and 20% in bonds, while a retiree may prefer 40% in stocks and 60% in bonds for stability.

3. Time Horizon Consideration

The time horizon is the expected period over which an investor will hold the portfolio before needing to withdraw funds. Longer time horizons allow for more risk-taking, while shorter ones require a more conservative approach.

Long-Term Goals: For long-term goals (e.g., retirement in 30 years), a higher allocation to equities is common, as investors can weather short-term market downturns.

Short-Term Goals: For short-term goals (e.g., buying a home in 3 years), a conservative allocation with a focus on liquid, stable assets like bonds or cash equivalents is preferable.

Example: A portfolio for a young investor focused on retirement may have a large equity allocation, while a portfolio for someone nearing retirement might shift towards bonds to reduce volatility.

4. Expected Return and Risk Trade-Off

Each asset class has different risk and return characteristics, with higher potential returns usually associated with higher risk. Balancing these elements is essential to align with the investor's goals.

Equity for Growth: Stocks typically offer higher potential returns but come with greater risk and volatility, suitable for investors seeking growth.

Fixed Income for Stability: Bonds provide more predictable returns and are generally less volatile than stocks, making them appropriate for income-focused or risk-averse investors.

Alternative Assets for Diversification: Real estate, commodities, or alternative investments can offer additional diversification and unique risk-return profiles, enhancing the portfolio's resilience.

Example: An investor seeking higher returns may allocate more to stocks, understanding that this comes with increased risk. A balanced portfolio might use bonds to offset stock volatility.

5. Rebalancing the Portfolio

Rebalancing is the process of realigning the portfolio’s asset allocation to maintain the desired level of risk over time, especially as market conditions change.

Periodic Rebalancing: Over time, asset values fluctuate, leading to allocation drift. Rebalancing involves selling overperforming assets and buying underperforming ones to restore the target allocation.

Automatic vs. Manual Rebalancing: Rebalancing can be done periodically (e.g., annually) or when asset classes deviate from target allocations by a certain threshold.

Example: If a portfolio with a target of 60% stocks and 40% bonds shifts to 70% stocks due to market gains, rebalancing would involve selling some stocks and buying bonds to return to the original allocation.

6. Aligning with Investment Objectives

Asset allocation should reflect the investor's financial goals, whether they’re focused on growth, income, or capital preservation.

Growth-Oriented Portfolios: For investors seeking capital appreciation, a higher allocation to equities and growth assets is typically recommended.

Income-Oriented Portfolios: For those needing regular income, higher allocations to dividend-paying stocks, bonds, and real estate investments may be more suitable.

Capital Preservation: For conservative investors, asset allocation may focus on bonds and cash to safeguard capital.

Example: A retiree needing income might have an asset allocation weighted towards income-generating assets like bonds and dividend-paying stocks rather than high-growth equities.

7. Tax Considerations

Different asset classes are subject to varying tax treatments, and these should be factored into asset allocation, especially for taxable accounts.

Tax-Advantaged Accounts: Place tax-inefficient investments (e.g., bonds, high-dividend stocks) in tax-advantaged accounts, such as IRAs, to defer taxes on gains.

Tax-Efficient Investments in Taxable Accounts: Allocate tax-efficient investments (e.g., municipal bonds, index funds) to taxable accounts to minimize annual tax liabilities.

Example: A high-income investor may allocate municipal bonds to taxable accounts since interest from municipal bonds is often tax-free, while high-turnover investments like actively managed funds are placed in tax-deferred accounts.

8. Economic and Market Environment Analysis

The economic and market environment, including factors like interest rates, inflation, and economic growth, can impact asset allocation strategies.

Interest Rate Environment: In a low-interest-rate environment, investors may allocate more to equities for returns. Conversely, rising rates might encourage shifts toward bonds.

Inflation Impact: High inflation erodes purchasing power, making real assets like real estate or commodities attractive as inflation hedges.

Market Cycles: Economic cycles (e.g., expansion, contraction) influence asset classes differently, and understanding the cycle can guide tactical shifts.

Example: In an inflationary environment, an investor might increase exposure to commodities and reduce bond allocations, as bonds tend to underperform during periods of high inflation.

Strategic vs. Tactical Asset Allocation

In portfolio management, asset allocation is the process of distributing investments across various asset classes to optimize returns while managing risk. Two primary approaches to asset allocation are Strategic Asset Allocation and Tactical Asset Allocation. While both aim to achieve a balanced and resilient portfolio, they differ in their methodology, frequency of adjustments, and response to market conditions. Here’s a breakdown of the differences, benefits, and applications of each approach.

1. Strategic Asset Allocation

Strategic Asset Allocation is a long-term, goal-oriented approach where a fixed asset mix is established based on an investor’s financial goals, risk tolerance, and time horizon. The allocation is typically rebalanced periodically (e.g., annually) to maintain the target proportions among asset classes.

Core Principles: Strategic allocation is based on the principle that each asset class has distinct characteristics and risk-return profiles. By setting and maintaining an optimal asset mix, this approach leverages the long-term historical performance and volatility of different asset classes.

Frequency of Adjustments: Adjustments are rare and generally occur only when rebalancing is needed due to market fluctuations. The portfolio is reset to the target allocation, keeping the mix aligned with the original plan, irrespective of short-term market movements.

Rebalancing Process: Rebalancing ensures that the portfolio remains aligned with the investor’s original risk profile. For example, if stock values rise significantly, the stock allocation may exceed its target percentage, necessitating rebalancing by selling stocks and reallocating to bonds or other assets.

Market Conditions: Strategic allocation does not respond to short-term market events or trends, relying on the idea that long-term market trends and historical averages will achieve the desired results over time.

Example: An investor with a moderate risk tolerance and a 20-year time horizon may set a strategic allocation of 60% stocks, 30% bonds, and 10% cash. This mix is based on the assumption that stocks will offer growth, bonds will provide income, and cash will offer stability. The portfolio is rebalanced annually to maintain these proportions.

2. Tactical Asset Allocation

Tactical Asset Allocation is a more flexible, short-term approach where the portfolio's asset mix is adjusted actively in response to current market conditions, economic trends, or expected market opportunities. It aims to capture short-term gains by taking advantage of perceived market inefficiencies or trends.

Core Principles: Tactical allocation is based on the belief that certain asset classes will outperform others in specific economic or market conditions. By temporarily adjusting the allocation, investors can potentially enhance returns or reduce risk during particular periods.

Frequency of Adjustments: Tactical allocation requires more frequent monitoring and adjustments based on market analysis and forecasts. Changes are often short-term, with the portfolio reverting to its strategic allocation when market conditions normalize.

Market Timing: Tactical allocation involves an element of market timing, as the investor seeks to capitalize on market trends or anticipated events (e.g., changes in interest rates, economic cycles). This approach requires careful analysis and expertise to avoid misjudging market trends.

Risk Management: While tactical allocation can potentially increase returns, it also introduces additional risk, as short-term adjustments may not always produce the expected results. This approach relies heavily on accurate market forecasts and timing.

Example: An investor with a strategic allocation of 60% stocks and 40% bonds may temporarily shift to 70% stocks and 30% bonds if they anticipate a strong bull market in equities. Once the market normalizes, they would return to the original 60/40 allocation.

The Impact of Diversification Across Asset Classes

Diversification is a fundamental principle of portfolio management that involves spreading investments across various asset classes to reduce overall risk. By combining different asset classes—such as stocks, bonds, real estate, and commodities—investors can create a balanced portfolio that is better equipped to withstand market volatility and achieve consistent returns. Here’s a closer look at the impact of diversification across asset classes, its benefits, and practical examples.

1. Risk Reduction

Diversification helps to reduce risk by spreading investments across assets that are not perfectly correlated. Different asset classes tend to perform differently under various economic conditions, so losses in one asset class may be offset by gains in another.

Correlation and Risk Management: Assets with low or negative correlations respond differently to the same economic events, which can smooth out portfolio performance over time. For example, stocks and bonds often have an inverse relationship, where bonds perform well during economic downturns, offsetting losses in equities.

Example: In a portfolio consisting solely of stocks, a market downturn could lead to significant losses. By diversifying with bonds, the investor might reduce losses because bonds may perform better or remain stable when stocks decline.

2. Enhanced Return Potential

Diversification allows investors to tap into the return potential of various asset classes, each of which may perform well under different circumstances. By including asset classes with strong growth potential, such as stocks, alongside stable assets like bonds, investors can optimize returns while managing risk.

Growth vs. Stability: Equities generally offer higher potential returns but come with higher volatility, while bonds provide stable, lower returns. By combining both, a diversified portfolio captures growth opportunities while maintaining some stability.

Example: A portfolio with 60% stocks and 40% bonds may achieve a higher return than a portfolio with only bonds, as equities historically yield higher returns over the long term, balancing stability with growth potential.

3. Reduced Portfolio Volatility

Diversification lowers portfolio volatility, helping investors avoid extreme fluctuations in portfolio value. This stability is especially important for risk-averse investors and those with shorter investment horizons.

Smoothing Out Market Ups and Downs: By combining assets that respond differently to market conditions, diversification smooths the overall returns. This consistency is valuable in maintaining confidence and helping investors stay committed to their long-term strategy.

Example: Adding real estate and commodities, which have unique performance patterns, to a traditional stocks-and-bonds portfolio can provide additional balance, reducing the overall portfolio’s volatility.

4. Protection Against Economic Cycles

Different asset classes are impacted in distinct ways by economic cycles, such as growth, recession, and inflationary periods. Diversification across asset classes helps portfolios endure these cycles by ensuring exposure to assets that may benefit during various phases.

Economic Resilience: While equities may struggle during a recession, bonds and commodities might perform better. Conversely, during economic growth, equities may outperform bonds, as companies generate higher earnings and attract more investment.

Example: Commodities like gold tend to perform well in inflationary periods, providing a hedge in a diversified portfolio that may suffer from inflation’s negative impact on bonds and certain stocks.

5. Improved Risk-Adjusted Returns

Diversification optimizes risk-adjusted returns, meaning investors can achieve a better return for the level of risk they’re taking. A well-diversified portfolio can offer higher returns without proportionally higher risk, as compared to a single-asset portfolio.

Sharpe Ratio Improvement: Diversification can increase the portfolio’s Sharpe ratio, which measures the return per unit of risk. A higher Sharpe ratio indicates a more efficient portfolio with better risk-adjusted returns.

Example: A portfolio diversified with stocks, bonds, and real estate might have a higher Sharpe ratio than a stock-only portfolio, as it reduces total portfolio volatility while maintaining competitive returns.

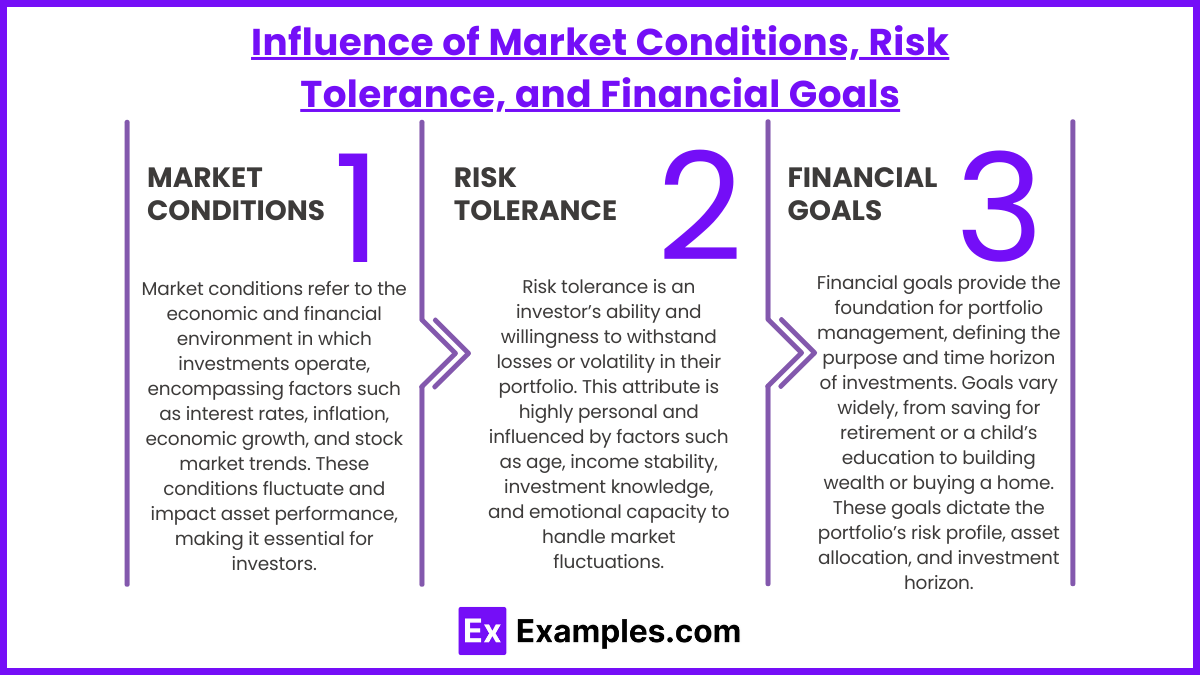

Influence of Market Conditions, Risk Tolerance, and Financial Goals

Portfolio management requires balancing various factors to meet the unique needs of each investor. Three key influences—market conditions, risk tolerance, and financial goals—shape the structure and strategy of a portfolio. Understanding these elements helps investors make informed decisions, adjusting allocations and risk management strategies to optimize performance in alignment with their personal and financial circumstances.

1. Market Conditions

Market conditions refer to the economic and financial environment in which investments operate, encompassing factors such as interest rates, inflation, economic growth, and stock market trends. These conditions fluctuate and impact asset performance, making it essential for investors to adjust their portfolios in response to changing market landscapes.

Economic Cycles: Different asset classes perform better in specific phases of the economic cycle (e.g., expansion, peak, contraction, trough). Understanding these cycles can guide portfolio adjustments.

Example: During economic expansion, equities may perform well, so investors might increase stock allocations. Conversely, in a recession, bonds or defensive sectors are typically favored for their stability.

Interest Rates: The central bank’s interest rate policies influence bond yields, borrowing costs, and overall market sentiment.

Example: In a low-interest-rate environment, equities and real estate might become more attractive due to lower yields on bonds. As rates rise, investors might shift toward fixed income for stable income.

Inflation: Rising inflation can erode purchasing power, impacting returns on investments, particularly cash and fixed income.

Example: To hedge against inflation, investors may allocate more to real assets like commodities and real estate, as these tend to retain or increase value in inflationary periods.

Geopolitical Events: Global events, such as trade tensions, wars, or political instability, can create market volatility and influence asset prices.

Example: In times of geopolitical tension, safe-haven assets like gold and U.S. Treasury bonds may become more attractive due to their relative stability.

Adapting to Market Conditions: Active portfolio managers often adjust allocations tactically in response to market conditions, while strategic managers might stay the course with their long-term allocations, relying on diversification to manage market risks.

2. Risk Tolerance

Risk tolerance is an investor’s ability and willingness to withstand losses or volatility in their portfolio. This attribute is highly personal and influenced by factors such as age, income stability, investment knowledge, and emotional capacity to handle market fluctuations.

Conservative Risk Tolerance: Conservative investors prioritize capital preservation and are less comfortable with volatility. They prefer stable, lower-risk investments like bonds, cash, and dividend-paying stocks.

Example: A conservative investor may hold a portfolio with 70% in bonds and 30% in stocks to ensure stability and generate predictable income.

Moderate Risk Tolerance: Moderate investors are comfortable with some volatility for potentially higher returns. They may allocate more to equities while keeping a portion in bonds for balance.

Example: A moderate investor might hold a 60/40 stock-to-bond portfolio, allowing for growth while providing a buffer against market downturns.

Aggressive Risk Tolerance: Aggressive investors are willing to accept high volatility for the chance of greater returns, often focusing on equities, growth stocks, or alternative investments.

Example: An aggressive investor with a long time horizon might allocate 90% to stocks and 10% to other assets, aiming for maximum capital appreciation.

Adjusting for Risk Tolerance: Portfolio construction should align with an investor’s risk tolerance to prevent emotional reactions to market downturns. A portfolio that reflects an investor’s comfort level with risk enables them to remain committed to their strategy even in volatile markets.

3. Financial Goals

Financial goals provide the foundation for portfolio management, defining the purpose and time horizon of investments. Goals vary widely, from saving for retirement or a child’s education to building wealth or buying a home. These goals dictate the portfolio’s risk profile, asset allocation, and investment horizon.

Short-Term Goals (1-3 Years): For goals within a short time frame, such as saving for a home, investors typically prioritize capital preservation and liquidity, favoring low-volatility assets like cash, money market funds, or short-term bonds.

Example: A portfolio for a short-term goal may be 80% cash and 20% short-term bonds, focusing on stability and quick access to funds.

Medium-Term Goals (3-10 Years): Medium-term goals, such as saving for college, require a balanced approach, with growth potential but controlled risk.

Example: For a medium-term goal, a 50/50 mix of stocks and bonds provides growth potential with a moderate level of risk, aiming to protect capital over the investment period.

Long-Term Goals (10+ Years): For long-term goals like retirement, investors can accept more volatility, as they have time to recover from short-term losses. Long-term portfolios are typically more growth-oriented, with higher allocations to equities.

Example: A retirement portfolio for a young investor might have 80% in stocks, 15% in bonds, and 5% in alternative investments, taking advantage of the growth potential over time.

Aligning with Financial Goals: Regularly reviewing financial goals helps investors adjust portfolios as goals evolve. For example, a portfolio initially set up for a young investor’s retirement may shift to include more bonds and cash as they approach retirement age, emphasizing capital preservation.

Examples

Example 1: Strategic Asset Allocation

This long-term investment strategy involves setting target percentages for various asset classes, such as stocks, bonds, and cash, based on an investor's risk tolerance, financial goals, and time horizon. For instance, a conservative investor might allocate 60% of their portfolio to bonds and 40% to equities to minimize risk, while a more aggressive investor might choose a higher allocation to stocks for potential growth.

Example 2: Tactical Asset Allocation

Unlike strategic asset allocation, tactical asset allocation allows investors to adjust their asset mix in response to short-term market conditions or economic trends. For example, if an investor anticipates a downturn in the stock market, they may temporarily increase their allocation to bonds or cash. This flexible approach seeks to capitalize on market opportunities while maintaining an overall investment strategy.

Example 3: Dynamic Asset Allocation

This approach involves continuously adjusting the asset mix based on market performance and changes in the investor's risk profile. For instance, if an investor's risk tolerance decreases due to nearing retirement, they may shift their portfolio from equities to a higher proportion of fixed-income securities. Dynamic asset allocation allows for a responsive strategy that adapts to both market conditions and personal circumstances.

Example 4: Core-Satellite Asset Allocation

In this strategy, investors maintain a core portion of their portfolio in low-cost, passive investments (like index funds) that provide market exposure while using satellite investments for active management and higher potential returns. For example, an investor might allocate 70% of their portfolio to a broad market index fund (core) and the remaining 30% to actively managed funds focused on specific sectors (satellites). This approach aims to balance risk and return.

Example 5: Risk-Based Asset Allocation

This method focuses on the risk associated with different asset classes rather than traditional classifications. For instance, an investor might analyze the volatility and correlation of various investments to construct a portfolio that maximizes returns for a given level of risk. By assessing historical performance and potential future risks, investors can make informed decisions about how to allocate their assets effectively. This approach can be particularly useful in volatile markets or uncertain economic conditions.

Practice Questions

Question 1

What is the primary objective of asset allocation in investment management?

A) To select individual securities for a portfolio

B) To minimize transaction costs

C) To balance risk and return by diversifying investments across asset classes

D) To time the market effectively

Correct Answer: C) To balance risk and return by diversifying investments across asset classes.

Explanation: The primary objective of asset allocation is to create a diversified investment portfolio that balances risk and return. By spreading investments across various asset classes, such as stocks, bonds, and real estate, investors can mitigate potential losses and enhance overall portfolio performance. Options A and D focus on specific investment strategies rather than the broader objective of asset allocation, while option B relates to cost management rather than investment strategy.

Question 2

Which of the following factors is most important when determining an investor's asset allocation strategy?

A) The investor's current income level

B) The investor's risk tolerance and investment goals

C) The performance of the stock market

D) The investor's age alone

Correct Answer: B) The investor's risk tolerance and investment goals.

Explanation: An investor's risk tolerance and investment goals are critical in shaping their asset allocation strategy. Understanding how much risk an investor is willing to take and what they aim to achieve (such as capital preservation, income generation, or long-term growth) will guide the appropriate distribution of assets. While income level and age can influence decisions, they do not encompass the full scope of factors relevant to a comprehensive asset allocation strategy.

Question 3

What is tactical asset allocation?

A) A long-term strategy that maintains a fixed asset mix

B) An approach that adjusts asset allocation based on market conditions

C) A method that focuses solely on high-risk investments

D) A strategy that avoids all types of market timing

Correct Answer: B) An approach that adjusts asset allocation based on market conditions.

Explanation: Tactical asset allocation is an investment strategy that allows investors to adjust their asset mix in response to short-term market conditions and economic trends. By temporarily shifting allocations among asset classes, investors aim to capitalize on perceived market opportunities and mitigate risks. In contrast, option A describes strategic asset allocation, while options C and D do not accurately represent the concept of tactical asset allocation.