Portfolio management for institutional investors involves tailoring investment strategies to meet the unique objectives and constraints of large organizations like pension funds, endowments, insurance companies, and sovereign wealth funds. These institutions manage substantial assets and must balance return objectives, risk tolerance, and regulatory requirements. Effective portfolio management includes strategic and tactical asset allocation, liability-driven investing, and risk management techniques to safeguard assets while meeting future obligations. Additionally, institutions increasingly incorporate ESG considerations, aligning investments with broader ethical and sustainability goals to fulfill fiduciary responsibilities.

Learning Objectives

In studying “Portfolio Management for Institutional Investors” for the CFA Exam, you should learn to understand the unique objectives, constraints, and regulatory considerations of various institutional investors, such as pension funds, endowments, foundations, insurance companies, and sovereign wealth funds. Analyze how these investors structure their portfolios through asset allocation strategies, including liability-driven investment (LDI), strategic asset allocation (SAA), and alternative investments. Evaluate key risk management techniques, such as duration matching, scenario analysis, and VaR, that align investments with institutional goals. Additionally, explore governance and ethical considerations in portfolio oversight, and apply your understanding to interpret institutional investor case studies in CFA practice scenarios.

1. Understanding Institutional Investors

Institutional investors include entities like pension funds, endowments, foundations, sovereign wealth funds, and insurance companies. Each type has unique objectives, constraints, and regulatory requirements. Institutional investors typically have large portfolios and unique governance structures, often including a board of trustees or an investment committee.

Types of Institutional Investors

- Pension Funds: These aim to provide retirement benefits. They can be defined-benefit (DB) or defined-contribution (DC) plans, each with differing risk profiles. DB plans, in particular, focus on ensuring the portfolio’s ability to meet future liabilities.

- Endowments and Foundations: These are established to fund specific activities, such as educational institutions or charitable causes. Their primary goal is maintaining purchasing power while generating a steady income to meet operational needs.

- Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs): Government-owned funds, often established to manage a country’s surplus reserves or specific financial resources. SWFs may target financial returns, economic stabilization, or intergenerational wealth transfer.

- Insurance Companies: These focus on meeting future liabilities arising from insurance claims. They are divided into life and non-life (or property and casualty) insurers, each with different liability structures, durations, and regulatory constraints.

2. Investment Objectives and Constraints

Investment Objectives and Constraints are the core elements of an investment policy statement (IPS), guiding an investor’s strategy. Each institution’s objectives depend on its purpose, risk tolerance, and liabilities:

- Return Objectives: Typically depend on the need to meet liabilities, preserve capital, and, in some cases, maximize returns. Foundations and endowments, for instance, aim to maintain purchasing power and thus require returns that outpace inflation.

- Risk Tolerance: Institutions have varying risk tolerances based on their liability structure, investment horizon, and regulatory constraints. For example, insurance companies have strict risk constraints due to regulatory requirements.

- Liquidity Needs: Institutional portfolios may have different liquidity needs. Pension funds and insurance companies may face substantial cash flow needs, whereas endowments can generally take a more long-term approach.

- Time Horizon: Institutional investors typically have long investment horizons. However, time horizons vary depending on the liability structure. For example, defined-benefit pension plans may consider the aging demographics of their beneficiaries.

- Regulatory and Legal Considerations: Each institution operates within specific regulatory frameworks. For instance, insurance companies must adhere to solvency and capital adequacy standards, while SWFs must consider sovereign concerns and political implications.

- Tax Considerations: Tax impacts vary across institutions; for instance, certain foundations, endowments, and pensions may be tax-exempt, affecting their investment strategy differently than taxable entities, which may focus on tax-efficient investments.

- Income Needs: Some institutions require steady income generation to fund operations or meet payout requirements. For instance, a pension fund may need consistent income to pay beneficiaries, influencing its asset allocation.

- Ethical and Social Responsibility Constraints: Increasingly, institutions integrate ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) criteria to align investments with specific ethical or social goals, affecting sectors or assets they may exclude or prioritize.

- Portfolio Size and Diversification Needs: Larger institutions often require significant diversification across asset classes, sectors, or geographies to manage risk effectively, while smaller institutions may have more concentrated portfolios due to their size and resource constraints.

3. Asset Allocation Strategies

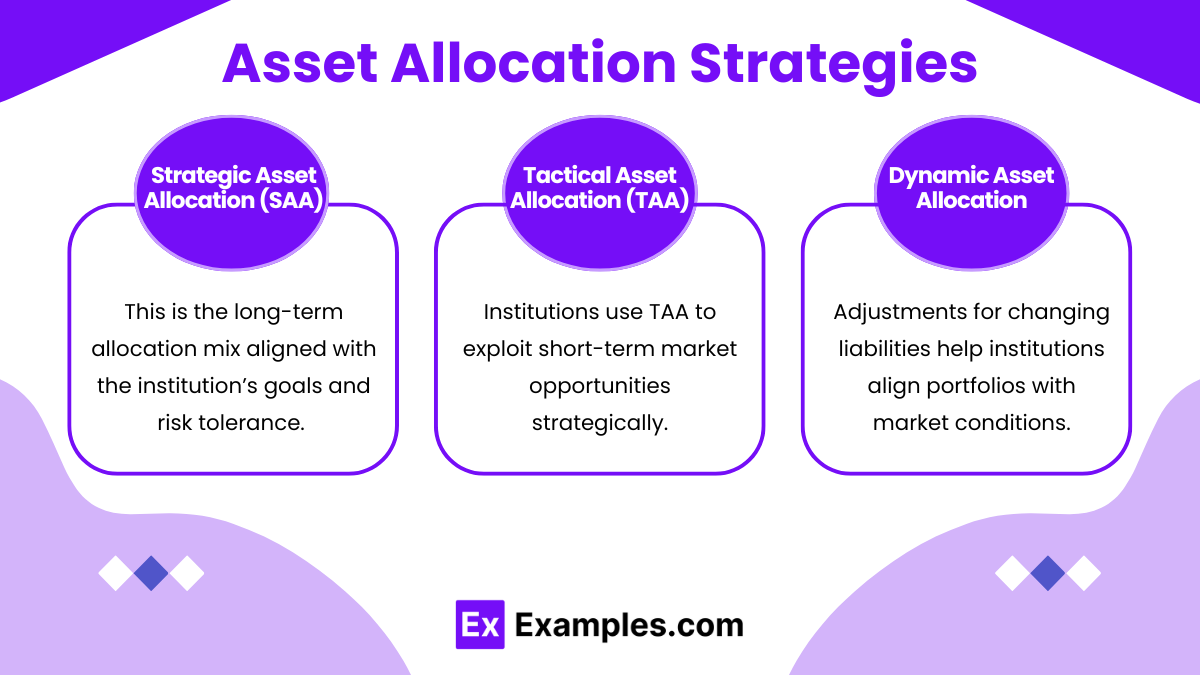

Asset allocation is a critical component in institutional portfolio management. It helps match assets with liabilities and diversify risks.

- Strategic Asset Allocation (SAA): This is the long-term allocation mix aligned with the institution’s goals and risk tolerance. It typically involves a mix of equities, fixed income, real assets, and alternative investments.

- Tactical Asset Allocation (TAA): Institutions may engage in TAA to capitalize on short-term market opportunities, adjusting the strategic allocation within certain risk parameters.

- Dynamic Asset Allocation: Adjustments based on evolving market conditions, often used by institutions like pension funds to address changing liability profiles.

4. Liability-Driven Investment (LDI) for Pension Funds

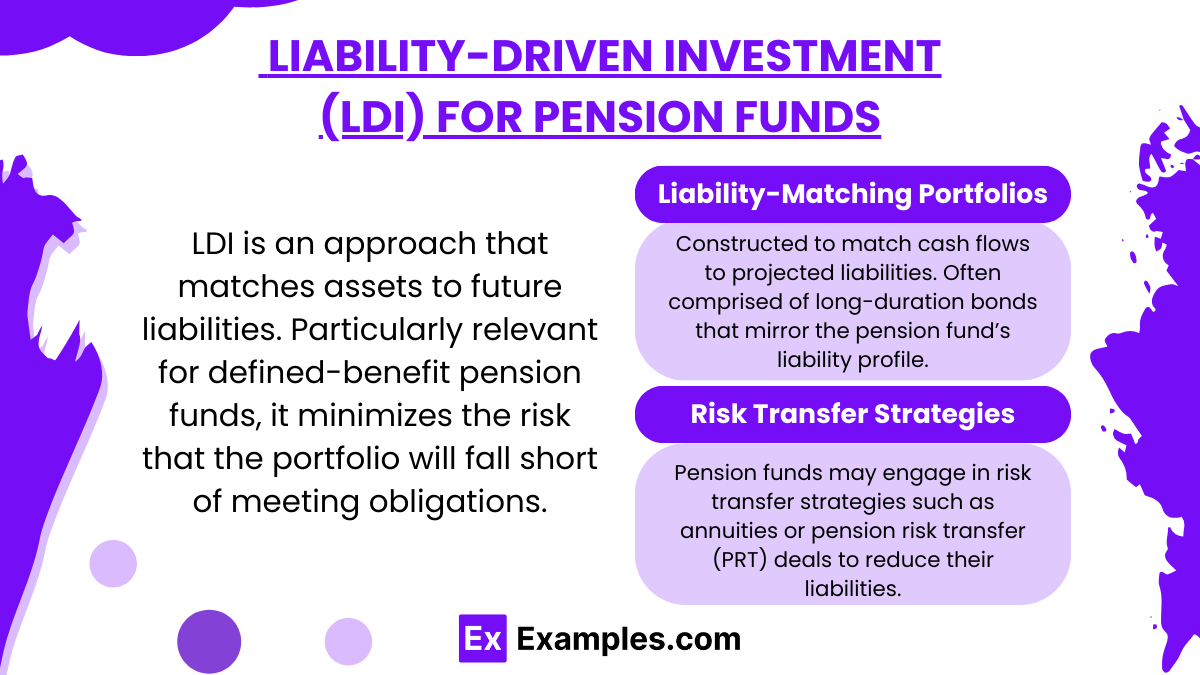

LDI is an approach that matches assets to future liabilities. Particularly relevant for defined-benefit pension funds, it minimizes the risk that the portfolio will fall short of meeting obligations.

- Liability-Matching Portfolios: Constructed to match cash flows to projected liabilities. Often comprised of long-duration bonds that mirror the pension fund’s liability profile.

- Risk Transfer Strategies: Pension funds may engage in risk transfer strategies such as annuities or pension risk transfer (PRT) deals to reduce their liabilities.

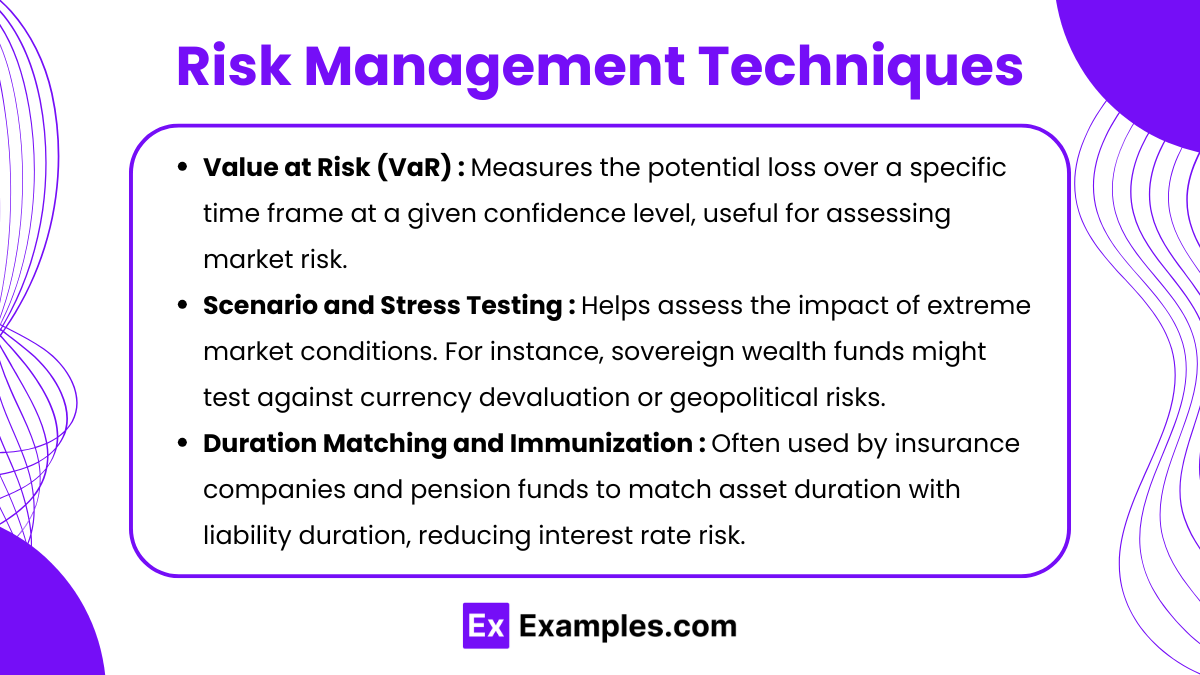

5. Risk Management Techniques

Institutions use various risk management techniques to protect against volatility, interest rate changes, and market downturns.

- Value at Risk (VaR): Measures the potential loss over a specific time frame at a given confidence level, useful for assessing market risk.

- Scenario and Stress Testing: Helps assess the impact of extreme

- market conditions. For instance, sovereign wealth funds might test against currency devaluation or geopolitical risks.

- Duration Matching and Immunization: Often used by insurance companies and pension funds to match asset duration with liability duration, reducing interest rate risk.

Examples

Example 1: Defined-Benefit Pension Fund Portfolio Management

Defined-benefit pension funds have specific liability structures and long-term obligations to provide retirement benefits. Portfolio managers for these funds focus on asset-liability matching to ensure future liabilities can be met. This often involves a liability-driven investment (LDI) strategy, where fixed-income securities with durations that match pension obligations are prioritized. Additionally, pension funds may allocate to equities and alternative assets to improve returns, balancing risk tolerance with the need for growth to cover future payouts.

Example 2: Endowment Portfolio Management

Endowments, such as those for universities or charitable institutions, aim to preserve purchasing power while generating stable returns to fund ongoing programs. This goal requires a diversified asset allocation, with a significant portion in equities for growth and alternative investments (e.g., private equity, real estate) to achieve higher returns and diversification. Endowment managers often emphasize intergenerational equity, meaning the portfolio is structured to support current and future spending needs without eroding the principal over time.

Example 3: Insurance Company Portfolio Management

Insurance companies, particularly life insurers, focus on asset-liability matching to meet future claims. Life insurers typically use long-duration bonds and investment-grade fixed income to match liabilities that extend over decades. For property and casualty insurers, the investment horizon is often shorter, and liquidity needs are higher to meet unpredictable claim demands. Both types of insurers are also regulated, with capital adequacy requirements influencing the portfolio’s risk and asset allocation, emphasizing stable, income-generating investments.

Example 4: Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF) Portfolio Management

Sovereign wealth funds, owned by governments, manage surplus reserves and are often used for economic stabilization, generational savings, or infrastructure investment. SWFs vary in their investment approaches, with some focused on higher-yield assets like equities and alternatives, while others maintain a conservative approach with significant allocations to government bonds and other fixed-income assets. SWF portfolio managers often balance political and social mandates with financial objectives, sometimes considering ESG factors as part of their investment philosophy.

Example 5: Foundation Portfolio Management

Foundations, which support specific causes or missions, typically aim to generate stable income to fund grants and other activities. Their portfolios are structured with a strong focus on capital preservation and consistent income generation. Foundation portfolios may include a mix of equities, fixed income, and alternative assets, but they often prioritize low-risk investments to ensure a reliable cash flow for funding programs. Foundations may also integrate ESG principles, aligning their investments with their mission while balancing risk and return to maintain capital over the long term.

Question 1

Which of the following is typically the primary objective of a pension fund in its portfolio management strategy?

A. Maximize returns without concern for risk.

B. Preserve capital to maintain purchasing power.

C. Match assets to future liabilities.

D. Generate high liquidity for daily expenses.

Answer: C. Match assets to future liabilities.

Explanation: Pension funds, particularly defined-benefit (DB) plans, have the primary objective of ensuring they have sufficient assets to meet future liabilities. These liabilities are the future pension payments to beneficiaries. Therefore, pension funds often employ a liability-driven investment (LDI) strategy, focusing on matching assets with expected future cash outflows. The other options are less relevant for a pension fund’s primary objectives:

- Option A (Maximize returns without concern for risk): While returns are important, pension funds must carefully manage risk to ensure they can meet future obligations.

- Option B (Preserve capital): Though capital preservation is relevant, it is typically more pertinent to endowments or foundations rather than pension funds, which prioritize matching liabilities.

- Option D (Generate high liquidity): Pension funds have relatively predictable cash flows and don’t need high liquidity for daily expenses like some other types of institutional investors, such as insurance companies.

Question 2

An endowment fund is primarily focused on maintaining purchasing power while generating a steady income for funding operations. Which of the following asset classes is most likely to be emphasized in the strategic asset allocation of an endowment fund?

A. Long-duration government bonds.

B. Cash and cash equivalents.

C. Equities and real assets.

D. High-yield bonds.

Answer: C. Equities and real assets.

Explanation: Endowments are designed to support operational funding over the long term, which requires maintaining or growing purchasing power over time. As such, endowment funds typically prioritize equities and real assets because these asset classes have historically provided returns above inflation, helping to preserve purchasing power. Additionally, real assets, like real estate or commodities, offer inflation protection. Here’s why the other options are less relevant:

- Option A (Long-duration government bonds): While they provide stability, these bonds generally have lower returns, making it challenging to maintain purchasing power over long periods.

- Option B (Cash and cash equivalents): Cash offers liquidity but yields returns below inflation, eroding purchasing power over time.

- Option D (High-yield bonds): Though they offer higher returns, high-yield bonds add credit risk, and endowments usually seek diversification with lower levels of credit risk.

Question 3

Which risk management technique is most suitable for an insurance company to address the mismatch between asset and liability durations in its portfolio?

A. Value at Risk (VaR) analysis.

B. Duration matching.

C. Tactical Asset Allocation (TAA).

D. Investing in high-yield bonds for higher returns.

Answer: B. Duration matching.

Explanation: Insurance companies, especially life insurers, face long-term liabilities and are concerned about interest rate risk due to the potential mismatch in asset and liability durations. Duration matching is a technique used to align the durations of assets and liabilities, thereby reducing interest rate risk and ensuring that assets can cover future liabilities as they become due. Let’s break down the other options:

- Option A (VaR analysis): While VaR is a valuable risk assessment tool, it doesn’t address duration mismatches. VaR measures potential loss in value under certain conditions but is more applicable to assessing overall portfolio risk.

- Option C (Tactical Asset Allocation): TAA involves adjusting allocations to capitalize on market opportunities, but it doesn’t directly address duration matching or liability alignment.

- Option D (High-yield bonds): High-yield bonds offer higher returns but increase credit risk and do not directly solve duration mismatches, which is crucial for managing interest rate sensitivity in an insurance company’s portfolio.