Futures are a core component of financial markets, providing opportunities for hedging, speculation, and portfolio diversification. This topic explores the fundamentals of futures contracts, including contract specifications, margin requirements, and the mechanics of futures trading. It also examines the role of futures markets in price discovery and risk management, along with the impact of leverage and the distinction between hedgers and speculators. A solid understanding of futures is essential for technical analysts seeking to analyze and navigate market trends, as futures play a significant role in global trading strategies and risk management practices.

Learning Objectives

In studying “Futures” for the CMT, you should learn to understand the structure and purpose of futures contracts, including their standardized nature and the role of exchanges. Analyze how futures are used for hedging and speculation, focusing on their applications in managing price risk for commodities, indices, currencies, and interest rates. Examine key terms such as margin, leverage, and mark-to-market adjustments, along with their implications for traders and investors. Understand the pricing mechanisms of futures contracts, including the impact of factors like the cost of carry and interest rates. Additionally, evaluate strategies for trading futures, such as spread trading and directional bets, and learn to apply technical analysis tools within the futures market for informed decision-making.

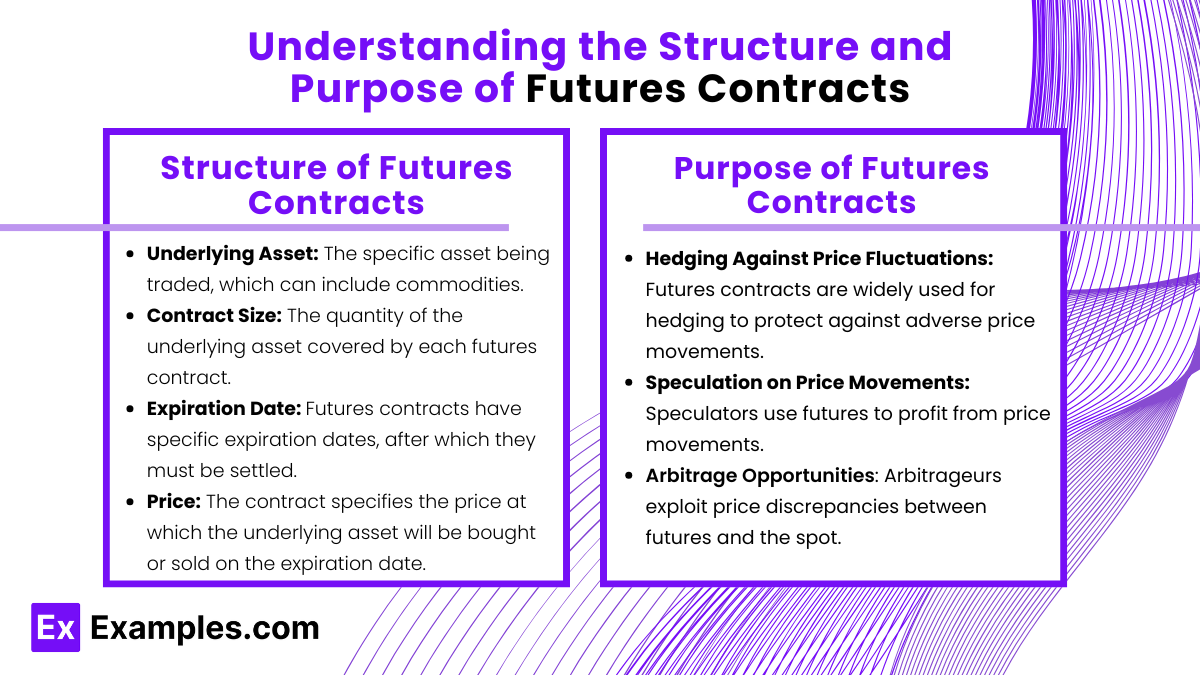

Understanding the Structure and Purpose of Futures Contracts

A futures contract is a standardized financial agreement between two parties to buy or sell an asset at a predetermined price on a specified future date. Futures contracts are essential tools in financial markets, primarily used for hedging, speculation, and portfolio diversification. Here’s an overview of the structure of futures contracts and their purpose in investment and risk management.

1. Structure of Futures Contracts

Futures contracts are highly standardized, specifying key terms to ensure uniformity and easy trading on futures exchanges. Here are the key components of a futures contract:

- Underlying Asset: The specific asset being traded, which can include commodities (e.g., oil, gold, corn), financial instruments (e.g., currency, stock indices, interest rates), or digital assets. Each futures contract is linked to a particular asset, defining what the buyer will receive or the seller will deliver.

- Contract Size: The quantity of the underlying asset covered by each futures contract. For example, one crude oil futures contract on the CME covers 1,000 barrels of oil. This standardization ensures transparency and ease of trading.

- Expiration Date: Futures contracts have specific expiration dates, after which they must be settled. Expiration can vary by contract type (e.g., monthly, quarterly). Traders typically close or roll over positions before the expiration date to avoid physical delivery (if not desired).

- Price: The contract specifies the price at which the underlying asset will be bought or sold on the expiration date. This price fluctuates based on market supply and demand, enabling buyers and sellers to “lock in” a price.

- Settlement Method: Futures can be settled either by physical delivery or cash settlement. Physical delivery means the buyer takes possession of the asset at expiration (common with commodities). Cash settlement means that, upon expiration, parties settle the difference in price rather than transferring the asset (common with financial futures like stock indices).

- Margin Requirements: Traders are required to post an initial margin (a fraction of the contract’s value) and maintain a minimum margin (maintenance margin) throughout the contract. Margins act as collateral to mitigate credit risk and ensure contract performance.

Example: A gold futures contract on the COMEX represents 100 troy ounces of gold. If an investor buys a futures contract at $1,800 per ounce, they agree to buy 100 ounces at this price on the contract’s expiration date.

2. Purpose of Futures Contracts

Futures contracts serve various purposes, benefiting different types of market participants, including hedgers, speculators, and arbitrageurs. Here’s a look at the main purposes of trading futures:

- Hedging Against Price Fluctuations: Futures contracts are widely used for hedging to protect against adverse price movements. By locking in a price for a future date, businesses and investors can stabilize costs or revenues, reducing exposure to volatile markets.

- Example: A wheat farmer may sell wheat futures to lock in a selling price, protecting against the risk of falling wheat prices. Conversely, a bakery may buy wheat futures to secure a buying price, protecting against the risk of rising wheat prices.

- Speculation on Price Movements: Speculators use futures to profit from price movements without intending to own the underlying asset. They buy futures if they expect prices to rise or sell (short) if they expect prices to fall. Futures are popular for speculation because they allow high leverage, meaning traders can control large positions with a relatively small margin.

- Example: An investor who expects crude oil prices to increase may buy oil futures. If prices rise by expiration, they can sell the contract at a higher price, profiting from the difference.

- Arbitrage Opportunities: Arbitrageurs exploit price discrepancies between futures and the spot (current) price of the underlying asset. They aim to make risk-free profits by simultaneously buying and selling assets in different markets where price differences exist.

- Example: If the futures price of gold is higher than the spot price, an arbitrageur might buy gold in the spot market and sell gold futures, profiting as prices converge.

- Price Discovery: Futures markets contribute to price discovery by reflecting market participants’ expectations for the future price of an asset. The futures price provides valuable information about anticipated supply, demand, and other market factors.

- Example: If oil futures are priced significantly higher than the current spot price, it may indicate expected future supply constraints or rising demand for oil.

- Efficient Portfolio Management and Diversification: Futures allow investors to gain exposure to various asset classes (e.g., commodities, currencies) for diversification without directly purchasing the assets. Portfolio managers use futures to adjust asset allocation quickly, manage risk, and reduce transaction costs compared to buying physical assets.

- Example: A portfolio manager seeking exposure to gold might buy gold futures instead of holding physical gold, benefiting from lower costs and easier execution.

Applications of Futures for Hedging and Speculation

Futures contracts are versatile tools with two primary applications: hedging and speculation. Here’s how each application works and why it’s beneficial for various types of market participants.

1. Futures for Hedging

Hedging with futures helps entities protect against the financial impact of unfavorable price changes. This is particularly useful for businesses exposed to fluctuations in the prices of commodities, interest rates, or foreign exchange.

- Commodity Producers: Farmers and miners often use futures to lock in prices for their products, securing revenue even if market prices fall. For example, a wheat farmer may sell wheat futures before the harvest to guarantee a specific sale price, protecting against potential declines in wheat prices.

- Manufacturers and Consumers: Businesses that rely on commodities (like airlines using jet fuel) use futures to lock in prices and stabilize expenses. An airline, for example, might buy fuel futures to protect against rising oil prices, ensuring consistent operating costs.

- Financial Institutions: Banks and financial firms often use futures to hedge interest rate and currency risks. For instance, a U.S.-based company expecting payments in euros may use currency futures to lock in the exchange rate, protecting itself from adverse currency movements.

Example of Hedging with Futures: Suppose a coffee company anticipates rising coffee prices in the next six months. To secure current prices, the company purchases coffee futures, locking in the price it will pay. If coffee prices rise, the futures contract offsets the additional cost, as the company effectively pays the pre-set price.

2. Futures for Speculation

Speculation involves trading futures contracts to profit from anticipated price changes rather than to hedge existing exposure. Speculators aim to buy low and sell high (or vice versa), using leverage to magnify returns.

- Price Movement Predictions: Speculators bet on future price directions. For example, if a trader expects oil prices to increase, they may buy oil futures. If prices rise as anticipated, they can sell the contract at a higher price, profiting from the difference.

- Leverage for Higher Returns: Futures contracts allow traders to control large amounts of the asset with a relatively small initial investment (known as margin). This leverage can amplify gains, though it also increases the risk of losses.

- Short-Selling Opportunities: Speculators can short-sell futures to profit from anticipated declines in asset prices. For example, if a trader expects the price of corn to drop, they can sell corn futures and buy them back at a lower price if the market moves as predicted.

Example of Speculating with Futures: A trader believes that gold prices will rise over the next month. They buy a gold futures contract at the current price of $1,800 per ounce. If gold’s price increases to $1,850, the trader can sell the contract at a profit. Conversely, if the price falls, they may incur a loss.

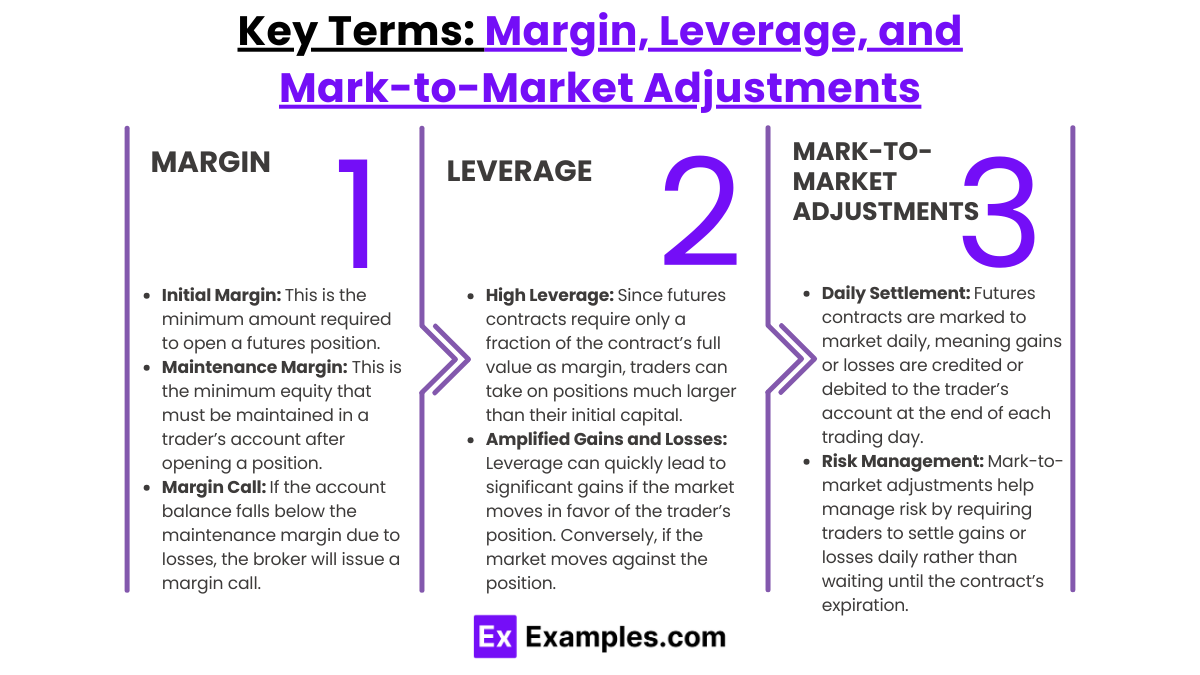

Key Terms: Margin, Leverage, and Mark-to-Market Adjustments

Futures contracts involve specific financial concepts that are essential to managing risk and maximizing potential returns. Three key terms in futures trading are margin, leverage, and mark-to-market adjustments. Each plays a significant role in how futures contracts are traded, how much capital is required, and how profits or losses are calculated on a daily basis. Here’s a closer look at each of these terms and their importance in futures trading.

1. Margin

In futures trading, margin refers to the initial amount of money that traders must deposit to enter a position, which serves as a performance bond rather than a down payment. Unlike in stock trading, where margin is borrowed money, futures margin is a good-faith deposit that ensures the trader can cover potential losses.

- Initial Margin: This is the minimum amount required to open a futures position. It is typically a small percentage of the contract’s total value (often between 3-10%) and varies by asset and market conditions.

- Maintenance Margin: This is the minimum equity that must be maintained in a trader’s account after opening a position. If the account balance falls below the maintenance margin due to market losses, the trader receives a margin call and must deposit additional funds to restore the initial margin level.

- Margin Call: If the account balance falls below the maintenance margin due to losses, the broker will issue a margin call. The trader must add funds to meet the initial margin requirement or risk having their position closed by the broker.

Example: Suppose a trader opens a position in a futures contract with a $10,000 initial margin requirement and a $7,000 maintenance margin. If losses reduce the account balance below $7,000, the trader will receive a margin call to bring the balance back up to $10,000.

2. Leverage

Leverage in futures trading refers to the ability to control a large contract value with a relatively small margin deposit. This allows traders to amplify potential returns, as small price movements can result in substantial gains or losses. However, leverage also increases risk, as losses are magnified just as much as profits.

- High Leverage: Since futures contracts require only a fraction of the contract’s full value as margin, traders can take on positions much larger than their initial capital. This high leverage is attractive to speculators but can be risky due to the potential for large losses.

- Amplified Gains and Losses: Leverage can quickly lead to significant gains if the market moves in favor of the trader’s position. Conversely, if the market moves against the position, losses can exceed the initial margin, potentially leading to margin calls or forced liquidation.

Example: A trader with $10,000 might control a futures contract worth $100,000 due to leverage. A 1% increase in the contract’s value could yield a $1,000 profit, while a 1% decrease could lead to a $1,000 loss, demonstrating how leverage amplifies returns and risks.

3. Mark-to-Market Adjustments

Mark-to-market (MTM) is the daily process of adjusting the value of a futures contract to reflect changes in the market price. Each trading day, profits and losses are settled between buyers and sellers, ensuring that account balances reflect the contract’s current market value.

- Daily Settlement: Futures contracts are marked to market daily, meaning gains or losses are credited or debited to the trader’s account at the end of each trading day. If the market moves favorably, the trader’s account balance increases; if it moves unfavorably, the balance decreases.

- Risk Management: Mark-to-market adjustments help manage risk by requiring traders to settle gains or losses daily rather than waiting until the contract’s expiration. This ensures that losses don’t accumulate beyond what the trader can afford, and it helps brokers monitor risk in clients’ accounts.

Example: If a trader’s futures position gains $500 during the day, their account is credited with $500 through mark-to-market adjustment. If the position loses $500 the next day, that amount is debited. This ongoing settlement ensures that account balances reflect market value fluctuations.

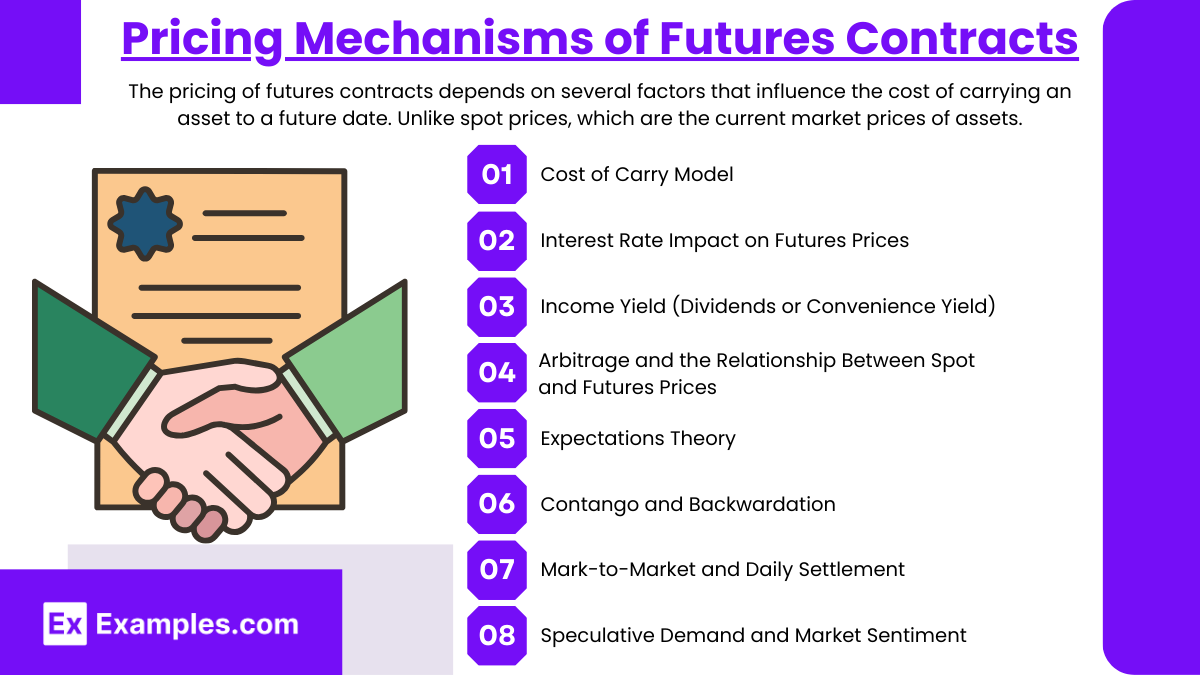

Pricing Mechanisms of Futures Contracts

The pricing of futures contracts depends on several factors that influence the cost of carrying an asset to a future date. Unlike spot prices, which are the current market prices of assets, futures prices are determined by the expected future value of an asset and factors that affect this value over time. Here’s a look at the key mechanisms and factors involved in pricing futures contracts.

1. Cost of Carry Model

The Cost of Carry Model is the fundamental pricing mechanism for futures. This model assumes that the futures price is equal to the spot price plus the cost of carrying the asset until the contract’s expiration. The carrying cost includes storage costs, interest costs (opportunity cost of holding the asset), and any income generated by the asset (such as dividends for stocks or convenience yield for commodities).

Futures Price = Spot Price+Cost of CarryIn mathematical terms:

F = S × (1+r−y)T

where:

- F = Futures Price

- S = Spot Price

- r = Risk-free interest rate

- y = Yield on the asset (like dividends or convenience yield)

- T = Time to maturity of the futures contract

The model adjusts the futures price based on how much it would cost to hold or carry the asset until the contract’s expiration date.

2. Interest Rate Impact on Futures Prices

Interest rates play a crucial role in futures pricing, particularly for financial futures and commodities. When interest rates are high, the cost of carry for an asset rises, which increases the futures price. Conversely, when interest rates are low, the futures price decreases.

- For Financial Assets: Higher interest rates increase the cost of holding cash or investing in interest-earning securities, leading to a higher futures price.

- For Physical Commodities: High-interest rates raise storage costs, increasing the cost of carry and thus the futures price.

3. Income Yield (Dividends or Convenience Yield)

Income yield, which includes dividends for stocks or convenience yield for commodities, affects futures prices by providing a benefit to holding the asset. Convenience yield reflects the benefits of holding a commodity, especially during times of scarcity. Higher income yield can reduce the cost of carry, which lowers the futures price.

- Dividends for Stocks: For stock index futures, the expected dividend yield during the contract period reduces the cost of carry, lowering the futures price.

- Convenience Yield for Commodities: Commodities like oil, gold, or grain may have a convenience yield when holding the physical asset offers benefits, such as the ability to use or sell the asset quickly in the event of scarcity.

4. Arbitrage and the Relationship Between Spot and Futures Prices

Arbitrage opportunities arise if there’s a significant discrepancy between the spot price and the futures price. Traders can exploit this price difference by buying the cheaper asset and selling the more expensive one to lock in a risk-free profit. Arbitrage activities usually align the futures price with the cost of carry model, as arbitrage pressures drive prices back in line with theoretical expectations.

- Cash-and-Carry Arbitrage: When the futures price is higher than expected, traders can buy the spot asset, carry it to the futures expiration, and sell a futures contract. This action brings the futures price closer to the spot price plus the cost of carry.

- Reverse Cash-and-Carry Arbitrage: When the futures price is below expectations, traders can short-sell the asset, invest the proceeds, and buy a futures contract, aligning the prices.

5. Expectations Theory

The Expectations Theory suggests that futures prices represent the market’s expectation of the future spot price of an asset. This theory argues that futures prices reflect all available information and are determined by market participants’ consensus on where prices are headed.

- Bullish Market: In a market where participants expect prices to rise, the futures price may be higher than the spot price, leading to contango.

- Bearish Market: In a market where participants expect prices to fall, the futures price may be lower than the spot price, resulting in backwardation.

6. Contango and Backwardation

Contango and backwardation are terms that describe the shape of the futures curve (the relationship between futures prices and the time to expiration).

- Contango: When the futures price is higher than the current spot price. This situation is common when there are high carrying costs or expectations of rising prices in the future. In contango, traders may expect the asset’s spot price to converge toward the futures price as expiration approaches.

- Backwardation: When the futures price is lower than the current spot price. This usually occurs in markets with high convenience yield or anticipated short-term shortages. Traders expect the spot price to fall towards the futures price over time in backwardation.

7. Mark-to-Market and Daily Settlement

Futures contracts are marked-to-market daily, meaning gains and losses are realized on a daily basis. This impacts futures pricing as market participants are compensated or penalized for daily price changes, which can influence trading behaviors and the cost of maintaining futures positions over time.

- Mark-to-Market Adjustments: Each trading day, the contract price is adjusted to reflect the current market price, crediting or debiting the trader’s margin account accordingly. This daily settlement affects the pricing and attractiveness of futures contracts, as traders may need to maintain sufficient margin to cover potential losses.

8. Speculative Demand and Market Sentiment

The demand from speculators can impact futures prices, especially in commodities and financial futures markets. Market sentiment—whether bullish or bearish—can drive prices above or below fundamental values based on supply and demand, causing temporary deviations from theoretical prices.

- Speculative Demand: When more speculators expect prices to rise, they buy futures contracts, pushing prices higher. Conversely, selling pressure from speculators expecting a decline can drive futures prices lower.

- Impact on Futures Prices: Although speculative demand can cause short-term fluctuations, the futures price tends to converge with the expected spot price as the expiration date approaches.

Examples

Example 1: Commodity Futures

Commodity futures are contracts to buy or sell a specific quantity of a commodity, like oil or wheat, at a predetermined price on a future date. These are commonly used by producers and consumers of commodities to hedge against price fluctuations. For instance, an airline company might use jet fuel futures to lock in current fuel prices and avoid volatility.

Example 2: Stock Index Futures

Stock index futures allow investors to speculate on the future direction of stock market indices like the S&P 500 or Dow Jones. These contracts provide exposure to the overall performance of a stock market index rather than individual stocks. They are used by institutional investors for hedging and by traders to profit from anticipated market movements.

Example 3: Interest Rate Futures

Interest rate futures are financial contracts used by investors to hedge against or speculate on changes in interest rates. For example, a bondholder might use interest rate futures to protect against the risk of rising interest rates, which could lead to falling bond prices. These futures are widely used by banks and other financial institutions.

Example 4: Currency Futures

Currency futures are contracts that allow traders to buy or sell a specific amount of a foreign currency at a future date. These contracts are used by companies that deal with international trade to manage the risk of currency fluctuations. For example, a European company exporting goods to the U.S. might use U.S. dollar futures to protect against a potential drop in the value of the dollar.

Example 5: Agricultural Futures

Agricultural futures involve contracts based on agricultural products like corn, soybeans, or coffee. These futures allow farmers to lock in prices for their crops ahead of time, protecting against the risk of price drops during harvest. Similarly, buyers of agricultural goods use these contracts to hedge against potential price increases.

Practice Questions

Question 1

What is the primary purpose of using futures contracts?

A) To speculate on the future price movements of assets

B) To avoid paying taxes on investments

C) To guarantee a profit from an investment

D) To increase the value of underlying assets

Correct Answer: A) To speculate on the future price movements of assets.

Explanation: Futures contracts are primarily used by investors and traders to speculate on the future price movements of assets such as commodities, stock indices, or currencies. They allow participants to profit from anticipated changes in price. While they can also be used for hedging against price fluctuations, the main purpose is speculation on price movements. Option B and D are incorrect as futures do not directly influence taxes or asset values, and C is false because futures do not guarantee profits, they only offer the potential for profit or loss.

Question 2

Which of the following is a characteristic of futures contracts?

A) They are usually customized to fit the specific needs of the buyer and seller.

B) They require the buyer to take physical delivery of the underlying asset.

C) They are standardized contracts traded on exchanges.

D) They have no expiration date.

Correct Answer: C) They are standardized contracts traded on exchanges.

Explanation: Futures contracts are standardized agreements that specify the quality, quantity, and settlement date of the underlying asset. These contracts are traded on futures exchanges, which help to ensure liquidity and standardized terms for both buyers and sellers. Unlike forward contracts, which can be customized, futures are highly regulated and standardized. Option B is not always true, as many futures contracts are cash-settled, meaning no physical delivery is required. Option D is incorrect because futures contracts always have a specified expiration date.

Question 3

Who typically uses futures contracts?

A) Only speculators who aim to profit from price movements.

B) Only large institutional investors.

C) Producers and consumers who wish to hedge against price fluctuations.

D) Only individuals who want to invest in the underlying assets directly.

Correct Answer: C) Producers and consumers who wish to hedge against price fluctuations.

Explanation: Futures contracts are commonly used by producers and consumers in various industries to hedge against the risk of price fluctuations in commodities or financial instruments. For example, a farmer might use futures contracts to lock in the price for their crops, ensuring that they are protected from price drops. While speculators also use futures for potential profits, the hedging function is a major purpose for these contracts. Option A and D focus too narrowly on speculation and direct investment, respectively, while option B excludes other market participants who use futures for risk management.