The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) is a foundational theory in finance, asserting that financial markets are “informationally efficient.” According to EMH, asset prices reflect all available information, making it challenging to consistently achieve above-average returns. Understanding EMH aids in evaluating market behavior, investment strategies, and price fluctuations, vital for success in the CMT Exam.

Learning Objectives

In studying “Efficient Market Hypothesis” (EMH) for the CMT Exam, you should learn to understand the core principles that define market efficiency, including the three forms of EMH: weak, semi-strong, and strong. Examine how EMH posits that asset prices incorporate all available information, affecting the predictability of stock price movements. Evaluate the implications of EMH on technical and fundamental analysis, and explore how market anomalies challenge or support this hypothesis. Apply your understanding of EMH to assess investment strategies, interpret price patterns, and analyze whether historical data provides any edge in achieving superior returns in efficient markets.

What is the Efficient Market Hypothesis?

The Efficient Market Hypothesis is a cornerstone of financial theory, asserting that financial markets are “informationally efficient.” This theory suggests that asset prices at any given time reflect all available information, making it nearly impossible to consistently achieve higher-than-average returns without assuming additional risk. Understanding EMH is essential for analyzing market behavior and evaluating the effectiveness of different investment strategies.

The Three Forms of EMH

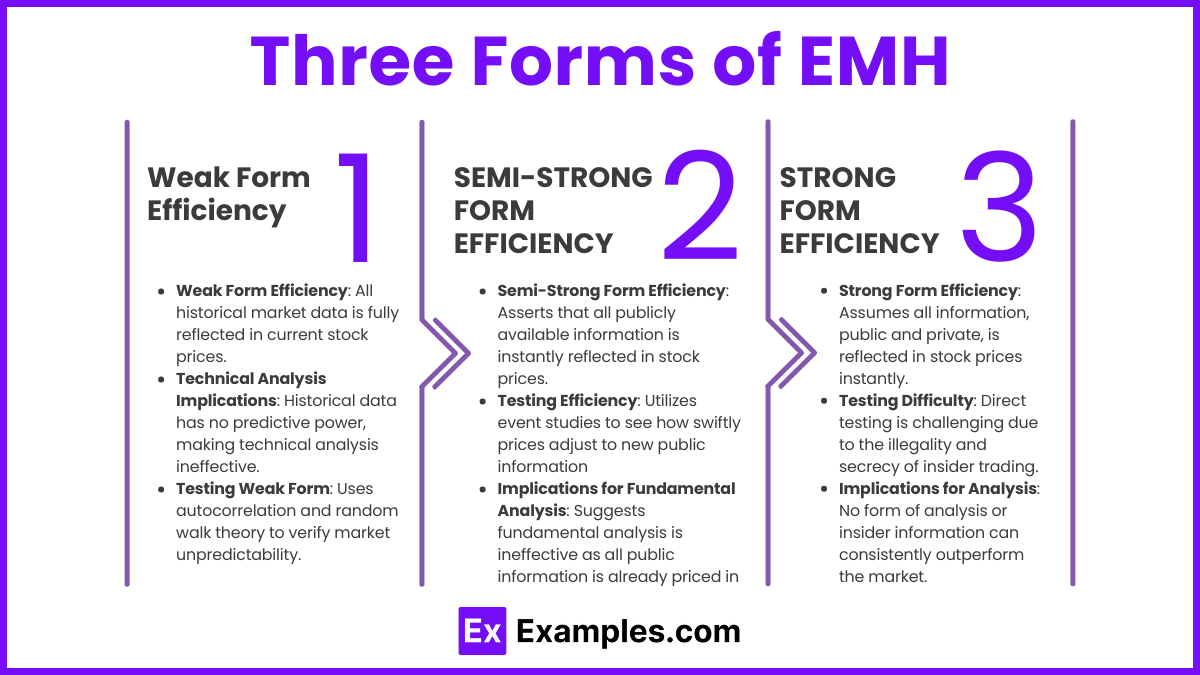

1. Weak Form Efficiency

Weak form efficiency suggests that all historical price data, including past prices, volume, and other market data, are fully reflected in current stock prices. According to this form:

- Implications for Technical Analysis: Since historical data is already incorporated into prices, technical analysis—which relies on past price trends, volume patterns, and other indicators—should have no predictive power. Proponents of weak form efficiency argue that any patterns, such as support and resistance levels or moving averages, are essentially random and cannot be used to gain an advantage in predicting future price movements.

- Testing Weak Form Efficiency: Market efficiency in this form is often tested using statistical methods like autocorrelation tests, which check if past price changes are correlated with future price changes. Another test involves the random walk theory, which posits that price movements are random and therefore unpredictable.

- Criticism and Market Anomalies: While weak form efficiency suggests that historical data holds no value for forecasting, some studies argue that certain momentum and reversal effects contradict this. For example, in certain markets, stocks that performed well in the past continue to perform well for a short period (momentum), which challenges the weak form of EMH.

2. Semi-Strong Form Efficiency

Semi-strong form efficiency asserts that all publicly available information is reflected in stock prices. This includes not only past price and volume data but also all publicly disclosed information, such as:

- Corporate Announcements: Earnings reports, dividends, stock splits, and mergers/acquisitions.

- Economic Indicators: Inflation rates, unemployment data, interest rates, and GDP figures.

- News and Media Reports: Any information accessible to the general public, including news, analyst reports, and market commentary.

Under semi-strong efficiency:

- Implications for Fundamental Analysis: If the market is semi-strong efficient, fundamental analysis—which involves examining financial statements, economic indicators, and industry trends—should not yield an advantage. Since all public information is already priced in, buying or selling based on such information should not generate above-average returns.

- Event Studies: The semi-strong form is often tested using event studies, which examine how stock prices react to new public information. For example, researchers might study how quickly a stock price adjusts following an earnings announcement. If prices adjust almost instantly, it supports semi-strong form efficiency.

- Market Anomalies and Criticisms: Certain anomalies challenge semi-strong efficiency. For instance, the January Effect suggests that stocks, particularly smaller-cap stocks, tend to outperform in January. Another example is post-earnings announcement drift, where stock prices continue to move in the direction of an earnings surprise for days or even weeks after the announcement, suggesting that prices do not fully adjust immediately to new information.

3. Strong Form Efficiency

Strong form efficiency suggests that all information—both public and private (insider information)—is reflected in stock prices. In this scenario, even individuals with access to insider knowledge, such as executives or board members, cannot consistently achieve returns above the average market return.

- Implications for All Forms of Analysis: Strong form efficiency implies that neither technical analysis, fundamental analysis, nor even insider information can provide a trading advantage. Every piece of information, regardless of its nature, is assumed to be instantly priced into the asset, making it impossible to “beat the market” even with privileged information.

- Testing Strong Form Efficiency: Strong form efficiency is difficult to test directly because insider trading is typically illegal, and insiders rarely share information openly. However, studies occasionally look at the returns of corporate insiders (through filings required by regulatory bodies) to see if they consistently outperform. A lack of abnormal returns for insiders would support strong form efficiency.

- Criticism and Market Anomalies: Evidence generally does not support strong form efficiency. Studies have shown that insiders, when they buy or sell their own company’s stock, often achieve above-average returns. This contradicts the idea that all information is reflected in stock prices, suggesting that strong form efficiency may not hold in real markets.

Implications for Technical and Fundamental Analysis

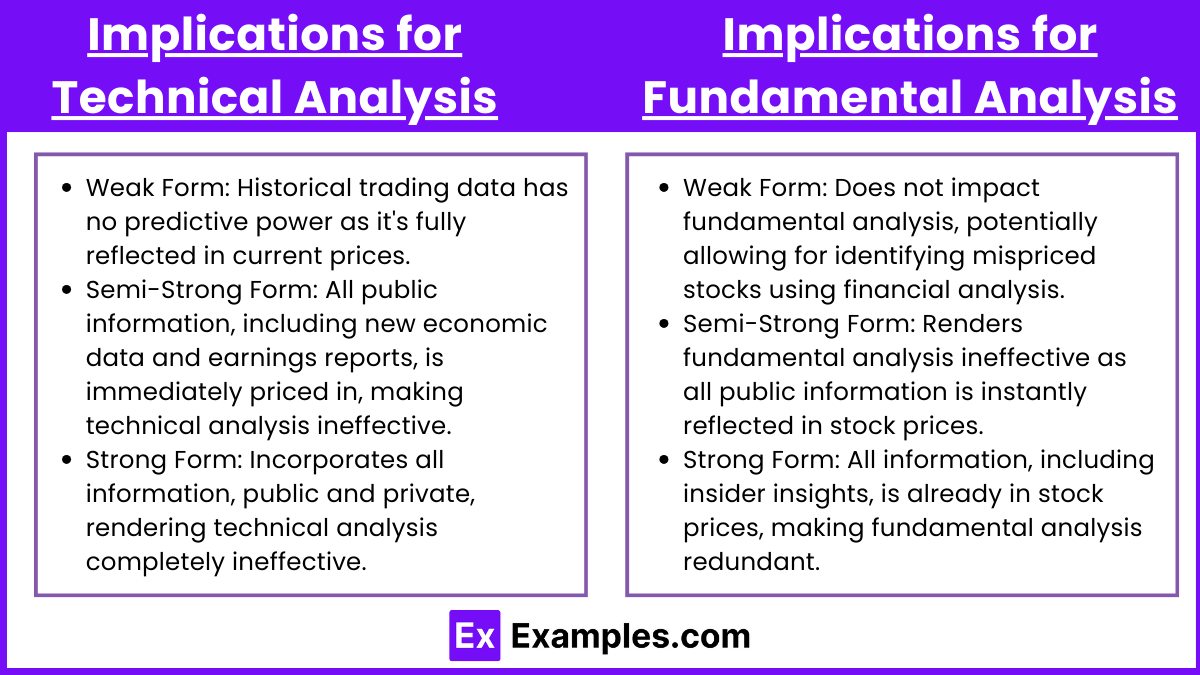

1. Implications for Technical Analysis

Technical analysis involves studying historical price patterns, trading volumes, and market indicators to forecast future price movements. However, each form of EMH challenges the usefulness of technical analysis in different ways:

- Weak Form Efficiency: Since weak form efficiency suggests that all past trading information, including prices and volumes, is already reflected in current stock prices, technical analysis should theoretically offer no advantage. According to this view, patterns like support and resistance levels, moving averages, or trend lines would not help predict future prices, as any insights from historical data are already “priced in.” This would mean that price movements follow a random walk, and technical indicators cannot consistently predict future movements.

- Semi-Strong Form Efficiency: In addition to historical prices, semi-strong efficiency asserts that all publicly available information is also fully reflected in stock prices. Therefore, technical analysis is even less effective in a semi-strong efficient market because not only is historical data reflected in prices, but any new information—earnings reports, industry news, or economic indicators—immediately impacts prices as well. Consequently, technical analysts would find it challenging to capitalize on price patterns before the market adjusts to new information.

- Strong Form Efficiency: Strong form efficiency posits that all information, both public and private, is already incorporated into stock prices. In this case, not only does technical analysis become ineffective, but even insiders with privileged information cannot consistently achieve above-average returns. For technical analysts, this means that every piece of information—visible or concealed—is already reflected in the price, making it nearly impossible to gain an edge through chart patterns or technical signals.

2. Implications for Fundamental Analysis

Fundamental analysis focuses on evaluating a company’s financial health, industry position, and economic factors to determine its intrinsic value and identify potential mispricings in the market. EMH affects the effectiveness of fundamental analysis as follows:

- Weak Form Efficiency: Weak form efficiency does not directly affect fundamental analysis since it only considers historical price data. Proponents of weak form efficiency argue that fundamental analysis may still uncover undervalued or overvalued stocks, as this form does not assume that all public information is fully reflected in prices. Fundamental analysis could still potentially identify mispricings based on a company’s financial statements, industry trends, or economic factors.

- Semi-Strong Form Efficiency: Semi-strong efficiency suggests that all publicly available information, including financial reports, news, and economic data, is instantly reflected in stock prices. As a result, fundamental analysis would also be ineffective in providing a consistent advantage, as any insights derived from public information are already factored into current prices. Investors who use financial reports, ratios, and forecasts would have little opportunity to profit from this information, as the market has already “priced in” these factors.

- Strong Form Efficiency: Strong form efficiency posits that all information, including insider data, is already accounted for in stock prices. This implies that even insiders cannot consistently achieve superior returns. In a strongly efficient market, fundamental analysis would be entirely redundant, as all public and private information is believed to be reflected in prices. The implications for fundamental analysts are significant: if this form of EMH held, then studying company fundamentals, industry reports, and economic indicators would not yield any investment advantage.

Market Anomalies and Criticisms of EMH

Despite its widespread acceptance, the EMH faces criticism due to observed market anomalies that appear to contradict it:

1. Behavioral Anomalies

Behavioral finance challenges EMH by suggesting that investors do not always act rationally. Various cognitive biases can cause irrational market behavior, resulting in mispricing and deviations from efficient market theory. Key behavioral anomalies include:

- Overconfidence and Overreaction: Investors may become overconfident in their analysis or forecasts, leading to excessive trading and pushing prices away from their fundamental values. Overreaction occurs when investors overemphasize recent information, causing price swings that are larger than justified by fundamentals.

- Herd Behavior: Investors sometimes follow the crowd or mimic the decisions of others, creating trends or bubbles. This herd mentality can lead to market bubbles, where prices inflate beyond their true value, only to later crash as sentiment shifts.

- Loss Aversion and Prospect Theory: People are more sensitive to losses than to gains of equal size, which can lead to risk-averse behavior in bull markets and overly cautious or panic-driven selling during downturns. This behavior can cause short-term inefficiencies in pricing.

These behavioral tendencies contradict EMH by indicating that prices may not always reflect all available information, especially when investors make irrational decisions based on psychological biases.

2. Seasonal and Calendar Effects

Certain predictable patterns in stock performance appear tied to specific times of the year, which contradicts the random price movement suggested by EMH. Common calendar anomalies include:

- January Effect: Stocks, particularly small-cap stocks, tend to perform better in January than in other months. This may be due to tax-loss harvesting at year-end, where investors sell losing stocks to offset gains and then reinvest in January, driving up prices.

- Weekend Effect: Historically, stock returns on Mondays have been lower than other days, possibly due to investors processing negative news over the weekend. This phenomenon contradicts the idea of efficient markets, as investors could theoretically exploit this trend by timing trades around weekends.

- Holiday Effect: Stocks often experience higher returns on the trading day before a holiday, potentially due to positive sentiment and low trading volumes. If EMH held strictly, these effects would be arbitraged away and wouldn’t persist.

These calendar-based patterns suggest that there may be recurring inefficiencies in the market, providing opportunities for savvy investors to exploit these predictable cycles.

3. Momentum and Reversal Effects

Momentum and reversal effects present anomalies that are difficult to explain under EMH:

- Momentum Effect: Stocks that have performed well over the past 3 to 12 months tend to continue performing well in the short term. This goes against the weak form of EMH, which asserts that past performance should have no bearing on future returns. Momentum strategies exploit this trend by buying recent winners and selling recent losers.

- Long-Term Reversal Effect: In contrast to momentum, the long-term reversal effect suggests that stocks performing poorly over the long term (e.g., three to five years) may rebound, while high performers might experience declines. This phenomenon may occur as prices overreact to information, then eventually correct, which contradicts EMH’s assertion of rational pricing.

These effects indicate that historical price movements may, to some extent, be useful in predicting future prices, challenging the weak form of EMH.

4. Value and Growth Anomalies

Value and growth investing strategies contradict EMH by suggesting that certain stocks consistently outperform based on intrinsic factors:

- Value Anomaly: Research has shown that “value” stocks—those with low price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios, low price-to-book (P/B) ratios, or high dividend yields—tend to outperform “growth” stocks over the long term. This challenges EMH, as value stocks should be accurately priced if markets are truly efficient.

- Growth Anomaly: Conversely, “growth” stocks, or stocks with high expected future earnings, often trade at higher valuations but also experience strong returns. EMH would argue that high expected growth rates are already factored into stock prices, and thus, growth stocks shouldn’t systematically outperform. However, some growth stocks do, suggesting inefficiencies.

These anomalies imply that certain financial ratios and metrics can offer insight into future performance, which would not be possible if markets were fully efficient.

5. Post-Earnings Announcement Drift (PEAD)

Post-Earnings Announcement Drift is a phenomenon where a company’s stock price continues to move in the direction of an earnings surprise (either positive or negative) for days or even weeks after the announcement. This drift contradicts EMH, particularly the semi-strong form, which states that new information should be instantly reflected in stock prices.

- Causes of PEAD: PEAD may occur because investors underreact to earnings announcements, or because they do not fully process or trust the information immediately. As the market gradually digests the news, the stock price continues to adjust in the direction of the surprise.

This delayed response to public information contradicts semi-strong efficiency, as it suggests that investors could profit by buying stocks after positive earnings surprises and selling them after negative ones.

6. Criticisms of EMH

Several key criticisms challenge the validity of EMH:

- Irrational Investors: EMH assumes rational behavior, yet many studies show that investors are often irrational, driven by emotions and psychological biases. Behavioral finance has provided substantial evidence of irrational investor behavior, which can lead to mispricings.

- Overreaction and Underreaction: EMH assumes that prices instantly and accurately reflect new information. However, empirical evidence shows that investors sometimes overreact or underreact to news, causing prices to overshoot or lag.

- Market Bubbles and Crashes: The existence of bubbles (e.g., dot-com bubble, housing bubble) and sudden market crashes challenges EMH. In efficient markets, such irrational price surges or dramatic declines shouldn’t occur, as prices should reflect intrinsic values.

- Institutional Investors and Market Influence: EMH assumes a large number of independent investors, yet institutional investors like mutual funds, hedge funds, and banks can significantly influence prices. Their large trades and coordinated strategies can create distortions that challenge market efficiency.

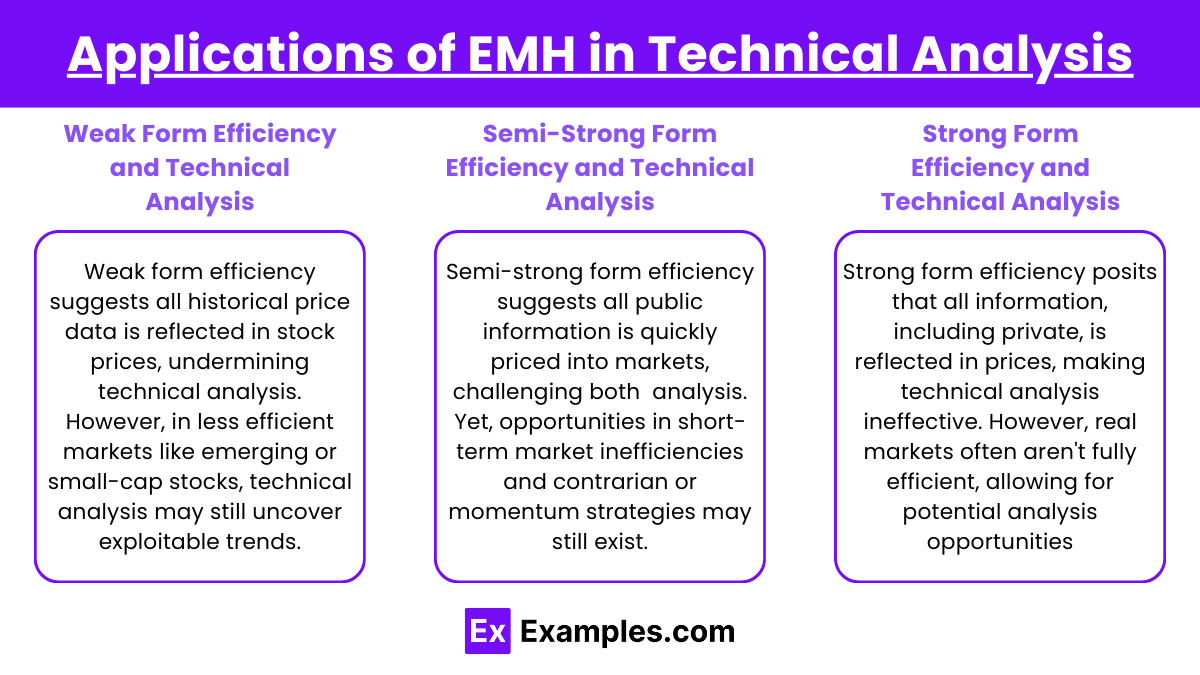

Applications of EMH in Technical Analysis

The EMH presents both challenges and opportunities for technical analysts, who rely on historical price and volume data to predict future price movements. Here’s how each form of EMH impacts technical analysis:

- Weak Form Efficiency and Technical Analysis

Weak form efficiency, which states that all past price and volume information is already reflected in current prices, directly challenges the premise of technical analysis. If weak form efficiency holds, then patterns like moving averages, trend lines, and momentum indicators should not provide a consistent advantage, as all historical data is supposedly priced in. However:- Testing Weak Form Efficiency: Technical analysts often conduct tests, such as autocorrelation studies and random walk tests, to assess whether markets truly follow a random walk. In certain markets, weak form inefficiencies may exist, allowing technical strategies to exploit price trends.

- Application in Less Efficient Markets: Technical analysis may still be effective in markets with low liquidity or fewer informed participants, as these markets may not be fully weak form efficient. For example, in emerging markets or small-cap stocks, historical price data may reveal trends or patterns that technical analysis can exploit.

- Semi-Strong Form Efficiency and Technical Analysis

Semi-strong form efficiency posits that all publicly available information is reflected in prices, making both technical and fundamental analysis ineffective. If semi-strong efficiency holds, technical analysis would be unable to capitalize on new information or patterns because prices instantly adjust. However:- Short-Term Opportunities: Even in semi-strong efficient markets, some analysts find that short-term inefficiencies exist around high-impact events, such as earnings releases or economic data announcements. Technical traders may attempt to capture rapid price movements in the moments immediately following news releases, although this is challenging in highly liquid markets.

- Contrarian and Momentum Strategies: Some technical strategies, like contrarian (buying after sharp declines) and momentum (buying stocks with recent high performance), attempt to capitalize on overreaction and underreaction to news. These strategies assume that semi-strong efficiency doesn’t fully hold, allowing prices to drift over time, which technical traders can exploit.

- Strong Form Efficiency and Technical Analysis

Strong form efficiency, which suggests that all information—public and private—is fully priced in, implies that technical analysis would be entirely ineffective, as all data would already be reflected in asset prices. However, in reality, few markets are truly strong form efficient due to the influence of private, insider information. Consequently, strong form efficiency is not generally accepted for most financial markets, leaving room for technical analysis to uncover inefficiencies in certain cases.

Examples

Example 1: Stock Price Reaction to Earnings Announcement (Semi-Strong Form)

Suppose a major tech company announces its quarterly earnings, revealing higher-than-expected profits. In a semi-strong efficient market, the stock price would adjust almost instantly to reflect this new information. As soon as the announcement is made, buyers and sellers incorporate this data into their decisions, causing the price to rise quickly. Investors using fundamental analysis would not have an advantage, as the market has already factored in the earnings surprise. Thus, opportunities for “beating the market” through new public information would be limited.

Example 2: No Benefit from Technical Analysis (Weak Form)

An investor studies the historical price patterns and volume data of a popular stock, attempting to predict future movements using technical analysis tools like moving averages, support and resistance levels, or trend lines. In a weak-form efficient market, this strategy would not be effective, as all past price and volume information is already reflected in the current stock price. According to EMH, future price changes are independent of past patterns, and the stock follows a “random walk.” Thus, the investor’s efforts to gain an edge through historical data would be futile in a weak-form efficient market.

Example 3: Arbitrage Opportunities (Strong Form)

Imagine two identical financial products trading on different exchanges, with a slight price difference between them. An arbitrageur notices this discrepancy and buys the product at the lower price on one exchange while selling it at the higher price on another. In a strong-form efficient market, such arbitrage opportunities should not exist, as all available information, including insider and private knowledge, would be fully reflected in asset prices across exchanges. However, since real markets rarely achieve strong-form efficiency, arbitrage opportunities do occasionally arise, allowing savvy traders to profit from brief price disparities.

Example 4: Index Fund Popularity (Supporting EMH)

Index funds are a popular investment vehicle because they passively track the performance of a market index, like the S&P 500, rather than attempting to outperform it. In an efficient market, consistently outperforming the index is challenging, as all available information is already priced in. EMH suggests that active managers cannot regularly achieve above-average returns, especially after accounting for fees. This belief has driven many investors toward index funds, which align with EMH by aiming to capture market returns without attempting to beat them, thus supporting the theory that market prices reflect all available information.

Example 5: The January Effect (Contradicting EMH)

The “January Effect” is a market anomaly observed when stocks, especially small-cap stocks, tend to perform better in January than in other months. This pattern challenges EMH because it implies that predictable, calendar-based price movements can occur. Some investors may buy stocks in December, anticipating the January Effect, and then sell after the prices rise in January. In an efficient market, such seasonal patterns would be arbitraged away as investors act on them, but the persistent occurrence of the January Effect suggests that the market may not always be fully efficient, providing a challenge to EMH

Practice Questions

Question 1

What does the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) suggest about the availability of information and stock prices?

A. Stock prices do not reflect any available information

B. Stock prices reflect all available information instantly

C. Only insider information is reflected in stock prices

D. Stock prices only reflect past price trends

Answer: B. Stock prices reflect all available information instantly

Explanation: The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) posits that in an efficient market, stock prices instantly incorporate and reflect all available information. This means that any new public information is quickly absorbed into prices, making it difficult to achieve consistent, above-average returns based on that information. Therefore, EMH implies that it is nearly impossible to “beat the market” by using public information, as prices have already adjusted to it.

Question 2

According to the semi-strong form of the Efficient Market Hypothesis, which type of analysis is considered ineffective?

A. Technical analysis

B. Fundamental analysis

C. Both technical and fundamental analysis

D. Insider information analysis

Answer: C. Both technical and fundamental analysis

Explanation: The semi-strong form of EMH states that all publicly available information is already reflected in stock prices. This includes both historical data (used in technical analysis) and all public information (used in fundamental analysis). Therefore, according to the semi-strong form, both technical and fundamental analysis should be ineffective, as any publicly available information is already incorporated into the current stock price.

Question 3

Which of the following statements would contradict the EMF?

A. Stock prices follow a random walk and cannot be predicted

B. Market prices reflect all available information

C. Certain investors consistently earn higher returns through technical analysis

D. Insider information is not reflected in stock prices

Answer: C. Certain investors consistently earn higher returns through technical analysis

Explanation: The EMF suggests that it is impossible to consistently earn higher returns by using either technical or fundamental analysis because all available information is already reflected in stock prices. If certain investors consistently earn higher returns through technical analysis, it would contradict the EMH, as this would imply that past price information could predict future prices, which EMH argues is not possible.