99+ Oxymoron in Literature Examples

Discover the fascinating world of oxymorons in literature! This comprehensive guide unpacks the how, what, and why of using oxymorons to elevate your storytelling. Dive into gripping examples, practical writing tips, and everything you need to master this figure of speech.

What is Oxymoron in Literature? – Definition

An oxymoron in literature is a figure of speech where two contradictory terms are combined to create a meaningful expression. This stylistic device adds depth and intrigue to characters, settings, and plots, enriching the overall narrative. For a deeper understanding of how oxymorons function as a figure of speech, our article on oxymorons as a figure of speech offers valuable insights.

What is the best Example of an Oxymoron in Literature?

One of the most iconic examples of an oxymoron in literature comes from Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet” where the phrase “parting is such sweet sorrow” is used. Here, “sweet” and “sorrow” are contradictory terms, yet when combined, they perfectly capture the complex emotions felt during a farewell. This oxymoron adds a layer of depth to the situation, making it one of the most cited instances of this literary device. For those intrigued by the use of oxymorons in poetic forms, our oxymorons in poetry article provides a wealth of examples.

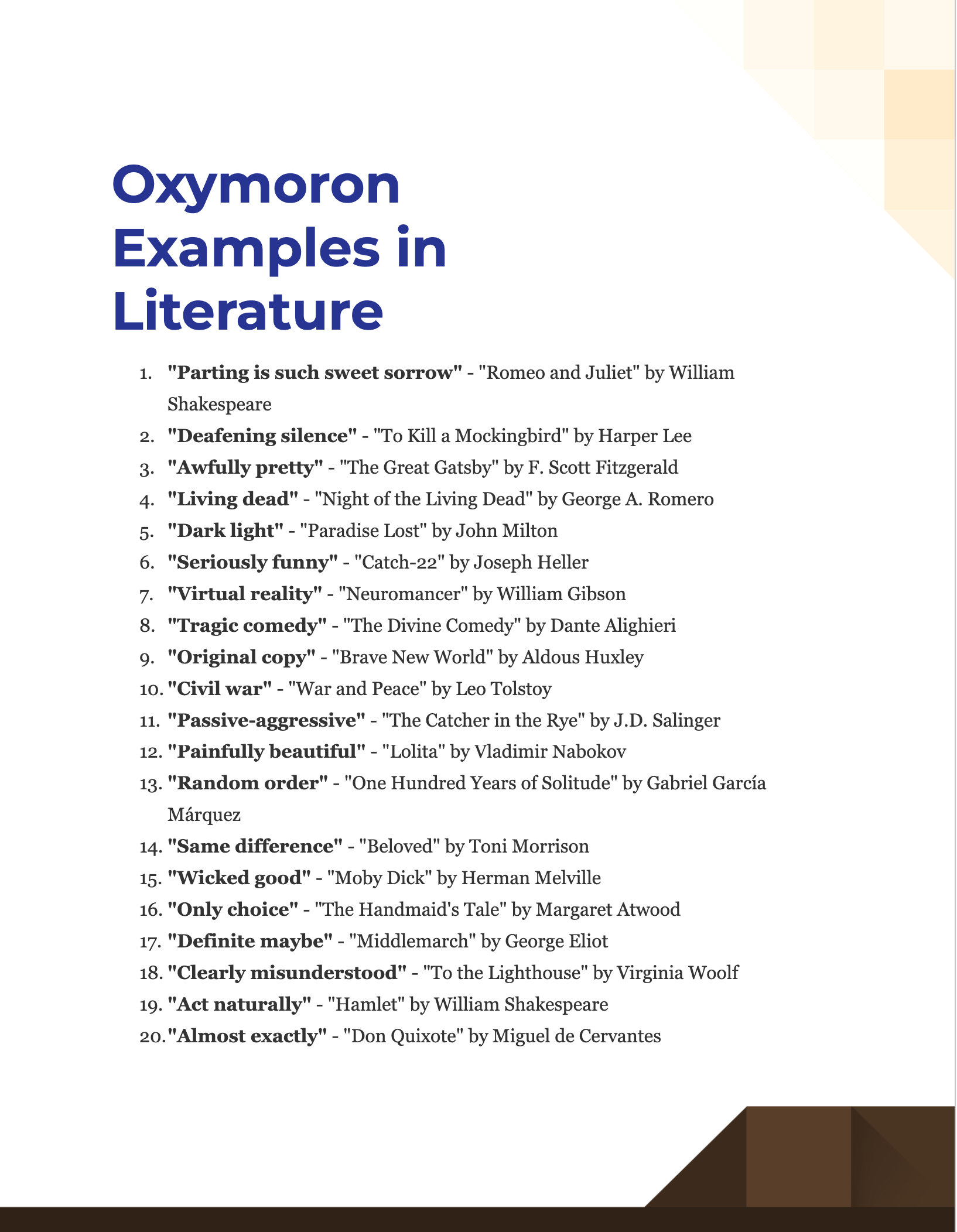

100 Oxymoron in Literature Examples

Unearth the literary goldmine of oxymorons in books, plays, and poems. With the power to surprise, delight, and challenge your perceptions, oxymorons have been the favorite tool of many renowned authors. Let’s delve into 100 compelling examples, each finely crafted to resonate with readers and enrich narratives. For a lighter take on oxymorons, our funny oxymorons article offers a collection that’s sure to bring a smile to your face.

- “Parting is such sweet sorrow” – “Romeo and Juliet” by William Shakespeare

- “Deafening silence” – “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee

- “Awfully pretty” – “The Great Gatsby” by F. Scott Fitzgerald

- “Living dead” – “Night of the Living Dead” by George A. Romero

- “Dark light” – “Paradise Lost” by John Milton

- “Seriously funny” – “Catch-22” by Joseph Heller

- “Virtual reality” – “Neuromancer” by William Gibson

- “Tragic comedy” – “The Divine Comedy” by Dante Alighieri

- “Original copy” – “Brave New World” by Aldous Huxley

- “Civil war” – “War and Peace” by Leo Tolstoy

- “Passive-aggressive” – “The Catcher in the Rye” by J.D. Salinger

- “Painfully beautiful” – “Lolita” by Vladimir Nabokov

- “Random order” – “One Hundred Years of Solitude” by Gabriel García Márquez

- “Same difference” – “Beloved” by Toni Morrison

- “Wicked good” – “Moby Dick” by Herman Melville

- “Only choice” – “The Handmaid’s Tale” by Margaret Atwood

- “Definite maybe” – “Middlemarch” by George Eliot

- “Clearly misunderstood” – “To the Lighthouse” by Virginia Woolf

- “Act naturally” – “Hamlet” by William Shakespeare

- “Almost exactly” – “Don Quixote” by Miguel de Cervantes

- “Old news” – “1984” by George Orwell

- “Seriously joking” – “Pride and Prejudice” by Jane Austen

- “Larger half” – “Infinite Jest” by David Foster Wallace

- “Awful good” – “The Grapes of Wrath” by John Steinbeck

- “Terribly pleased” – “Emma” by Jane Austen

- “Small crowd” – “The Sun Also Rises” by Ernest Hemingway

- “Passive resistance” – “Civil Disobedience” by Henry David Thoreau

- “Exact estimate” – “Ulysses” by James Joyce

- “Genuine imitation” – “Breakfast of Champions” by Kurt Vonnegut

- “False truth” – “The Da Vinci Code” by Dan Brown

- “Pretty ugly” – “The Picture of Dorian Gray” by Oscar Wilde

- “Known secret” – “The Secret” by Rhonda Byrne

- “Jumbo shrimp” – “Moby Dick” by Herman Melville

- “Open secret” – “The Spy Who Came in from the Cold” by John le Carré

- “Growing smaller” – “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” by Lewis Carroll

- “Acting naturally” – “As You Like It” by William Shakespeare

- “Freezing hot” – “Fahrenheit 451” by Ray Bradbury

- “Same difference” – “The Fault in Our Stars” by John Green

- “Quiet Riot” – “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” by Robert Louis Stevenson

- “Alone together” – “One Hundred Years of Solitude” by Gabriel García Márquez

- “Painfully beautiful” – “Lolita” by Vladimir Nabokov

- “Random order” – “The Catcher in the Rye” by J.D. Salinger

- “Clearly misunderstood” – “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee

- “Living dead” – “Dracula” by Bram Stoker

- “Virtual reality” – “Neuromancer” by William Gibson

- “Original copy” – “Don Quixote” by Miguel de Cervantes

- “Liquid gas” – “Brave New World” by Aldous Huxley

- “Deafening silence” – “Slaughterhouse-Five” by Kurt Vonnegut

- “Negative growth” – “The Road” by Cormac McCarthy

- “Bittersweet symphony” – “War and Peace” by Leo Tolstoy

- “Passive-aggressive” – “Lord of the Flies” by William Golding

- “Clearly confused” – “The Bell Jar” by Sylvia Plath

- “Awfully pretty” – “Great Expectations” by Charles Dickens

- “Tragic comedy” – “Catch-22” by Joseph Heller

- “Seriously funny” – “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy” by Douglas Adams

- “Passive confrontation” – “Wuthering Heights” by Emily Brontë

- “Sad joy” – “Les Misérables” by Victor Hugo

- “Friendly fire” – “The Things They Carried” by Tim O’Brien

- “Awful beauty” – “The Waste Land” by T.S. Eliot

- “Wicked good” – “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone” by J.K. Rowling

- “Irregular pattern” – “Gulliver’s Travels” by Jonathan Swift

- “Minor crisis” – “Anna Karenina” by Leo Tolstoy

- “Seriously casual” – “The Importance of Being Earnest” by Oscar Wilde

- “Busy doing nothing” – “Winnie the Pooh” by A.A. Milne

- “Small giant” – “David Copperfield” by Charles Dickens

- “Famously unknown” – “The Invisible Man” by H.G. Wells

- “Numb feeling” – “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” by Ken Kesey

- “Old news” – “The Scarlet Letter” by Nathaniel Hawthorne

- “Anxious patience” – “Sense and Sensibility” by Jane Austen

- “Passive action” – “The Odyssey” by Homer

- “Virtual fact” – “Dune” by Frank Herbert

- “Simple complexity” – “Mere Christianity” by C.S. Lewis

- “Dark light” – “Paradise Lost” by John Milton

- “Joyful tears” – “Pride and Prejudice” by Jane Austen

- “Dry rain” – “The Grapes of Wrath” by John Steinbeck

- “Empty fullness” – “To the Lighthouse” by Virginia Woolf

- “Quiet storm” – “The Tempest” by William Shakespeare

- “Bad luck” – “Of Mice and Men” by John Steinbeck

- “Fictional reality” – “Life of Pi” by Yann Martel

- “Unbiased opinion” – “The Jungle” by Upton Sinclair

- “Deafening quiet” – “The Sound and the Fury” by William Faulkner

- “Alone together” – “Steppenwolf” by Hermann Hesse

- “Honest thief” – “Oliver Twist” by Charles Dickens

- “Open secret” – “The Secret Garden” by Frances Hodgson Burnett

- “Tragic optimism” – “Man’s Search for Meaning” by Viktor Frankl

- “Idle industry” – “The Wealth of Nations” by Adam Smith

- “Painful relief” – “Beloved” by Toni Morrison

- “Minor miracle” – “The Alchemist” by Paulo Coelho

- “Simple paradox” – “A Tale of Two Cities” by Charles Dickens

- “Fading sparkle” – “The Great Gatsby” by F. Scott Fitzgerald

- “Living fossil” – “Jurassic Park” by Michael Crichton

- “Detailed summary” – “Inferno” by Dante Alighieri

- “Unseen observation” – “1984” by George Orwell

- “Mournful celebration” – “Their Eyes Were Watching God” by Zora Neale Hurston

- “Bound freedom” – “The Handmaid’s Tale” by Margaret Atwood

- “Rough smoothness” – “Moby-Dick” by Herman Melville

- “Passive intensity” – “The Picture of Dorian Gray” by Oscar Wilde

- “Frozen fire” – “Fahrenheit 451” by Ray Bradbury

- “Humorous tragedy” – “The Book Thief” by Markus Zusak

- “Awkward grace” – “Ballet Shoes” by Noel Streatfeild

Oxymoron in Literature Examples in Poetry

In the realm of poetic expression, oxymorons create an intriguing interplay of conflicting ideas, enriching the lyrical landscape. Often used for vivid imagery, heightened emotion, and dramatic contrast, oxymorons in poetry are tools that poets wield for impact and resonance. Here are 10 distinct examples.

- “Parting is such sweet sorrow” – “Romeo and Juliet” by William Shakespeare

- “Innocent Guilt” – “Paradise Lost” by John Milton

- “Darkness visible” – “Paradise Lost” by John Milton

- “Bitter sweet” – “Ode on Melancholy” by John Keats

- “Still waking sleep” – “Sonnet 43” by William Shakespeare

- “Awful good” – “Mending Wall” by Robert Frost

- “Jumbo shrimp” – “The Waste Land” by T.S. Eliot

- “Clearly confused” – “Ariel” by Sylvia Plath

- “Foolish wisdom” – “Leaves of Grass” by Walt Whitman

- “Dull roar” – “Howl” by Allen Ginsberg

Oral Oxymoron in Literature Examples

Oral literature has its own wealth of oxymorons, often presented to add flavor to spoken narratives or dialogues. From folk tales to contemporary spoken word, the oxymoron serves to captivate the audience while underscoring paradoxical truths. Dive into these 10 examples.

- “Jumbo shrimp” – Mark Twain’s Speeches

- “Same difference” – “The Canterbury Tales” by Geoffrey Chaucer

- “Old news” – “Huckleberry Finn” by Mark Twain

- “Terrible beauty” – Winston Churchill’s Speeches

- “Virtual reality” – “Neuromancer” by William Gibson

- “Definitely maybe” – “On the Road” by Jack Kerouac

- “Pretty ugly” – “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee

- “Random order” – “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” by Hunter S. Thompson

- “Awfully nice” – “Pride and Prejudice” by Jane Austen

- “Small crowd” – “The Catcher in the Rye” by J.D. Salinger

Importance of Oxymoron in Literature

The use of oxymorons in literature serves as a versatile technique to convey a multitude of emotions, paradoxes, and complexities. This figure of speech can dramatize a conflict, deepen the meaning of a situation, or add humor. Oxymorons often elevate the reader’s interest, adding a layer of richness and intricacy. They can provoke thought, encapsulate irony, and create tension, making them an invaluable asset for literary impact. For a deeper dive into the emotional aspects of oxymorons, our emotional oxymorons article is a must-read.

How Do You Write an Oxymoron in Literature? – Step by Step Guide

Crafting an oxymoron in literature requires a blend of creativity, contextual understanding, and linguistic flair. The process involves identifying the context, brainstorming contrasting ideas, evaluating impact, and inserting the oxymoron into the text. For those looking to introduce younger readers to this literary device, our oxymorons for kids article offers a step-by-step guide that simplifies the process.

- Identify the Context: Know where the oxymoron will fit in your narrative, dialogue, or verse.

- Brainstorm Contrasting Ideas: Think of words that hold opposite meanings but could be combined to create a layered or ironic truth.

- Evaluate the Impact: Ensure that your chosen oxymoron adds value—whether emotional, intellectual, or humorous—to the surrounding text.

- Insert into Text: Place the oxymoron where it enhances the tone or meaning.

- Read Aloud: Say the sentence or phrase aloud to test if it sounds natural and achieves the desired impact.

- Revise if Needed: If the oxymoron feels forced or ineffective, consider modifications or even removal.

- Seek Feedback: Sometimes it helps to get a second opinion to ensure your oxymoron achieves its intended purpose.

Tips for Using Oxymoron in Literature

- Be Context-Aware: An oxymoron will only be effective if it suits the context and serves a clear purpose within the larger piece.

- Avoid Overuse: Oxymorons are impactful in moderation but can become gimmicky if overused.

- Strive for Originality: Commonly used oxymorons like ‘deafening silence’ can be less impactful. Try to create something unique.

- Maintain Subtlety: The best oxymorons are those that blend seamlessly into the text, adding depth without drawing attention away from the narrative.

- Test Multiple Options: Sometimes the first oxymoron that comes to mind may not be the best fit. Don’t hesitate to try different combinations to find what works best.

- Edit Carefully: In your revision process, make sure the oxymoron still holds its weight and relevance.

- Read Widely: The more you read, the more you’ll encounter oxymorons that are masterfully used, providing inspiration for your own work.

Oxymorons can add a dash of zest to literary works, making them more engaging, emotionally resonant, and thought-provoking. For those interested in exploring more types of oxymorons, our articles on comical oxymorons and paradoxical oxymorons offer additional perspectives.