In civil procedure, jurisdiction and venue are foundational concepts that determine where and how legal cases are heard. Jurisdiction refers to a court's authority to hear a case, encompassing both subject matter jurisdiction (the court’s ability to hear a type of case) and personal jurisdiction (authority over the parties involved). Venue, on the other hand, designates the appropriate geographic location for the trial. Understanding jurisdiction and venue ensures that cases are filed in courts with proper authority and in locations that promote fairness and convenience for all parties involved.

Learning Objectives

In studying "Jurisdiction and Venue" for the MBE, you should learn to understand the foundational principles governing federal and state court jurisdiction, including subject matter, personal jurisdiction, and venue requirements. Evaluate how courts establish jurisdiction over parties and cases, focusing on concepts like minimum contacts, purposeful availment, and diversity jurisdiction. Examine the procedures for removal from state to federal court and the limitations on such actions. Additionally, understand how improper venue and jurisdictional challenges are raised and resolved. Apply this knowledge to analyze fact patterns and identify appropriate jurisdictional and venue rulings in practice questions and exam scenarios.

1. Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction is the legal authority of a court to hear and decide a particular case, encompassing both the power to make a judgment and to enforce it. Jurisdiction is essential in determining where a case can be filed and which court can lawfully resolve the dispute.

Types of Jurisdiction

Subject Matter Jurisdiction : The power of a court to hear cases of a particular type or those that involve specific subject matter. This authority ensures that cases are brought before a court that has the expertise or designated authority over the issue.

Federal Question Jurisdiction: Arises when a case involves a question of federal law, such as issues related to the U.S. Constitution, federal statutes, or treaties.

Diversity Jurisdiction: Allows federal courts to hear cases where the parties are from different states (or a foreign country) and the amount in controversy exceeds $75,000.

Complete Diversity Rule: All plaintiffs must be from different states than all defendants for diversity jurisdiction.

Supplemental Jurisdiction: Allows a federal court to hear additional state claims that are closely related to the federal issues being litigated.

Exclusive vs. Concurrent Jurisdiction: Certain cases, such as bankruptcy, are exclusively federal, while others, like personal injury, can be heard in either state or federal court.

Personal Jurisdiction : The court’s authority over the parties involved in the lawsuit, particularly the defendant. For personal jurisdiction to be valid, the defendant must have certain minimum contacts with the state to ensure fairness.

Traditional Bases: Personal jurisdiction is traditionally established by domicile, presence in the forum state when served, or consent.

Long-Arm Statutes: States can exercise jurisdiction over non-resident defendants if they have sufficient contacts with the state.

Minimum Contacts Test: The defendant must have sufficient contacts with the forum state such that requiring them to appear is fair and just.

Purposeful Availment: The defendant must have purposefully availed themselves of the benefits and protections of the forum state.

Reasonableness and Fairness Factors: Courts consider the burden on the defendant, the state’s interest, and the plaintiff’s interest in obtaining relief.

In Rem and Quasi In Rem Jurisdiction: These involve jurisdiction over property located within the court’s territory rather than over persons.

2. Venue

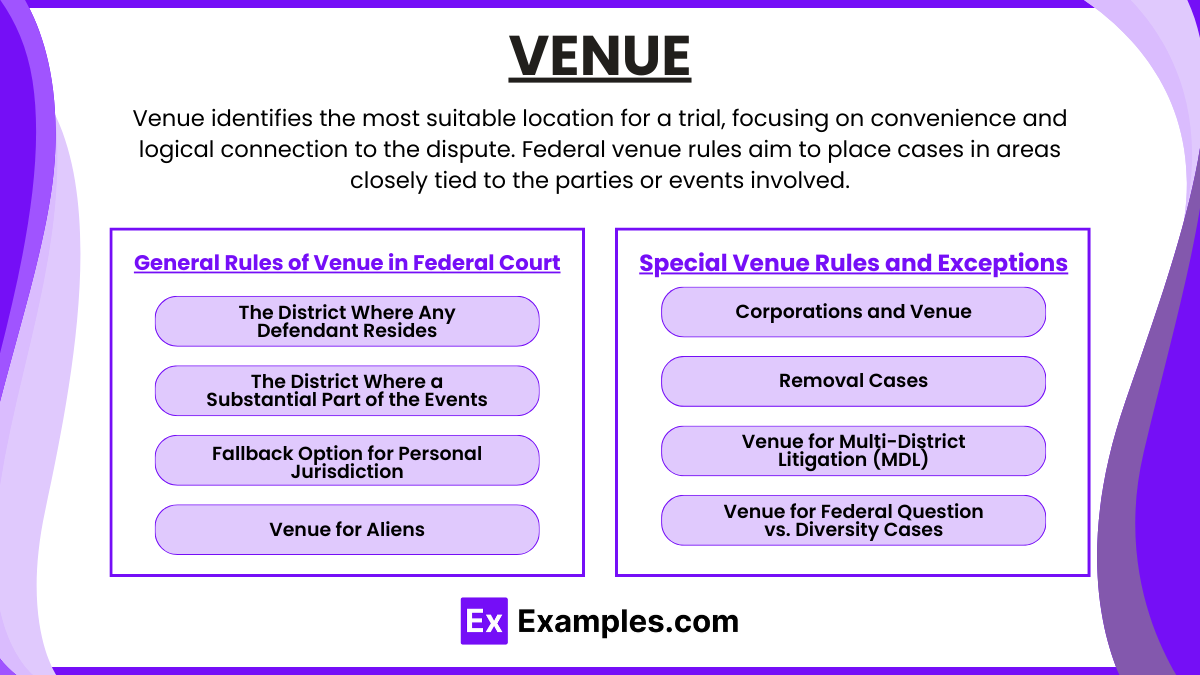

Venue determines the most appropriate and convenient location within the judicial system to hold a trial, addressing practical concerns about where a lawsuit should proceed. Federal venue rules are designed to ensure that cases are tried in locations that have a logical connection to the dispute or where the parties reside.

General Rules of Venue in Federal Court:

Under 28 U.S.C. § 1391, venue is proper in:

The District Where Any Defendant Resides: If all defendants reside in the same state, the plaintiff can file suit in any district within that state where at least one defendant resides.

The District Where a Substantial Part of the Events: Venue is appropriate in a district where a significant portion of the actions giving rise to the claim took place, such as the place of injury, contract execution, or property in dispute.

Fallback Option for Personal Jurisdiction: If there is no district in which the case may otherwise be brought, venue is proper in any district where at least one defendant is subject to personal jurisdiction.

Venue for Aliens: Under 28 U.S.C. § 1391(c)(3), an alien (a defendant who is not a U.S. citizen or permanent resident) may be sued in any judicial district. This rule provides flexibility for plaintiffs when suing foreign defendants, as it eliminates venue restrictions based on the defendant’s residence, allowing the case to be filed in any federal district with proper jurisdiction.

Special Venue Rules and Exceptions:

Certain categories of cases and parties have specific venue rules, often due to the nature of the party (like corporations) or the action (such as removal from state to federal court).

Corporations and Venue:

A corporation can “reside” in multiple districts within a state if it has sufficient contacts to establish personal jurisdiction within those areas.

If a state has multiple judicial districts, a corporation resides in any district where it would be subject to personal jurisdiction as if that district were a separate state. If the corporation has significant contacts statewide, it may be subject to venue in multiple districts within the state.

Removal Cases:

In cases removed from state to federal court, venue is automatically appropriate in the federal district that encompasses the location where the state action was initially filed.

This prevents “forum shopping” upon removal by setting the federal venue as the district corresponding to the original state court.

Venue for Multi-District Litigation (MDL):

In cases involving complex litigation, like mass torts, cases may be consolidated into a single district to streamline pretrial proceedings. The Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation determines the MDL venue, considering factors like efficiency and convenience for all parties.

Venue for Federal Question vs. Diversity Cases:

Venue in federal question cases often centers on the location where the events took place or where defendants reside.

In diversity cases, venue rules serve to ensure fairness to parties from different states, maintaining neutrality by grounding venue in relevant connections to the dispute.

3. Removal Jurisdiction

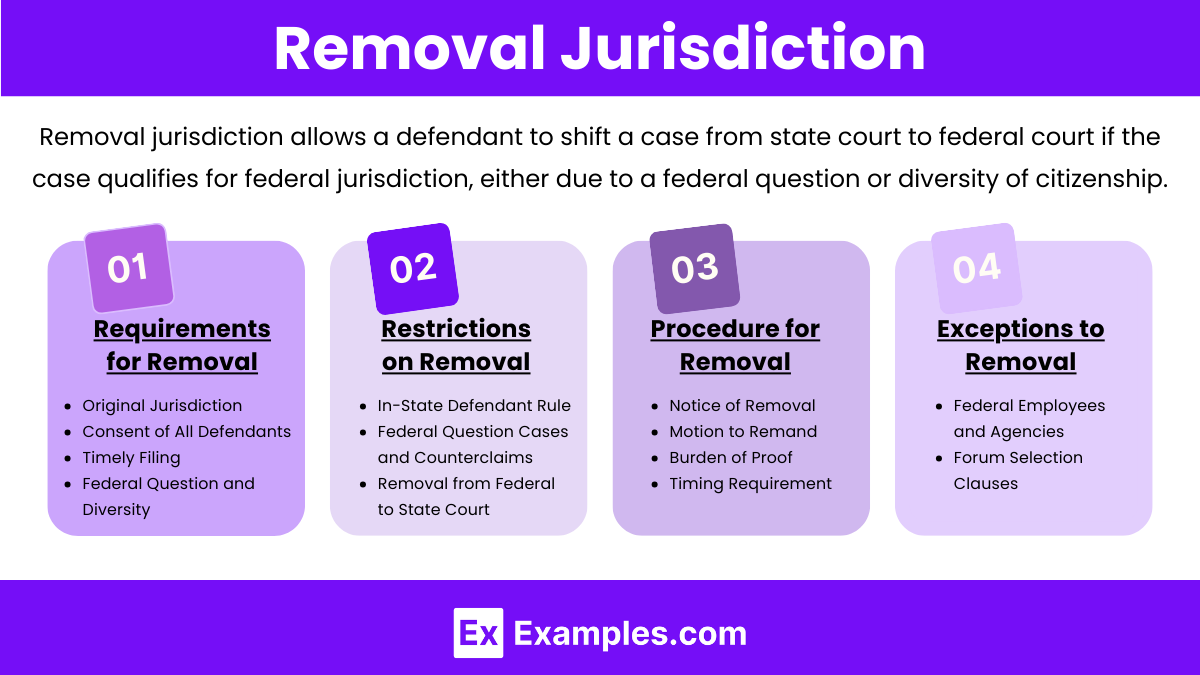

Removal jurisdiction allows a defendant to shift a case from state court to federal court if the case qualifies for federal jurisdiction, either due to a federal question or diversity of citizenship.

Requirements for Removal:

Original Jurisdiction: The case must have been eligible for federal jurisdiction from the outset, meaning it could have initially been filed in federal court.

Consent of All Defendants: All defendants in the case must consent to removal. This requirement prevents partial removal and ensures consistency among co-defendants.

Timely Filing: The notice of removal must be filed within 30 days after the defendant receives the initial complaint or pleading. If the case becomes removable at a later date (e.g., if a non-diverse party is dismissed), the 30-day period starts anew from that point.

Federal Question and Diversity: For federal question cases, removal is generally straightforward if the plaintiff's claim arises under federal law. For diversity cases, complete diversity must exist, and the amount in controversy must exceed $75,000.

Restrictions on Removal:

In-State Defendant Rule (Home-State Rule): In diversity cases, removal is prohibited if any defendant is a citizen of the state in which the action was filed (28 U.S.C. § 1441(b)(2)). This rule prevents defendants from using federal courts as an escape from a local plaintiff’s court.

Federal Question Cases and Counterclaims: Cases cannot be removed based on federal question jurisdiction if the federal issue arises only as a defense or counterclaim by the defendant. Federal question jurisdiction must be clear in the plaintiff's initial complaint.

Removal from Federal to State Court: There is no provision for removing a case from federal to state court. If a federal court lacks jurisdiction after removal, it must remand the case back to state court.

Procedure for Removal:

Notice of Removal: To initiate removal, the defendant must file a "Notice of Removal" in federal court and notify both the plaintiff and the state court. The notice must contain all grounds for removal and any supporting documentation.

Motion to Remand: Plaintiffs who oppose removal can file a motion to remand the case back to state court. Common grounds for remand include procedural defects in the removal or lack of subject matter jurisdiction.

Burden of Proof: The burden of establishing federal jurisdiction lies with the defendant seeking removal. If challenged, the defendant must demonstrate that the case meets federal jurisdiction requirements.

Timing Requirement: The defendant must file the Notice of Removal within 30 days of receiving the initial complaint or amended pleading that first allows for removal.

Exceptions to Removal:

Federal Employees and Agencies: Certain cases involving federal employees or agencies may have special removal rights under statutes like the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA) or the Westfall Act.

Forum Selection Clauses: If a contract includes a forum selection clause specifying a state court, this may limit a defendant’s ability to remove the case to federal court, depending on how the clause is interpreted.

4. Jurisdictional Challenges and Waivers

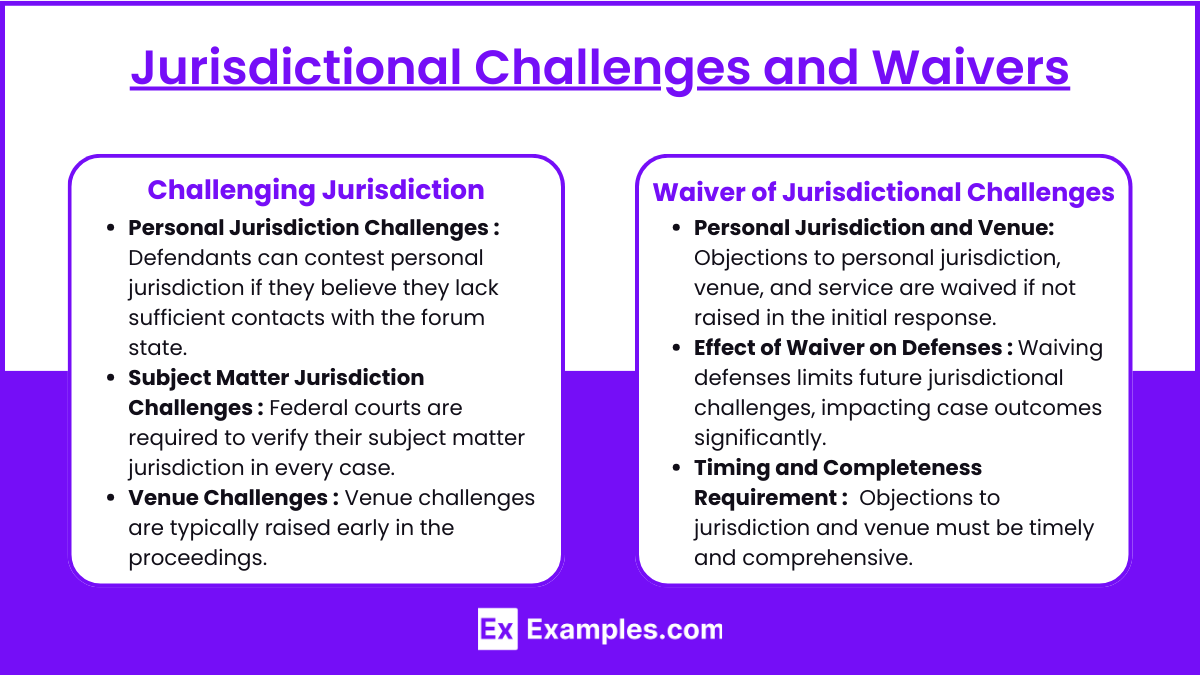

Challenging Jurisdiction:

Personal Jurisdiction Challenges: Defendants can contest personal jurisdiction if they believe they lack sufficient contacts with the forum state. Challenges can be made by a motion to dismiss under Rule 12(b)(2).

Subject Matter Jurisdiction Challenges: Federal courts are required to verify their subject matter jurisdiction in every case. Defendants (or plaintiffs) can challenge subject matter jurisdiction at any time, even on appeal, because it cannot be waived.

Venue Challenges: Venue challenges are typically raised early in the proceedings. If the venue is improper, defendants can move for dismissal or request a transfer to a more suitable venue under 28 U.S.C. § 1406(a) or § 1404(a).

Waiver of Jurisdictional Challenges:

Personal Jurisdiction and Venue: Under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(h), objections to personal jurisdiction, improper venue, and insufficient service of process are waived if not raised in the first responsive pleading or motion (Rule 12(b) motion).

Effect of Waiver on Defenses: Failing to assert certain defenses, like personal jurisdiction, can permanently bar the defendant from contesting jurisdiction later in the case, which can affect the outcome of the case significantly.

Timing and Completeness Requirement: Under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, objections related to jurisdiction and venue must not only be raised in the first responsive pleading or motion, but they must also be complete.

Examples

Example 1: Diversity Jurisdiction and Venue

A Florida citizen sues a Texas corporation in federal court for breach of contract, claiming damages of $100,000. The corporation is incorporated in Delaware but has its principal place of business in Texas. The lawsuit is filed in a federal district court in Florida.

Analysis: This case satisfies diversity jurisdiction because there is complete diversity (the plaintiff is a Florida resident, and the defendant corporation is considered a resident of Texas and Delaware, not Florida) and the amount in controversy exceeds $75,000. However, the defendant may challenge venue, arguing that Texas is the appropriate location, as it is the corporation's principal place of business, and a significant portion of the business activities related to the contract occurred there.

Example 2: Federal Question Jurisdiction and Removal

A California resident sues a New York company in California state court, alleging patent infringement under federal law. The defendant wishes to remove the case to federal court.

Analysis: Since patent infringement is a federal question under 28 U.S.C. § 1331, the defendant can remove the case to federal court. Under the removal statute, the case is eligible for removal to a federal district court that encompasses the area where the state court is located. The defendant must file a notice of removal within 30 days of being served with the complaint. Once removed, the case will proceed under federal law due to the federal question jurisdiction.

Example 3: Minimum Contacts and Personal Jurisdiction

A New Jersey company sues an Illinois resident in New Jersey for breach of contract. The Illinois resident visited New Jersey once to negotiate the contract but has no other ties to the state. The defendant argues that New Jersey lacks personal jurisdiction.

Analysis: Under the "minimum contacts" test, New Jersey might assert personal jurisdiction over the Illinois resident if the court finds that their visit to New Jersey to negotiate the contract constitutes sufficient contact related to the lawsuit. However, if the contract’s performance occurred entirely outside of New Jersey, or if the court deems the single visit insufficient for "purposeful availment," the defendant’s challenge to personal jurisdiction may succeed.

Example 4: Forum Non Conveniens

A Canadian citizen files a wrongful death suit in federal court in California against a California-based airline after a plane crash in Canada. Most witnesses and evidence are located in Canada, and Canadian law will likely govern the case.

Analysis: The defendant may request dismissal based on the doctrine of forum non conveniens, arguing that Canadian courts provide a more suitable forum for the litigation due to the location of witnesses, evidence, and the applicability of Canadian law. If the court agrees that Canada is an adequate alternative forum and the case would be more appropriately heard there, it may dismiss the suit, even though personal and subject matter jurisdiction are technically satisfied in California.

Example 5: Removal Restrictions in Diversity Jurisdiction

A citizen of Georgia files a lawsuit in Georgia state court against two defendants, one from Alabama and one from Georgia, claiming $80,000 in damages. The Alabama defendant wishes to remove the case to federal court based on diversity jurisdiction.

Analysis: Although there is diversity of citizenship between the plaintiff and the Alabama defendant, complete diversity is not met because one of the defendants is also a Georgia resident. Additionally, because one of the defendants is a citizen of the state where the action is brought, removal is barred under the "home-state defendant rule." Therefore, the Alabama defendant cannot remove the case to federal court.

Practice Questions

Question 1

Plaintiff, a resident of State A, files a lawsuit in State A’s federal district court against Defendant, a resident of State B, claiming $50,000 in damages for breach of contract. Defendant moves to dismiss for lack of subject matter jurisdiction. How should the court rule?

A. Grant the motion because the amount in controversy does not exceed $75,000.

B. Grant the motion because there is no diversity of citizenship.

C. Deny the motion because federal courts always have jurisdiction over contract disputes.

D. Deny the motion because the parties are from different states.

Answer: A. Grant the motion because the amount in controversy does not exceed $75,000.

Explanation: For federal courts to have diversity jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 1332, two requirements must be met:

Complete Diversity of Citizenship: All plaintiffs must be citizens of different states than all defendants. Here, Plaintiff and Defendant are from different states, so this requirement is satisfied.

Amount in Controversy: The amount in controversy must exceed $75,000. In this case, Plaintiff claims only 50,000 dollars in damages, which does not meet the minimum threshold.

Since the amount in controversy requirement is not met, the federal court does not have subject matter jurisdiction, and the motion to dismiss for lack of subject matter jurisdiction should be granted. Options B, C, and D are incorrect because they do not correctly address the diversity and amount in controversy requirements.

Question 2

John, a resident of State X, sues Sarah, a resident of State Y, in State X’s state court for damages exceeding $100,000, alleging violation of a federal statute. Sarah would prefer to litigate in federal court. Can she remove the case to federal court?

A. Yes, because there is federal question jurisdiction.

B. Yes, because there is diversity jurisdiction.

C. No, because the amount in controversy is not sufficient for federal jurisdiction.

D. No, because removal is only available to the plaintiff.

Answer: A. Yes, because there is federal question jurisdiction.

Explanation: A defendant can remove a case from state court to federal court if the federal court would have had original jurisdiction over the case. In this case:

Federal Question Jurisdiction applies because the claim is based on a federal statute. Under 28 U.S.C. § 1331, cases arising under federal law are eligible for federal court jurisdiction.

Diversity Jurisdiction also appears to be satisfied because the parties are residents of different states, and the amount in controversy exceeds $75,000. However, since the case already has a federal question basis, this reason alone would suffice for removal.

Option C is incorrect because the amount in controversy requirement applies only to diversity jurisdiction and does not impact federal question jurisdiction. Option D is incorrect because only defendants have the right to remove cases to federal court; plaintiffs cannot remove cases they have filed in state court.

Question 3

Rachel, a resident of State A, sues Mike, a resident of State B, in State B's federal district court for a car accident that occurred in State A. Which of the following is true about the venue?

A. The venue is improper because Rachel should have filed in State A, where the accident occurred.

B. The venue is proper because Mike resides in State B.

C. The venue is improper because the case involves a resident of both State A and State B.

D. The venue is proper because the federal court always has jurisdiction over car accident cases.

Answer: B. The venue is proper because Mike resides in State B.

Explanation: Under 28 U.S.C. § 1391(b), venue in a federal case is generally proper in:

A judicial district where any defendant resides, if all defendants reside in the same state.

A district where a substantial part of the events or omissions giving rise to the claim occurred.

In this case, because Mike, the defendant, resides in State B, filing in State B’s federal district court is appropriate under the first rule. Option A is incorrect because although the accident occurred in State A, the plaintiff has the choice to file in the defendant's home district, which is State B. Option C is incorrect because the residency of each party does not make the venue improper. Option D is incorrect as federal courts do not always have jurisdiction over car accidents; jurisdiction depends on factors such as diversity of citizenship or federal question jurisdiction.