The "Law Applied by Federal Courts" explores the principles governing which laws federal courts apply in cases under their jurisdiction. In diversity cases, federal courts follow state substantive law while adhering to federal procedural rules, guided by the Erie Doctrine. In cases involving federal questions, they apply federal law directly. Key doctrines and tests, such as the outcome-determinative test and the Rules Enabling Act, help determine the appropriate application, balancing federal uniformity with respect for state law in a unified legal framework.

Learning Objectives

In studying "Law Applied by Federal Courts" for the MBE Exam, you should learn to understand the principles guiding federal courts in determining which laws to apply in cases involving diversity jurisdiction and federal question jurisdiction. Analyze doctrines like Erie, outcome-determinative tests, and the Rules Enabling Act (REA) to distinguish between substantive and procedural law. Evaluate landmark cases such as Erie Railroad Co. v. Tompkins, Hanna v. Plumer, and Guaranty Trust Co. v. York to understand how federal courts balance federal and state interests. Apply these concepts to interpret scenarios on law selection and jurisdictional boundaries in MBE practice questions.

1. Understanding Diversity Jurisdiction

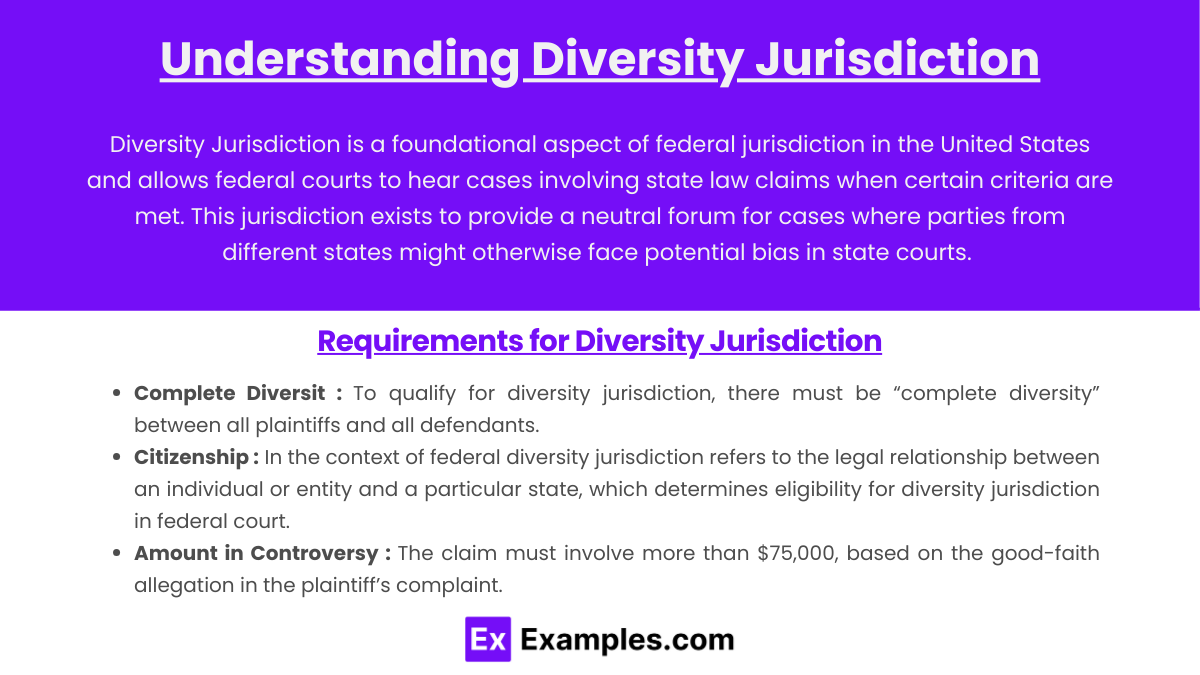

Diversity Jurisdiction is a foundational aspect of federal jurisdiction in the United States and allows federal courts to hear cases involving state law claims when certain criteria are met. This jurisdiction exists to provide a neutral forum for cases where parties from different states might otherwise face potential bias in state courts. Diversity jurisdiction refers to the power of federal courts to hear civil cases where the parties are from different states or countries, ensuring that no party has a "home court" advantage. Below is an in-depth explanation of diversity jurisdiction, including its requirements, key principles, and significant considerations.

Requirements for Diversity Jurisdiction

Complete Diversity: To qualify for diversity jurisdiction, there must be “complete diversity” between all plaintiffs and all defendants. This principle, established in Strawbridge v. Curtiss (1806), means that no plaintiff can be a citizen of the same state as any defendant.

Citizenship: Citizenship in the context of federal diversity jurisdiction refers to the legal relationship between an individual or entity and a particular state, which determines eligibility for diversity jurisdiction in federal court.

Individuals: A person’s citizenship is determined by their domicile, which is their permanent home or the place they intend to return to. Domicile is not necessarily the same as residence; it requires both physical presence and intent to remain indefinitely.

Corporations: A corporation is considered a citizen of both its state of incorporation and the state where it has its principal place of business (often defined as its “nerve center”).

Other Entities: Partnerships and LLCs take the citizenship of all their members, which can complicate diversity jurisdiction.

Amount in Controversy: The claim must involve more than 75,000 will the court dismiss for lack of jurisdiction.

2. Tests for Determining Substantive and Procedural Law

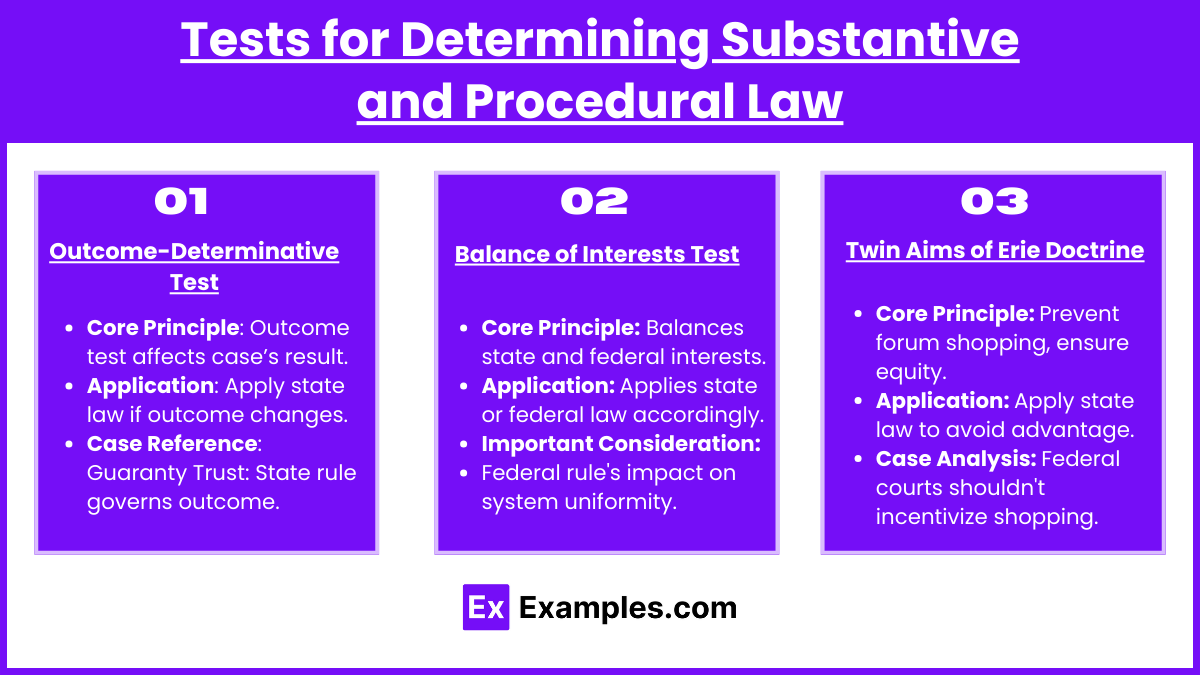

In federal courts, distinguishing between substantive and procedural law is pivotal for determining whether to apply state or federal law. The Supreme Court has developed several tests to address this, each with unique applications and nuances:

1. Outcome-Determinative Test

Core Principle: The outcome-determinative test assesses whether the choice between state and federal law will significantly affect the case’s outcome.

Application: If applying one rule instead of another (e.g., federal versus state) changes the outcome, state law should generally apply to avoid inequitable administration.

Case Reference: In Guaranty Trust Co. v. York (1945), the Supreme Court applied this test to determine that state law (specifically, a state statute of limitations) should govern when applying a federal rule would lead to a different outcome, as it was crucial to equitable treatment between state and federal cases.

2. Balance of Interests Test

Core Principle: Originating from Byrd v. Blue Ridge Rural Electric Cooperative, Inc. (1958), this test compares the interests of the state and federal systems.

Application: If the state’s interest in applying its law outweighs federal interests, the court will apply state law, and vice versa. This test allows for flexibility, especially in cases where the federal government’s procedural practices are essential for uniformity or where the state's interest is particularly compelling.

Important Consideration: Courts applying this test must evaluate if the federal procedural rule is essential to the functioning of the federal system and the balance of rights within that system, even if it may lead to a different outcome than state law would.

3. Twin Aims of Erie Doctrine

Core Principle: The twin aims of Erie, as clarified in Hanna v. Plumer (1965), are to (1) prevent forum shopping and (2) ensure the equitable administration of laws.

Application: If applying a federal rule would encourage parties to choose federal court over state court to gain a favorable procedural or substantive advantage, then the state law should apply. This approach aligns with Erie’s objective to create parity between state and federal courts.

Case Analysis: In Hanna, the Supreme Court also highlighted that the federal courts should not create incentives for forum shopping, which could disrupt the balance between state and federal courts.

3. Federal Rules of Civil Procedure vs. State Law

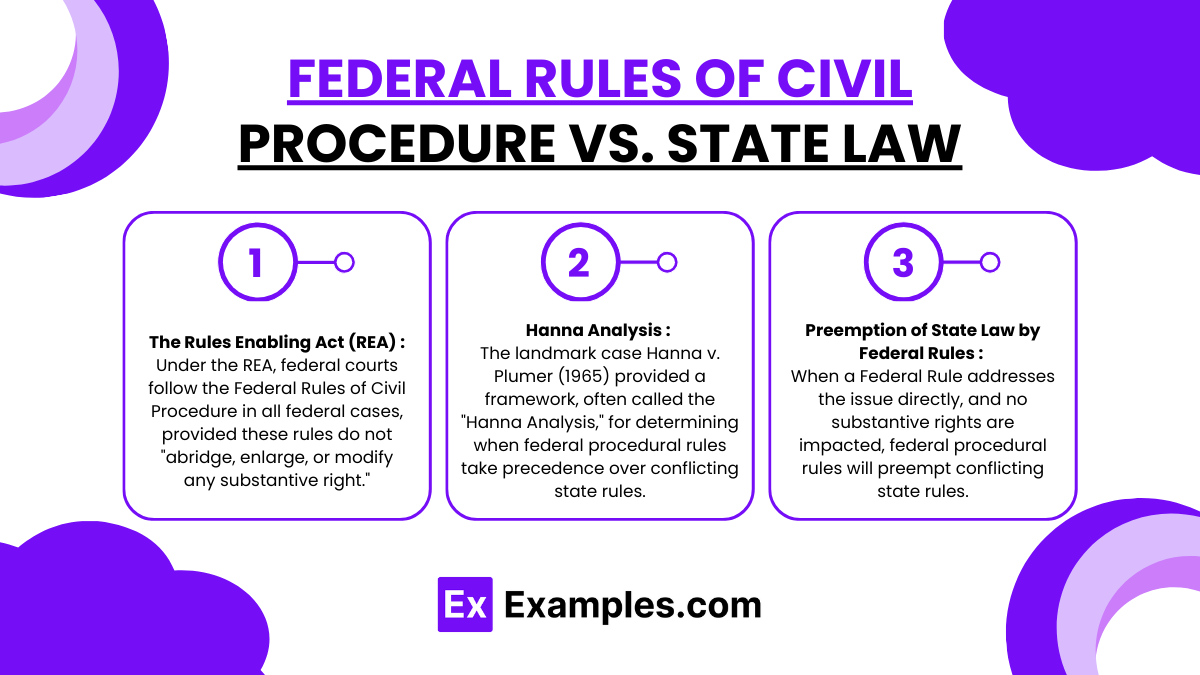

The Rules Enabling Act (REA): Under the REA, federal courts follow the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure in all federal cases, provided these rules do not "abridge, enlarge, or modify any substantive right." This ensures that procedural uniformity doesn’t infringe upon substantive rights.

Do not abridge, enlarge, or modify any substantive right. This phrase establishes an essential boundary that ensures the rules remain procedural in nature and do not encroach upon substantive legal rights that are traditionally the domain of state law.

Maintain procedural uniformity across federal courts, creating a streamlined, predictable process that does not vary by district.

Hanna Analysis: The landmark case Hanna v. Plumer (1965) provided a framework, often called the "Hanna Analysis," for determining when federal procedural rules take precedence over conflicting state rules. This analysis involves several steps:

Direct Conflict Requirement: The first question is whether there is a direct conflict between a Federal Rule of Civil Procedure and a state procedural rule. If no direct conflict exists, the court may apply both rules. However, if a conflict is present, further analysis is required.

Applying Federal Rules under the REA: If there is a direct conflict, the court examines whether the Federal Rule is within the scope of the REA.

Preemption of State Law by Federal Rules: When a Federal Rule addresses the issue directly, and no substantive rights are impacted, federal procedural rules will preempt conflicting state rules.

The REA grants federal courts procedural authority to override conflicting state rules where federal uniformity is essential for consistent administration of justice in federal courts.

The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure function as "supreme" procedural standards in federal courts. If a Federal Rule directly addresses a procedural issue, it will preempt state law unless it violates the REA or impacts substantive rights.

4. Federal Question Jurisdiction and Law Application

Federal Question Cases: In cases involving federal law under 28 U.S.C. § 1331, the federal court applies federal substantive law. For example, in federal statutes or constitutional questions, federal courts are bound to apply federal standards and precedents.

Federal Common Law: Although federal common law is limited, it still plays an essential role in specific types of cases where no federal statute applies but a need for federal uniformity exists. Federal common law is limited but still relevant in certain areas such as cases involving the rights and duties of the United States, disputes between states, or cases impacting international relations.

Supplemental Jurisdiction: Supplemental jurisdiction allows federal courts to hear additional state law claims that are closely related to a federal claim within the court’s jurisdiction. This can be particularly useful in cases with mixed claims, where both federal and state issues arise from the same set of facts.

5. Conflict of Laws in Federal Courts

Choice of Law in Federal Courts: When applying state law, federal courts typically follow the choice-of-law rules of the state in which they sit (per Klaxon Co. v. Stentor Electric Manufacturing Co.). This rule requires federal courts to apply state choice-of-law rules even if the underlying claim arises from another jurisdiction.

The Klaxon Rule: In diversity cases, federal courts must apply the choice-of-law rules of the state in which they sit, as established by the Supreme Court in Klaxon Co. v. Stentor Electric Manufacturing Co. (1941). This approach means that federal courts do not create their own choice-of-law rules but instead defer to the respective state’s rules, aligning with Erie Railroad Co. v. Tompkins to prevent federal courts from altering the outcome by applying different substantive laws.

Application Across Jurisdictions: Even when the federal court is addressing a case that involves parties or issues from multiple states, it will still follow the choice-of-law rules of the forum state (the state where the court is located). These rules determine which state’s substantive law applies and can vary significantly from state to state. For example, some states prioritize the place of injury or harm, while others focus on the location of the defendant’s conduct or the domicile of the parties.

Implications for MBE Questions: On the MBE, understanding the Klaxon Rule’s impact is crucial. This means recognizing that in diversity cases, the federal court’s choice of law is driven by state rules, and it does not apply a separate federal standard.

Federal Court’s Role in Interstate Conflicts: Federal courts balance principles of fairness and policy considerations when choosing which state’s law to apply, considering whether the parties have sufficient contacts with the states involved.

Balancing Fairness and Policy Considerations: When choosing which state’s law to apply, federal courts consider principles of fairness, judicial efficiency, and respect for state sovereignty. The court examines whether the chosen state law aligns with the expectations of the parties and the substantive interests of the states involved.

Significant Contacts Test: Federal courts often evaluate whether the parties have sufficient contacts with the states whose laws are in contention. For instance, in a contract dispute, relevant contacts could include the place where the contract was negotiated, executed, or performed. In a tort case, it could include the location of the alleged wrongdoing or the residence of the parties.

Avoiding Forum Shopping: Federal courts are cautious to avoid forum shopping—a practice where parties might choose a federal or state court based on perceived advantages in a particular jurisdiction’s substantive law. Applying state choice-of-law rules in diversity cases discourages forum shopping by ensuring that a litigant does not benefit unfairly from filing in federal court rather than state court.

Examples

Example 1: The Erie Doctrine in Action

In a diversity case where a plaintiff sues for personal injury in federal court, the court must decide whether to apply a state law that sets a cap on damages for pain and suffering. Since the state cap is considered a substantive rule (it directly affects the amount a plaintiff can recover), the court, following the Erie doctrine, applies the state’s damage cap. This example illustrates the Erie Doctrine’s requirement for federal courts to apply state substantive law in diversity cases, preventing a plaintiff from avoiding the cap by filing in federal court.

Example 2: Federal Procedural Rules Prevailing Over State Rules

A federal court sitting in diversity jurisdiction must determine whether to follow the state’s rule, which allows only 10 days for filing an answer, or the Federal Rule of Civil Procedure, which allows 21 days. Here, the court applies the federal rule under Hanna v. Plumer, as it is a procedural matter directly addressed by the Federal Rules. This example demonstrates how federal procedural rules take precedence in cases where federal and state procedural rules conflict, provided that the federal rule complies with the Rules Enabling Act.

Example 3: Outcome-Determinative Test

In a case involving a state law claim brought in federal court under diversity jurisdiction, the court must decide whether to apply a federal or state statute of limitations. According to the outcome-determinative test from Guaranty Trust Co. v. York, the court applies the state statute of limitations because using a different time limit would affect the outcome (determining whether the case can proceed). This test is essential for deciding whether a rule should be considered substantive and therefore governed by state law.

Example 4: Application of State Choice-of-Law Rules

A federal court in New York, hearing a case under diversity jurisdiction, must decide which state law to apply when an accident occurred in New Jersey, but both parties are residents of New York. Following Klaxon Co. v. Stentor Electric Manufacturing Co., the court applies New York’s choice-of-law rules, as required in diversity cases. This example demonstrates how federal courts use the choice-of-law rules of the state in which they sit, ensuring that cases are not decided differently based on the federal forum.

Example 5: Byrd Balancing Test for Procedural Rules

In a federal diversity case, the question arises whether to use a federal standard or a state rule requiring a different standard for a jury trial. Under Byrd v. Blue Ridge Rural Electric Cooperative, Inc., the court weighs the federal interest in maintaining a uniform standard for jury trials against the state’s interest in its rule. If the federal interest is stronger, the court may apply federal procedural rules despite the state standard. This example illustrates the Byrd balancing test, which helps federal courts determine whether federal procedural rules or state rules apply based on the strength of each interest.

Practice Questions

Question 1

In a diversity case heard in federal court, the plaintiff seeks damages for breach of contract. The statute of limitations for breach of contract claims is five years under the applicable state law, but only three years under federal procedural rules. The claim was filed after four years. Which statute of limitations should the federal court apply?

A. The federal court should apply the three-year statute of limitations under federal procedural rules.

B. The federal court should apply the five-year statute of limitations under state law because it is substantive.

C. The federal court should apply whichever statute of limitations is outcome-determinative.

D. The federal court has discretion to choose between the state and federal statute of limitations.

Answer: B

Explanation: In diversity cases, under the Erie Doctrine, federal courts apply state substantive law and federal procedural law. The statute of limitations is generally considered substantive because it affects the outcome of the case. If applying the federal rule would lead to a different outcome, the court should apply the state law. Here, the state law provides a five-year statute of limitations, which is longer than the federal procedural rule. Applying the state law aligns with the Erie Doctrine’s goal to prevent forum shopping and ensure equitable administration. Therefore, the court should apply the five-year state statute of limitations.

Question 2

A federal court sitting in diversity is deciding whether to apply a federal rule or a conflicting state rule. The federal rule promotes efficiency in court procedures, while the state rule provides specific protections for local residents. Which test should the court use to determine whether to apply the state rule?

A. Outcome-determinative test

B. Balance of interests test

C. Supremacy Clause test

D. Full faith and credit test

Answer: B

Explanation: The Balance of Interests Test, established in Byrd v. Blue Ridge Rural Electric Cooperative, Inc., requires the court to weigh the state’s interest in applying its law against the federal interest in following its own procedural rules. When there is a conflict between state and federal rules, and neither is strictly substantive or procedural, the federal court will use this test to determine which law to apply. Since the state rule provides specific protections for local residents, it shows a significant state interest. The federal rule promotes procedural efficiency, which is an important but more general interest. Here, the balance of interests test helps the court decide whether the state’s protections are more important than the federal procedural efficiency.

Question 3

A plaintiff files a contract dispute in federal court based on diversity jurisdiction. The federal court must determine which state’s law to apply in interpreting the contract terms. What rule should the court use to decide which state law applies?

A. The court should apply the choice-of-law rules of the state in which the federal court is located.

B. The court should apply federal common law choice-of-law rules.

C. The court has discretion to choose any state law that it deems fair.

D. The court should use the law of the state where the defendant resides.

Answer: A

Explanation: Under Klaxon Co. v. Stentor Electric Manufacturing Co., a federal court sitting in diversity jurisdiction applies the choice-of-law rules of the state in which it sits. This means that the federal court follows the forum state’s approach to decide which state’s substantive law to apply. Federal courts do not apply federal common law choice-of-law rules in diversity cases because doing so would undermine the goals of the Erie Doctrine. Here, the federal court will use the forum state’s choice-of-law rules to determine which state’s substantive law applies to the contract interpretation.