Pretrial procedures are critical steps in civil litigation, designed to structure, clarify, and potentially resolve disputes before a trial begins. These steps include pleadings, motions, discovery, and pretrial conferences, each governed by specific rules aimed at streamlining the process and reducing surprises. By exchanging information and narrowing issues, pretrial procedures help parties build their cases and explore settlement options, often avoiding trial altogether. Understanding these procedures is essential for effective case management and strategic planning, setting a strong foundation for any trial phase.

Learning Objectives

In studying "Pretrial Procedures" for the MBE Exam, you should learn to understand the stages and strategic goals of pretrial procedures, including pleadings, motions, and discovery. Examine how these elements frame the case and streamline issues before trial. Evaluate key discovery tools such as interrogatories, depositions, and requests for production, and understand the purpose of motions like motions to dismiss and for summary judgment. Explore pretrial conferences, their role in case management, and settlement facilitation. Additionally, analyze how these procedures prepare a case for trial and apply your knowledge to interpret procedural scenarios in practice questions.

Key Components of Pretrial Procedures

Pretrial procedures in civil litigation play a crucial role in setting the foundation for a fair and efficient trial. They aim to streamline the issues, preserve evidence, and encourage settlement. Mastery of these procedures is essential as it can significantly impact the progression and outcome of a case. Here are Key Components of Pretrial Procedures.

Pleadings

In civil procedure, pleadings refer to the formal written documents filed by parties in a lawsuit to outline their claims and defenses. These documents establish the foundation of the case by detailing the allegations, legal arguments, and facts each side intends to prove.

Types:

Complaint: The plaintiff’s initial statement of claims, which must include jurisdiction, a statement of facts, and the relief sought.

Answer: The defendant’s response to the complaint, addressing each allegation and presenting defenses.

Reply: In certain cases, the plaintiff may need to respond to new matters raised in the defendant's answer.

Amendments: The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP) allow amendments to pleadings for accuracy or clarification, under specific conditions.

Motions

A motion is a formal request made to the court by a party in a lawsuit, asking the court to issue an order or ruling on a specific issue related to the case. Motions can address a wide range of procedural and substantive matters at various stages of litigation, especially during pretrial proceedings.

Motions to Dismiss: A defendant may file a motion to dismiss based on issues like lack of jurisdiction, failure to state a claim, or improper venue. The court evaluates these motions before proceeding to trial.

Summary Judgment: Either party can move for summary judgment if there's no genuine dispute as to any material fact, and they are entitled to judgment as a matter of law. Summary judgment resolves cases without a trial if the facts are undisputed.

Discovery

Discovery is the process by which parties exchange information to uncover relevant facts and prepare for trial. It aims to prevent surprises and ensure fair treatment.

Types of Discovery Tools:

Interrogatories: Written questions that the opposing party must answer under oath.

Depositions: Out-of-court oral testimonies of witnesses or parties, taken under oath.

Requests for Production: Requests for documents, electronically stored information, and tangible evidence.

Requests for Admission: Requests to admit the truth of certain facts, narrowing the issues for trial.

Physical or Mental Examinations: Ordered by the court when the physical or mental condition of a party is at issue.

Scope and Limits: Discovery must be relevant to any party’s claim or defense and proportional to the needs of the case. Privileges, such as attorney-client privilege, limit discovery.

Pretrial Conferences and Orders

Scheduling Conference: Establishes the timeline for completing discovery, filing motions, and other pretrial activities.

Final Pretrial Conference: Held close to the trial date to finalize issues, witness lists, and exhibit lists. A pretrial order is issued, outlining what will be addressed at trial.

Purpose: These conferences foster settlement and enhance trial efficiency by narrowing issues and setting procedural rules.

Settlement and Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR)

Negotiation and Settlement: Throughout the pretrial stage, parties may engage in settlement discussions. Settlement can avoid the cost, time, and uncertainty of trial.

Mediation: A neutral mediator facilitates a voluntary agreement between parties. While not binding, mediation can result in settlement.

Arbitration: A more formal ADR method where an arbitrator hears evidence and makes a binding decision. Arbitration is less common for pretrial civil procedures but may be stipulated by contract.

Rules Governing Pretrial Procedures

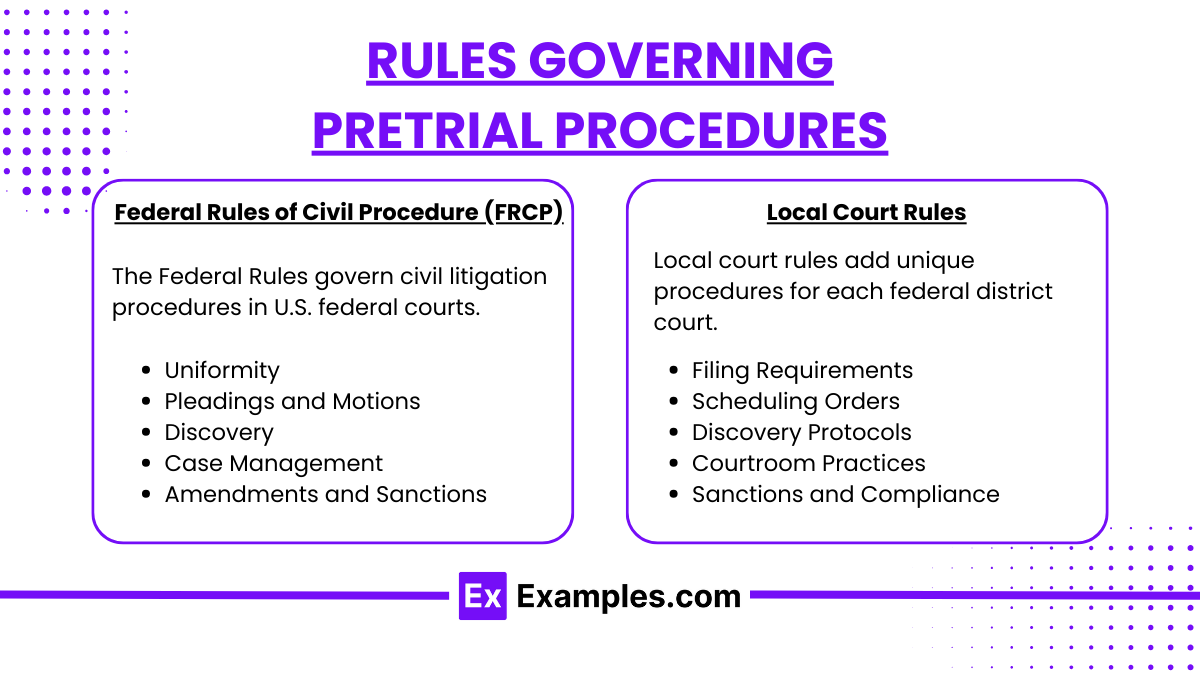

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP)

The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP) are a set of rules that govern civil litigation in federal courts across the United States. They outline the procedures for all stages of civil cases, including pleadings, motions, discovery, trials, and appeals. Key aspects of the FRCP include:

Uniformity: The FRCP ensures that civil litigation procedures are consistent across all federal courts, providing predictability and stability to the judicial process.

Pleadings and Motions: The FRCP specifies the types and requirements of pleadings (complaints, answers, etc.) and motions (e.g., motions to dismiss, motions for summary judgment). These rules dictate how parties must formally state their claims, defenses, and requests for court action.

Discovery: The FRCP governs the scope, types, and limits of discovery, detailing the rules for depositions, interrogatories, requests for production, and requests for admission. It includes provisions to prevent abusive practices, such as overly broad discovery requests, by setting standards for relevance and proportionality.

Case Management: The FRCP establishes guidelines for pretrial conferences and case management to streamline the litigation process, minimize delays, and facilitate settlement discussions when possible.

Amendments and Sanctions: The rules allow parties to amend pleadings within specified limits and detail the circumstances under which courts can impose sanctions for non-compliance, such as failure to provide discovery or bad-faith actions.

Local Court Rules

Local court rules are supplementary procedural requirements specific to each federal district court. They provide additional details, often tailored to the practices and needs of a particular court, and may vary widely between jurisdictions. Key aspects of local rules include:

Filing Requirements: Local rules specify unique requirements for submitting documents, including format, electronic filing protocols, and deadlines that align with the court's operational needs.

Scheduling Orders: Local rules can affect the scheduling of hearings, motion practice, and other pretrial events. Some districts may require additional conferences or have specific deadlines for the submission of certain documents.

Discovery Protocols: While FRCP rules set the foundation for discovery, local rules may establish specific practices, such as limits on the number of depositions, timeframes for responding to discovery requests, or mandatory disclosure requirements unique to that district.

Courtroom Practices: Each district court may have its own rules for court conduct, attire, communication with court staff, and other protocols aimed at maintaining decorum and efficiency in court proceedings.

Sanctions and Compliance: Local rules may outline sanctions for non-compliance with local requirements, such as failure to follow electronic filing protocols, missed deadlines, or other procedural missteps. Courts may use these sanctions to ensure adherence to both the FRCP and local rules.

Key Strategies for MBE Success on Pretrial Procedures

Memorize Deadlines: Know time limits for responding to pleadings, filing motions, and meeting discovery deadlines.

Understand Jurisdictional and Procedural Rules: Ensure clarity on when and how different motions (e.g., motion to dismiss, motion for summary judgment) are filed and argued.

Differentiate Between Types of Discovery: Be familiar with each type of discovery tool and when each is appropriate.

Practice Applying Rules to Scenarios: For example, know the proper response if one party fails to comply with a discovery request, including available sanctions and court orders.

Focus on Judicial Discretion: Recognize the broad discretion judges have during the pretrial process, especially in managing discovery and pretrial conferences.

Examples

Example 1. Motion to Dismiss for Lack of Personal Jurisdiction

Consider a case where a California resident sues a Florida company in California state court. The Florida company files a motion to dismiss, arguing that it lacks sufficient contacts with California to establish personal jurisdiction. Here, the court will examine whether exercising jurisdiction would violate due process. The MBE might ask about the standards for personal jurisdiction, such as minimum contacts, purposeful availment, and whether the defendant reasonably anticipated being haled into the court.

Example 2. Discovery Request for Production of Documents

In a breach of contract case, the plaintiff requests all emails between the defendant and a third party regarding the contract terms. The defendant objects, arguing that some emails contain privileged attorney-client communications. This example involves issues surrounding discovery requests, including relevance, scope, and privilege. MBE questions on this topic may test the conditions under which privileged information can be withheld and the procedure for challenging objections in discovery.

Example 3. Summary Judgment Motion in Negligence Case

A defendant in a negligence suit files for summary judgment, claiming that the plaintiff lacks evidence of causation, an essential element of negligence. The defendant argues that no genuine dispute of material fact exists and that they are entitled to judgment as a matter of law. For the MBE, a question might test your knowledge of summary judgment standards, such as the burden of proof in establishing the absence of material fact, as well as the need for the plaintiff to produce specific evidence to overcome the motion.

Example 4. Interrogatories Served to Establish Facts

In a contract dispute, the plaintiff serves the defendant with interrogatories asking for a detailed explanation of how the defendant interprets each contractual term. The defendant answers these questions under oath. This pretrial procedure highlights the role of interrogatories as a discovery tool to obtain specific facts from the opposing party. The MBE may present questions about the scope, limits, and permissible use of interrogatories, including potential sanctions for noncompliance or evasive answers.

Example 5. Final Pretrial Conference Order Detailing Issues for Trial

Before trial, both parties attend a final pretrial conference to streamline the issues, list witnesses, and mark exhibits. The court issues a pretrial order that outlines the exact issues for trial, effectively limiting what each party can argue. In an MBE question, you might be asked about the binding nature of pretrial orders and the circumstances under which a party may seek modification, emphasizing the role of pretrial conferences in ensuring an efficient and fair trial process.

Practice Questions

Question 1

A plaintiff files a lawsuit in federal court against a defendant. The defendant believes that the plaintiff’s complaint fails to state a claim upon which relief can be granted. Which of the following motions should the defendant file?

A. Motion for Summary Judgment

B. Motion to Strike

C. Motion to Dismiss under Rule 12(b)(6)

D. Motion for a More Definite Statement

Answer: C. Motion to Dismiss under Rule 12(b)(6)

Explanation: The correct answer is C. Under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 12(b)(6) allows a party to file a motion to dismiss when the complaint fails to state a claim upon which relief can be granted. This is often used when a defendant believes that, even if all allegations in the complaint are true, the plaintiff has not presented a legally sufficient basis to proceed with the lawsuit.

Option A (Motion for Summary Judgment): A motion for summary judgment is filed when there is no genuine dispute as to any material fact and the movant is entitled to judgment as a matter of law. It is typically filed after some discovery has taken place.

Option B (Motion to Strike): A motion to strike is used to remove specific allegations from pleadings that are irrelevant or prejudicial. It does not dismiss the entire complaint.

Option D (Motion for a More Definite Statement): This motion is used when a pleading is so vague or ambiguous that the opposing party cannot reasonably respond. It does not address whether the complaint states a valid legal claim.

In this scenario, the appropriate action for the defendant is to file a motion to dismiss under Rule 12(b)(6), which specifically addresses the sufficiency of the plaintiff’s claim.

Question 2

During discovery, the plaintiff in a personal injury case serves interrogatories on the defendant, asking for the names and addresses of all witnesses to the accident. The defendant responds by stating that the witnesses’ identities are protected as work product. The plaintiff files a motion to compel. How should the court likely rule?

A. Deny the motion because the witnesses’ identities are protected by attorney work-product privilege.

B. Grant the motion because the identities of witnesses are not protected by the work-product doctrine.

C. Deny the motion because the witnesses’ names are irrelevant to the plaintiff’s case.

D. Grant the motion only if the plaintiff can demonstrate undue hardship.

Answer: B. Grant the motion because the identities of witnesses are not protected by the work-product doctrine.

Explanation: The correct answer is B. Under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, the work-product doctrine generally protects materials prepared by or for an attorney in anticipation of litigation, such as notes, mental impressions, and strategy. However, it does not extend to basic information like the identities and contact information of witnesses.

Option A (Deny the motion because the witnesses’ identities are protected by attorney work-product privilege): The work-product doctrine does not cover facts or basic information that do not reflect an attorney’s mental impressions or legal theories.

Option C (Deny the motion because the witnesses’ names are irrelevant to the plaintiff’s case): Witness information is generally relevant in personal injury cases, as these individuals could provide testimony about the events in question.

Option D (Grant the motion only if the plaintiff can demonstrate undue hardship): This is incorrect, as the identities of witnesses are not work product, so the plaintiff does not need to show undue hardship to obtain this information.

The court is likely to grant the motion because the identities of witnesses are not considered privileged under the work-product doctrine.

Question 3

A plaintiff sues a defendant in federal court for breach of contract. Before trial, the defendant files a motion for summary judgment, asserting that there is no genuine issue of material fact and that the defendant is entitled to judgment as a matter of law. The plaintiff responds with an affidavit from a key witness that contradicts the defendant’s evidence. What is the likely outcome?

A. The motion for summary judgment will be granted because the defendant filed first.

B. The motion for summary judgment will be denied because the affidavit creates a genuine issue of material fact.

C. The motion for summary judgment will be granted unless the plaintiff provides additional documentary evidence.

D. The motion for summary judgment will be denied automatically because it is a pretrial motion.

Answer: B. The motion for summary judgment will be denied because the affidavit creates a genuine issue of material fact.

Explanation: The correct answer is B. In a summary judgment motion, the court determines whether there is a "genuine issue of material fact" that would warrant a trial. If the plaintiff presents an affidavit that contradicts the defendant’s version of events, this generally creates a factual dispute. Since summary judgment is only appropriate when there are no genuine disputes over material facts, the court will deny the motion in this case.

Option A (The motion for summary judgment will be granted because the defendant filed first): The timing of filing does not affect whether summary judgment is appropriate. The focus is on the presence or absence of factual disputes.

Option C (The motion for summary judgment will be granted unless the plaintiff provides additional documentary evidence): This is incorrect because an affidavit from a witness can be sufficient to create a genuine issue of fact.

Option D (The motion for summary judgment will be denied automatically because it is a pretrial motion): This is incorrect; summary judgment motions are intended to resolve cases pretrial if no factual disputes exist. The court will not deny the motion automatically just because it is filed before trial.

Therefore, the motion will likely be denied because the plaintiff’s affidavit introduces a factual dispute that must be resolved by a fact-finder at trial.