Remedies address the various means by which the law enforces rights and compensates for the violation of legal duties. This topic covers the primary types of remedies, including compensatory and punitive damages, equitable relief such as injunctions, and restitution. It emphasizes the principles guiding the availability and calculation of these remedies, as well as the circumstances under which specific types of relief are appropriate. A solid understanding of remedies is essential for assessing legal outcomes and the practical enforcement of judgments, providing a foundational element for navigating complex civil and contract cases.

Learning Objectives

In studying "Remedies" for the MBE, you should learn to identify and distinguish among the primary types of legal remedies, including compensatory damages, equitable relief, restitution, and punitive damages. Understand the specific criteria and limitations associated with each type, such as foreseeability, causation, and proportionality in damages awards. Analyze scenarios to determine the most appropriate remedy based on the nature of the harm and the legal principles involved. Evaluate equitable remedies like injunctions and specific performance, recognizing when they apply and their underlying requirements. Additionally, familiarize yourself with defenses that may limit or bar recovery, such as mitigation, unclean hands, and laches, to effectively analyze complex fact patterns in MBE questions.

Types of Legal Remedies: Compensatory Damages, Equitable Relief, Restitution, and Punitive Damages

Legal remedies are solutions provided by courts to address or redress harm or injury suffered by a party. The main types of legal remedies include compensatory damages, equitable relief, restitution, and punitive damages. Each type serves a unique purpose, whether it’s compensating the injured party, deterring wrongful conduct, or restoring the injured party to their original position. Here’s an overview of each type:

1. Compensatory Damages

Purpose: Compensatory damages are intended to make the injured party “whole” by financially compensating them for the losses directly resulting from the harm or injury caused by the defendant. This type of remedy aims to restore the injured party to the position they would have been in if the harm had not occurred.

Types:

General Damages: Cover non-economic losses, such as pain and suffering, emotional distress, or loss of enjoyment of life. These are harder to quantify, as they are subjective and depend on the extent of the injury.

Special Damages: Cover economic losses with a quantifiable value, such as medical bills, lost wages, property damage, and other out-of-pocket expenses.

Example: In a car accident case where one party is injured due to another’s negligence, compensatory damages could include payment for medical expenses, car repairs, and compensation for pain and suffering.

Limitations: Compensatory damages are designed to provide fair compensation but not to punish the defendant. They are limited to the actual loss suffered, meaning the plaintiff cannot receive more than the value of their losses.

Legal remedies are solutions provided by courts to address or redress harm or injury suffered by a party. The main types of legal remedies include compensatory damages, equitable relief, restitution, and punitive damages. Each type serves a unique purpose, whether it’s compensating the injured party, deterring wrongful conduct, or restoring the injured party to their original position. Here’s an overview of each type:

2. Equitable Relief

Purpose: Equitable relief, also known as an equitable remedy, is a non-monetary solution where the court orders the defendant to perform or refrain from performing a specific act. Equitable relief is often used when monetary compensation would not be adequate to resolve the harm.

Types:

Injunction: A court order that requires the defendant to stop engaging in certain actions or mandates that they perform a specific action. Injunctions are common in cases involving ongoing harm, such as intellectual property infringement or environmental violations.115

Specific Performance: An order requiring a party to fulfill their contractual obligations. This remedy is typically used in cases involving unique goods or property, such as real estate transactions, where monetary compensation wouldn’t suffice.

Declaratory Relief: A judgment from the court that determines the rights and obligations of the parties without requiring action or awarding damages. This remedy is common in cases involving contract interpretation or constitutional rights.

Example: In a case involving a breach of contract to sell a unique property, the court may order specific performance, requiring the seller to complete the sale instead of simply paying damages.

Limitations: Equitable relief is typically available only when monetary damages are insufficient to resolve the harm. Courts have discretion to deny equitable remedies if the plaintiff’s conduct is deemed unfair or if granting relief would cause undue hardship for the defendant.

3. Restitution

Purpose: Restitution aims to prevent the defendant from unjustly benefiting or profiting at the plaintiff's expense. The goal is to restore the plaintiff to the position they were in before the wrongful act occurred, often by requiring the defendant to return any gains or benefits they received from their misconduct.

Types:

Monetary Restitution: Requires the defendant to pay an amount equivalent to the benefit they wrongfully gained. This could include profits derived from a breach of fiduciary duty or unauthorized use of another’s property.

Restitution in Kind: In some cases, the court may require the return of specific property or assets, rather than a monetary equivalent, especially when the property has unique value.

Example: If someone receives payment for services they did not actually perform, a court might order them to return the money through monetary restitution.

Limitations: Restitution is not always available if the defendant did not derive any financial benefit from the misconduct. This remedy is focused on preventing unjust enrichment rather than compensating the plaintiff’s losses.

4. Punitive Damages

Purpose: Punitive damages are awarded to punish the defendant for particularly wrongful or egregious conduct and to deter similar behavior in the future. Unlike compensatory damages, which are designed to compensate the victim, punitive damages go beyond compensation and serve a disciplinary function.

Criteria: Punitive damages are typically awarded only in cases involving intentional misconduct, fraud, gross negligence, or reckless behavior. Courts may consider the defendant’s motives, the severity of the harm, and the need to send a message to deter similar conduct.

Example: In a case where a company knowingly sells a dangerous product without disclosing its risks, the court may award punitive damages to punish the company and deter other businesses from similar actions.

Limitations: Punitive damages are not available in every case and are often subject to limits, either set by statutes or by courts to avoid excessive penalties. In the U.S., the Supreme Court has ruled that punitive damages must be reasonable and proportionate to the compensatory damages awarded to avoid violating due process rights.

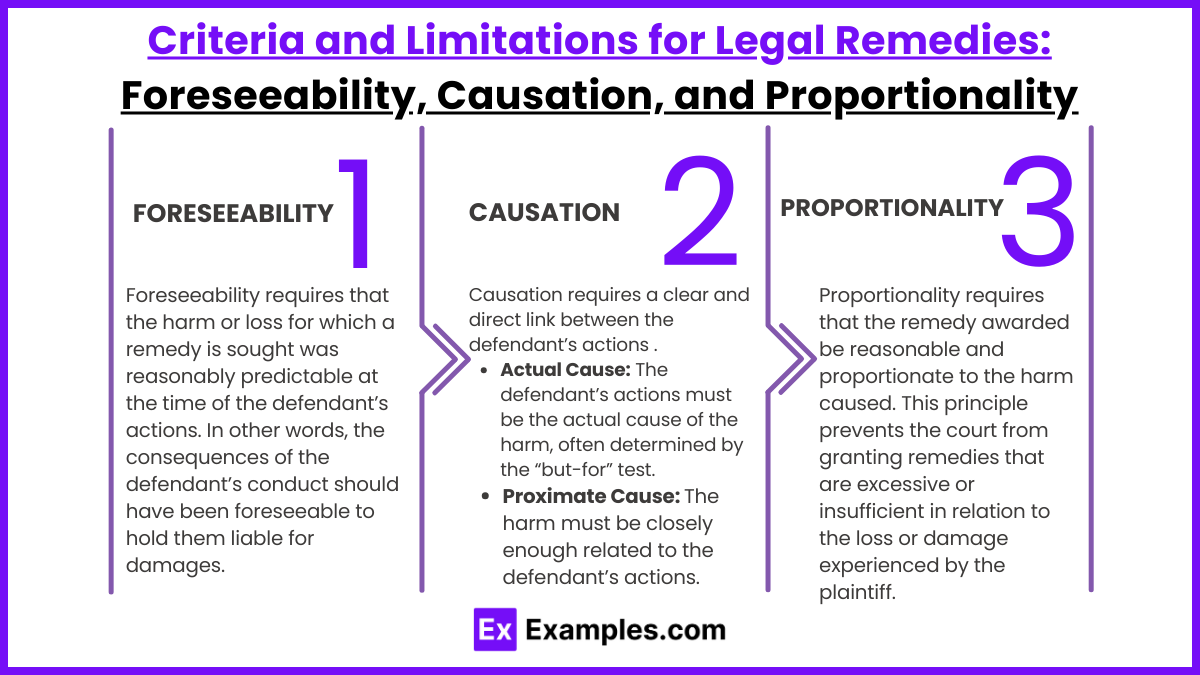

Criteria and Limitations for Legal Remedies: Foreseeability, Causation, and Proportionality

Legal remedies are subject to specific criteria and limitations to ensure that they are fair, appropriate, and effective. Key criteria such as foreseeability, causation, and proportionality help to determine the extent and type of remedy that may be awarded. Each criterion serves as a check to ensure remedies are reasonable and justifiable, preventing excessive or inadequate compensation or punishment. Here’s a closer look at each criterion and its limitations in the context of legal remedies:

1. Foreseeability

Definition: Foreseeability requires that the harm or loss for which a remedy is sought was reasonably predictable at the time of the defendant’s actions. In other words, the consequences of the defendant’s conduct should have been foreseeable to hold them liable for damages.

Application: Courts use foreseeability primarily in cases involving negligence or breach of contract. For instance, if the harm caused was a reasonably predictable outcome of the defendant's actions, the plaintiff may be eligible for remedies like compensatory damages.

Example: In a negligence case where a driver runs a red light and causes a pedestrian injury, it’s foreseeable that the driver’s actions could harm others. Thus, the driver could be liable for compensatory damages for the pedestrian’s injuries.

Limitations: Remedies are typically limited to foreseeable damages to prevent defendants from being held responsible for highly improbable or unexpected consequences. For example, if a defendant’s actions result in an unlikely series of events leading to harm, they may not be held liable for those damages.

Key Point: Foreseeability ensures that defendants are only responsible for harms they could reasonably anticipate, balancing accountability with fairness.

2. Causation

Definition: Causation requires a clear and direct link between the defendant’s actions and the plaintiff’s harm. Causation typically involves two aspects:

Actual Cause (Cause-in-Fact): The defendant’s actions must be the actual cause of the harm, often determined by the “but-for” test (e.g., the harm would not have occurred but for the defendant’s actions).

Proximate Cause (Legal Cause): The harm must be closely enough related to the defendant’s actions to hold them legally responsible. Proximate cause limits liability to situations where the harm is a direct and natural result of the defendant's conduct.

Application: Causation is a central criterion in awarding remedies in tort and contract cases. The court must find that the defendant’s actions were both the factual and legal cause of the plaintiff’s harm before granting compensatory damages.

Example: In a medical malpractice case, if a doctor’s misdiagnosis directly leads to a patient’s worsening condition, causation is established, and the patient may receive damages. However, if an unrelated factor worsened the patient’s condition, the doctor might not be held liable.

Limitations: Remedies are limited to harms directly caused by the defendant’s actions. If intervening events or third-party actions contribute to the harm, the defendant’s liability may be reduced or eliminated. Courts often look for a clear causal chain; if broken, the defendant may not be liable.

Key Point: Causation ensures that only those who are directly responsible for harm are held liable, preventing unjust or excessive compensation.

3. Proportionality

Definition: Proportionality requires that the remedy awarded be reasonable and proportionate to the harm caused. This principle prevents the court from granting remedies that are excessive or insufficient in relation to the loss or damage experienced by the plaintiff.

Application: Proportionality is essential in determining compensatory and punitive damages. Compensatory damages should correspond to the actual losses suffered, while punitive damages should be reasonable relative to the wrongdoing and compensatory award.

Example: In a defamation case, if a false statement results in a measurable financial loss for the plaintiff, compensatory damages should cover that specific amount. However, punitive damages would be awarded only if the defendant’s conduct was particularly egregious, and even then, they would need to be proportional to the harm caused.

Limitations:

Compensatory Damages: Limited to the actual loss suffered to avoid overcompensation. For example, if a plaintiff’s car sustains $5,000 in damage, compensatory damages cannot exceed that amount.

Punitive Damages: Courts often impose caps on punitive damages, ensuring they do not exceed a multiple of the compensatory damages (e.g., a 1:1 or 2:1 ratio) to prevent excessive punishment.

Equitable Relief: Proportionality applies to equitable remedies to ensure that they are neither excessively burdensome to the defendant nor insufficient to address the plaintiff’s harm.

Key Point: Proportionality protects against excessive remedies, ensuring that the punishment or compensation aligns reasonably with the harm or misconduct.

Determining the Appropriate Remedy Based on Harm and Legal Principles

Determining the appropriate remedy in a legal case requires careful consideration of the nature and extent of the harm suffered, along with key legal principles. Courts assess the specifics of each case, considering factors such as the type of harm (e.g., financial, physical, or emotional), the defendant’s intent, the foreseeability and causation of the harm, and whether monetary damages alone can adequately address the injury. Based on these factors, courts may award compensatory damages, equitable relief, restitution, or punitive damages. Here’s a step-by-step guide to understanding how courts determine the appropriate remedy:

1. Assessing the Type and Extent of Harm

Step: The court first examines the harm suffered by the plaintiff. The type of harm—whether it’s economic loss, physical injury, emotional distress, or reputational damage—will influence the choice of remedy.

Key Considerations:

Economic Harm: If the plaintiff suffered a calculable financial loss (e.g., medical bills, lost wages), compensatory damages are likely appropriate.

Non-Economic Harm: For harm that doesn’t have a direct financial cost (e.g., pain and suffering, emotional distress), general damages may be awarded as part of compensatory damages.

Ongoing or Future Harm: If the harm is continuing or likely to recur, the court may consider equitable relief, such as an injunction, to prevent further injury.

Example: In a car accident case involving physical injury and lost income, compensatory damages would typically cover medical costs, lost wages, and compensation for pain and suffering.

2. Applying Foreseeability

Step: The court evaluates whether the harm suffered was a foreseeable result of the defendant’s actions. Foreseeability ensures that the defendant is only held liable for consequences that could reasonably have been anticipated.

Key Considerations:

Negligence Cases: In negligence cases, if the harm was foreseeable, compensatory damages are usually awarded. If the harm was unforeseeable, the plaintiff may be ineligible for compensation.

Breach of Contract: In contract cases, foreseeability is also crucial; damages must be within what the parties could reasonably expect as a consequence of the breach.

Example: If a business fails to fulfill a contract, causing foreseeable financial losses to the other party, compensatory damages are likely appropriate to cover the predictable financial impact.

3. Establishing Causation

Step: Causation requires a clear, direct link between the defendant’s actions and the plaintiff’s harm. The court examines whether the defendant’s conduct was the actual and proximate cause of the injury.

Key Considerations:

Actual Cause (Cause-in-Fact): Would the harm have occurred “but for” the defendant’s actions?

Proximate Cause: Is the harm closely related enough to the defendant’s conduct to justify liability?

Example: In a medical malpractice case, the plaintiff must demonstrate that the doctor’s negligence directly caused their injury. If causation is proven, the appropriate remedy may include compensatory damages for medical expenses and suffering.

4. Evaluating Proportionality

Step: Proportionality requires that the remedy awarded aligns reasonably with the harm caused. Courts aim to ensure that the remedy is neither excessive nor insufficient relative to the injury.

Key Considerations:

Compensatory Damages: Should match the actual loss suffered, covering both direct financial losses and, where applicable, non-economic damages.

Punitive Damages: If the defendant’s conduct was egregious, punitive damages may be awarded, but they must be proportionate to the harm and serve as a reasonable deterrent.

Equitable Remedies: If money alone cannot address the harm, equitable relief, such as an injunction or specific performance, may be granted, but it must not impose an undue burden on the defendant.

Example: In a defamation case that causes reputational harm, compensatory damages may be awarded to match the plaintiff’s financial losses. If the defendant’s conduct was particularly malicious, the court may also award proportionate punitive damages.

5. Choosing the Type of Remedy Based on Legal Principles

Compensatory Damages:

When Appropriate: Used to compensate the plaintiff for specific, quantifiable losses resulting from the defendant’s conduct.

Example: In a breach of contract case, compensatory damages can cover the plaintiff’s lost profits or costs incurred due to the breach.

Equitable Relief:

When Appropriate: If monetary compensation is inadequate to address the harm or stop ongoing harm, the court may issue an injunction or order specific performance.

Example: In a case involving intellectual property infringement, an injunction may prevent further unauthorized use, while specific performance could compel a party to complete a unique contract (e.g., transferring a rare asset).

Restitution:

When Appropriate: When the defendant has unjustly profited at the plaintiff’s expense, restitution may be ordered to restore the plaintiff’s position.

Example: In cases of fraud, the court may order the defendant to return profits obtained through deception.

Punitive Damages:

When Appropriate: Reserved for cases involving willful, malicious, or particularly reckless conduct. These damages punish the defendant and deter similar behavior.

Example: If a manufacturer knowingly sells a harmful product without disclosure, punitive damages may be awarded in addition to compensatory damages.

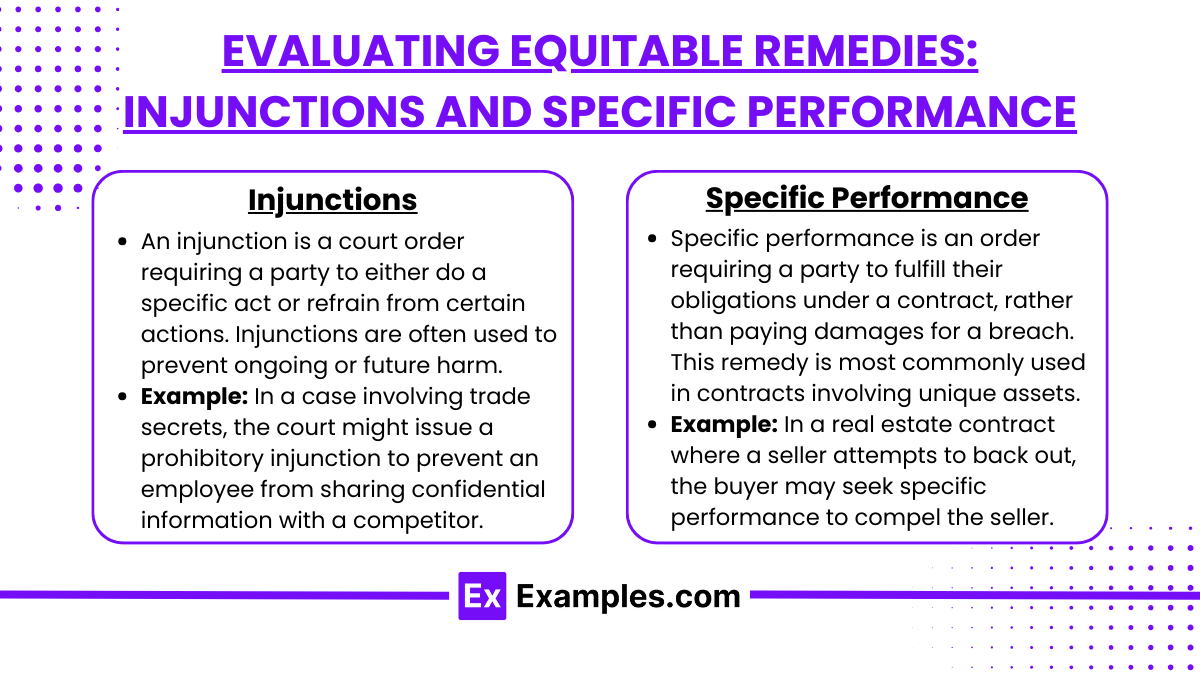

Evaluating Equitable Remedies: Injunctions and Specific Performance

Equitable remedies, such as injunctions and specific performance, are non-monetary court-ordered actions designed to address situations where monetary compensation alone is insufficient to resolve harm. These remedies are particularly relevant in cases involving unique assets, ongoing harms, or breaches of contract where damages would not fully address the plaintiff’s loss. Courts grant these remedies based on specific criteria, including the inadequacy of monetary damages, the uniqueness of the subject matter, and the balance of hardships between the parties. Here’s a detailed evaluation of injunctions and specific performance:

1. Injunctions

Definition: An injunction is a court order requiring a party to either do a specific act (mandatory injunction) or refrain from certain actions (prohibitory injunction). Injunctions are often used to prevent ongoing or future harm.

Types of Injunctions:

Temporary (Preliminary) Injunction: A short-term injunction granted early in a case to prevent imminent harm until a final decision is made. This type of injunction is usually issued when immediate action is necessary to protect the plaintiff’s rights.

Permanent Injunction: A long-term injunction granted after the conclusion of a case, permanently prohibiting or mandating a specific action if the court determines that ongoing harm would occur without it.

Criteria for Granting an Injunction:

Inadequacy of Monetary Damages: The harm must be such that financial compensation alone would not fully resolve it. For example, in cases of intellectual property infringement, the harm to the plaintiff’s reputation or competitive edge might require stopping the infringing activity rather than a monetary settlement.

Irreparable Harm: The plaintiff must demonstrate that without the injunction, they would suffer harm that cannot be remedied by damages, such as environmental destruction or loss of trade secrets.

Likelihood of Success on the Merits: For a preliminary injunction, the court assesses whether the plaintiff is likely to win the case, as this indicates the injunction’s justification.

Balance of Hardships: The court weighs the potential harm to the plaintiff if the injunction is denied against the burden it would impose on the defendant if granted.

Public Interest: Courts also consider whether granting the injunction would serve or harm the public interest, especially in cases affecting public health, safety, or welfare.

Example: In a case involving trade secrets, the court might issue a prohibitory injunction to prevent an employee from sharing confidential information with a competitor, as monetary damages alone may not sufficiently protect the business’s proprietary information.

Limitations of Injunctions:

Injunctions are discretionary and may be denied if they would impose an undue burden on the defendant or if the plaintiff has “unclean hands,” meaning the plaintiff acted unethically or in bad faith.

Courts are cautious in issuing injunctions in cases where they would require ongoing supervision or detailed oversight, as these can be challenging to enforce.

2. Specific Performance

Definition: Specific performance is an order requiring a party to fulfill their obligations under a contract, rather than paying damages for a breach. This remedy is most commonly used in contracts involving unique items or assets, such as real estate or rare goods, where substitute performance would not be adequate.

Criteria for Granting Specific Performance:

Uniqueness of the Subject Matter: Specific performance is typically granted when the contract involves unique or irreplaceable items, such as real estate, heirlooms, or rare art. Real estate is considered inherently unique, making specific performance a common remedy in property transactions.

Inadequacy of Monetary Damages: Monetary damages must be insufficient to put the plaintiff in the position they would have been in had the contract been performed. If an item is unique and difficult to replace, money alone may not be enough.

Certainty of Contract Terms: The contract must be clear, specific, and enforceable, with defined obligations for both parties. Vague or ambiguous contracts are unlikely to qualify for specific performance, as they are challenging for courts to enforce.

Feasibility of Enforcement: Specific performance will not be granted if enforcing the order would be impractical or if it would require extensive, ongoing court supervision. Courts prefer to avoid remedies that necessitate close oversight.

Plaintiff’s Clean Hands: The plaintiff must not have engaged in unethical or unfair conduct in relation to the contract. This principle, known as “clean hands,” prevents plaintiffs from using specific performance if they acted in bad faith.

Example: In a real estate contract where a seller attempts to back out, the buyer may seek specific performance to compel the seller to transfer the property, as monetary damages would not compensate for the loss of that unique property.

Limitations of Specific Performance:

Specific performance is generally unavailable in contracts for personal services, as forcing someone to work against their will is both impractical and contrary to public policy.

Courts may deny specific performance if damages are sufficient or if enforcing the contract would place undue hardship on the defendant.

If the contract terms are unclear or the agreement lacks specificity, specific performance is unlikely to be awarded, as courts require clear terms to enforce an order.

Examples

Example 1: Legal Remedies in Contract Disputes

In legal contexts, remedies are solutions provided to a party that has been harmed due to a breach of contract. These remedies may include compensatory damages, which aim to restore the injured party to the position they would have been in if the contract had been fulfilled. Other legal remedies could include specific performance, where the court orders the breaching party to fulfill their contractual obligations.

Example 2: Medical Remedies for Illnesses

In medicine, remedies refer to treatments or therapies used to alleviate or cure physical ailments. For example, antibiotics are used as a remedy for bacterial infections, while antiviral medications help treat viral infections. These remedies aim to restore the patient to health and prevent further complications or spread of disease.

Example 3: Remedies for Environmental Damage

Environmental remedies are measures taken to address damage to ecosystems, such as pollution or deforestation. This can include the cleanup of hazardous waste sites, reforestation programs, or the restoration of water quality in polluted rivers. These actions aim to restore environmental health and protect biodiversity for future generations.

Example 4: Financial Remedies for Economic Loss

In the context of personal finance, remedies might refer to steps taken to recover from financial loss or hardship. For example, someone who has fallen into debt due to unforeseen circumstances may seek remedies through debt consolidation, bankruptcy filing, or financial counseling to regain financial stability and address outstanding obligations.

Example 5: Psychological Remedies for Stress

In the realm of mental health, remedies refer to techniques or therapies used to reduce stress, anxiety, or depression. Remedies may include counseling, mindfulness practices, exercise, or medications such as antidepressants. These interventions help individuals regain emotional balance and improve overall well-being, allowing them to cope with life’s challenges more effectively.

Practice Questions

Question 1

Which of the following is an example of a legal remedy in a contract dispute?

A) An apology from the breaching party

B) A court order to perform the contract as agreed

C) Compensation for lost wages

D) A change in the contract terms

Correct Answer: B) A court order to perform the contract as agreed.

Explanation: A legal remedy for a contract dispute can include specific performance, where the court orders the breaching party to perform their obligations as outlined in the contract. This remedy is often used when monetary compensation is not sufficient to resolve the issue. While compensation for lost wages is a remedy, it applies to damages, not performance of the contract. The other options do not represent typical legal remedies for breaches of contract.

Question 2

Which of the following is a medical remedy for a bacterial infection?

A) Pain relievers

B) Antibiotics

C) Antidepressants

D) Antihistamines

Correct Answer: B) Antibiotics.

Explanation: Antibiotics are a medical remedy specifically designed to treat bacterial infections by killing bacteria or inhibiting their growth. Pain relievers (like ibuprofen) can help with symptoms but do not treat the underlying cause of the infection. Antidepressants and antihistamines are remedies for mental health issues and allergies, respectively, but are not used for bacterial infections.

Question 3

What is a common financial remedy for someone facing significant debt?

A) Starting a new job

B) Filing for bankruptcy

C) Cutting personal expenses

D) Changing your investment strategy

Correct Answer: B) Filing for bankruptcy.

Explanation: Filing for bankruptcy is a legal remedy for individuals facing significant financial debt. It allows them to discharge some or all of their debts or reorganize them, providing relief from creditors. While cutting expenses or changing investment strategies may help improve financial situations, they are not formal financial remedies like bankruptcy, which provides legal protection and a structured resolution. Starting a new job, while helpful, is not considered a remedy in this context.