Understanding gastrointestinal (GI) disorders and nutritional needs in children is critical for the NCLEX-RN®. The pediatric GI system has unique anatomical and physiological differences compared to adults, and children’s nutritional needs vary significantly with age. This knowledge enables nurses to provide safe, effective care and parental guidance.

Learning Objectives

In studying Gastrointestinal/Nutrition for the NCLEX-RN® exam, you should learn to assess and manage common pediatric gastrointestinal conditions, including gastroesophageal reflux, intussusception, and celiac disease. Understand the nutritional needs across developmental stages, from infancy to adolescence, and evaluate appropriate feeding practices, including breastfeeding, formula feeding, and solid food introduction. Analyze signs and symptoms of malnutrition, dehydration, and dietary-related conditions like failure to thrive or iron-deficiency anemia. Additionally, explore interventions to prevent obesity and promote healthy eating habits. Apply this knowledge to interpret patient scenarios, prioritize nursing care, and provide education for families in both acute and community settings.

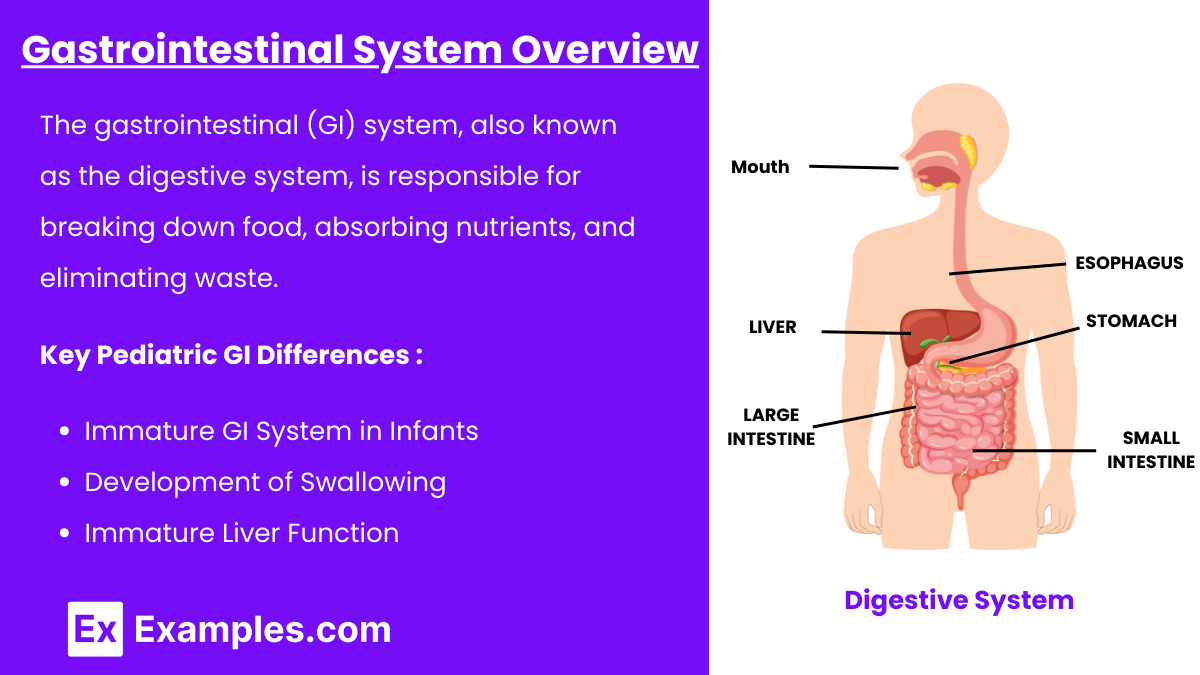

Gastrointestinal System Overview

The gastrointestinal (GI) system, also known as the digestive system, is responsible for breaking down food, absorbing nutrients, and eliminating waste. It includes the mouth, esophagus, stomach, intestines, liver, pancreas, and other accessory organs. In pediatrics, the GI system undergoes significant development from birth to adolescence, and understanding its anatomy and physiology is essential for identifying and managing pediatric GI disorders.

Key Pediatric GI Differences

Immature GI System in Infants:

Stomach capacity is small; increases with age.

Enzymes for digestion (e.g., amylase, lipase) are immature until about 6 months.

Increased risk of dehydration due to higher metabolic rate and fluid turnover.

Development of Swallowing:

Fully coordinated swallowing develops at 6 months.

Immature Liver Function:

Reduced ability to metabolize drugs and bilirubin.

Common Pediatric GI Disorders

Gastroesophageal Reflux (GER)

Pathophysiology: Immaturity of the lower esophageal sphincter leads to reflux.

Symptoms: Spitting up, irritability, poor feeding, weight loss.

Management:

Small, frequent feedings.

Keep infant upright for 30 minutes post-feeding.

Use thickened formula if prescribed.

Severe cases: Medications like ranitidine or surgical intervention (Nissen fundoplication).

Pyloric Stenosis

Pathophysiology: Hypertrophy of the pyloric muscle obstructs gastric emptying.

Symptoms: Projectile vomiting, olive-shaped mass in RUQ, dehydration, weight loss.

Management: Surgical correction (pyloromyotomy).

Intussusception

Pathophysiology: Telescoping of one bowel segment into another.

Symptoms: Sudden abdominal pain, “currant jelly” stools, sausage-shaped mass in abdomen.

Management: Air or barium enema; surgery if enema fails.

Hirschsprung Disease

Pathophysiology: Absence of ganglion cells in the rectum and colon leads to motility issues.

Symptoms: Failure to pass meconium within 48 hours, abdominal distension, constipation.

Management: Surgical removal of the aganglionic segment.

Celiac Disease

Pathophysiology: Gluten intolerance leading to malabsorption.

Symptoms: Diarrhea, steatorrhea, failure to thrive, irritability.

Management: Lifelong gluten-free diet (avoid wheat, barley, rye, oats).

Appendicitis

Pathophysiology: Inflammation of the appendix due to obstruction.

Symptoms: RLQ pain (McBurney's point), fever, nausea, vomiting.

Management: Appendectomy.

Diarrhea and Dehydration

Causes: Infections, malabsorption, or food intolerances.

Assessment: Sunken fontanel, decreased skin turgor, dry mucous membranes, weight loss.

Management:

Oral rehydration solutions (ORS) for mild to moderate dehydration.

IV fluids for severe dehydration.

Monitor electrolyte imbalances (e.g., potassium).

Nutrition Across Developmental Stages

1. Infancy (Birth to 1 Year)

Breastfeeding: Ideal nutrition; exclusive for the first 6 months.

Formula Feeding: Use iron-fortified formula if not breastfeeding.

Introducing Solids: Start at 4-6 months with iron-fortified cereals, followed by pureed vegetables, fruits, and proteins. Avoid honey (risk of botulism).

2. Toddler (1 to 3 Years)

Diet: Transition to whole milk after 12 months; limit to 24 oz/day to prevent iron-deficiency anemia.

Picky Eating: Common; encourage a balanced diet.

Risk: Choking on small foods (e.g., nuts, grapes, hot dogs).

3. Preschool (3 to 6 Years)

Diet: Balanced meals with fruits, vegetables, protein, and grains.

Behavior: Teach healthy eating habits; involve children in food preparation.

4. School-Age (6 to 12 Years)

Diet: Increased caloric needs due to growth spurts.

Focus: Prevent obesity by limiting sugary snacks and promoting physical activity.

5. Adolescence (12 to 18 Years)

Diet: High caloric and protein needs to support rapid growth and puberty.

Risks: Poor diet choices, eating disorders, and nutrient deficiencies (e.g., calcium, iron).

Nutritional Disorders

Failure to Thrive (FTT)

Definition: Inadequate growth due to insufficient nutrition or underlying medical conditions.

Assessment: Weight below the 5th percentile, developmental delays.

Management:

Assess feeding practices.

Address psychosocial factors.

Nutritional supplementation if needed.

Iron-Deficiency Anemia

Cause: Insufficient dietary iron (common in toddlers).

Symptoms: Fatigue, pallor, poor feeding.

Management: Iron-rich foods (meat, leafy greens) and supplements.

Obesity

Cause: High caloric intake, low physical activity.

Management: Family-centered lifestyle modifications, nutritional counseling.

Examples

Example 1. Pyloric Stenosis

A 4-week-old infant presents with projectile vomiting after feedings, poor weight gain, and irritability. The nurse notes an olive-shaped mass in the upper right quadrant of the abdomen during palpation. The priority is to assess hydration status, including fontanel condition and urine output, and prepare the child for surgical intervention (pyloromyotomy). Preoperative care includes keeping the infant NPO, placing an NG tube for decompression if necessary, and administering IV fluids to correct dehydration and electrolyte imbalances. Postoperatively, the nurse monitors for vomiting, manages pain, and educates the parents about gradual feeding reintroduction.

Example 2. Intussusception

A 12-month-old child is brought to the emergency room with intermittent abdominal pain, inconsolable crying, and "currant jelly" stools. During the abdominal assessment, a sausage-shaped mass is felt. The nurse prioritizes obtaining a focused history and preparing the child for a diagnostic and therapeutic air or barium enema. If the enema does not resolve the obstruction, surgical intervention may be necessary. Post-treatment, the nurse monitors for the recurrence of symptoms, ensures the return of normal bowel function, and educates caregivers on recognizing signs of recurrence.

Example 3. Celiac Disease

A 6-year-old child presents with chronic diarrhea, abdominal bloating, and failure to thrive. After a diagnosis of celiac disease through serologic tests and intestinal biopsy, the nurse provides education on a gluten-free diet. The nurse explains that foods containing wheat, barley, rye, and oats must be avoided and emphasizes alternatives like rice, corn, and quinoa. Regular monitoring of growth and nutritional status is essential. The nurse also provides guidance to parents on reading food labels and avoiding cross-contamination in food preparation.

Example 4. Failure to Thrive (FTT)

A 10-month-old infant has a weight below the 5th percentile and shows developmental delays. The nurse conducts a thorough assessment, including feeding practices, family interactions, and potential medical conditions contributing to the FTT. Nursing interventions include teaching parents appropriate feeding techniques, providing high-calorie and nutrient-dense formulas or supplements, and collaborating with social services if psychosocial factors are identified. The nurse also monitors the infant's weight gain and developmental progress during follow-up visits.

Example 5. Acute Gastroenteritis and Dehydration

A 2-year-old child is admitted with diarrhea, vomiting, and signs of dehydration, including sunken eyes, dry mucous membranes, and decreased urine output. The nurse prioritizes rehydration by administering oral rehydration solutions (ORS) for mild to moderate dehydration or IV fluids for severe cases. Monitoring includes checking electrolyte levels and urine output. The nurse educates parents on proper hand hygiene to prevent further infections, emphasizes the importance of maintaining hydration at home, and advises on the gradual reintroduction of a regular diet using the BRAT diet (bananas, rice, applesauce, toast) for recovery.

Practice Questions

Question 1

A 4-month-old infant presents with projectile vomiting after feeding and visible peristaltic waves across the abdomen. The nurse palpates an olive-shaped mass in the right upper quadrant. What is the priority nursing intervention?

A. Administer oral rehydration solution.

B. Prepare the infant for surgery.

C. Initiate a trial of thickened formula feedings.

D. Position the infant upright during and after feedings.

Answer: B. Prepare the infant for surgery.

Explanation: The symptoms described are classic for pyloric stenosis, a condition characterized by hypertrophy of the pyloric muscle that obstructs gastric emptying. B. Prepare the infant for surgery: This is the priority because pyloromyotomy is required to relieve the obstruction.

A. Administer oral rehydration solution: While rehydration is important, this is not the priority as the underlying cause must be corrected surgically.

C. Initiate a trial of thickened formula feedings: This is more appropriate for gastroesophageal reflux (GER), not pyloric stenosis.

D. Position the infant upright during and after feedings: While this helps manage GER, it does not address pyloric stenosis.

Question 2

A nurse is educating the parent of a child recently diagnosed with celiac disease. Which statement indicates the parent understands the teaching?

A. "I need to avoid giving my child rice and potatoes."

B. "My child can have wheat bread if it is toasted."

C. "I should read food labels carefully to avoid gluten-containing ingredients."

D. "This is a temporary condition, and my child will outgrow it."

Answer: C. "I should read food labels carefully to avoid gluten-containing ingredients."

Explanation: Celiac disease is a lifelong autoimmune disorder triggered by gluten (found in wheat, barley, rye, and oats). C. "I should read food labels carefully to avoid gluten-containing ingredients": Correct. Gluten is often hidden in processed foods, so label reading is essential.

A. "I need to avoid giving my child rice and potatoes": Rice and potatoes are naturally gluten-free and safe for children with celiac disease.

B. "My child can have wheat bread if it is toasted": Toasting does not remove gluten, so this statement is incorrect.

D. "This is a temporary condition, and my child will outgrow it": Incorrect. Celiac disease is lifelong and requires a strict gluten-free diet.

Question 3

A toddler with severe diarrhea is brought to the emergency department. The nurse notes dry mucous membranes, sunken fontanel, and delayed capillary refill. What is the priority nursing action?

A. Administer oral rehydration solution (ORS).

B. Offer clear liquids and monitor intake.

C. Start an IV for fluid replacement.

D. Provide a high-protein, high-calorie diet.

Answer: C. Start an IV for fluid replacement.

Explanation: The toddler shows signs of severe dehydration (dry mucous membranes, sunken fontanel, delayed capillary refill). B. Offer clear liquids and monitor intake: This may be part of supportive care but is not a priority in severe dehydration.

A. Administer oral rehydration solution (ORS): ORS is appropriate for mild to moderate dehydration but is not sufficient for severe dehydration.

C. Start an IV for fluid replacement: This is the priority intervention to rapidly restore intravascular volume and prevent shock.

D. Provide a high-protein, high-calorie diet: Nutritional support is important but secondary to fluid resuscitation in this scenario.